India: Rationing in disasters

Medical rationing sometimes seems inevitable during disasters. Major earthquakes, floods, and pandemics can leave health workers scrambling to care for all the patients who need attention—and can force some patients to go without.

But even in such dire circumstances, can rationing be avoided? An Indian doctor offers a hopeful tale.

The emergence of H1N1 or “swine” flu last year raised fears around the world of a severe pandemic.

In the United States, health officials planned for the worst. They were concerned that the number of patients needing artificial breathing support might far exceed the number of hospital ventilators available.

American health officials drafted emergency plans that set out which patients would, and would not, have access to life support.

Many of the plans included a chilling directive: patients who didn’t quickly improve could be taken off ventilators, most likely resulting in their deaths. That would make way for others who might have a better prognosis.

Thankfully the demand for ventilators during the pandemic did not outpace the supply in the United States. However, there was one place where it did.

The Indian city of Pune—not far from Mumbai—recorded that country’s first fatality from H1N1 flu in August 2009. The victim was a 14-year-old girl. Her death triggered widespread panic.

In and around Pune, more and more patients fell ill, but most hospitals wouldn’t accept them due to fear and government orders.

One of the very few places that would take swine flu patients was a state-run hospital called Sassoon General. It was quickly overwhelmed with patients.

Rationing seemed inevitable, but one doctor wouldn’t accept that.

An Influx of Patients

Dr. Aarti Kinikar lives with her family in a modest apartment, but she spends long hours at her job as a medical professor and head of pediatrics at Sassoon Hospital. She has short, no nonsense hair, and a quiet, often formal demeanor.

Kinikar recalled the month that the first patient died of H1N1. More than 100 seriously ill babies and children with flu symptoms such as fever, coughing, and difficulty breathing filled the pediatrics ward and intensive care unit. “We were not able to cope with this influx,” Kinikar said.

Sassoon is not one of the sleek, new Indian hospitals that attract medical tourists from wealthy countries. It caters mainly to the poor.

The intensive care unit for children has eight beds laid out side by side in an open room with tiled walls. There, the old and new India are juxtaposed. Doctors view x-rays and laboratory tests on computer screens just a few feet away from patients lying on moth-eaten mattresses under cobwebbed windows.

One of the patients who arrived struggling to breathe during the H1N1 panic was a ten-month-old boy named Ganesh. (His parents requested that only the family’s first names be used.) Ganesh tested positive for swine flu. His mother, Yogini, was terrified. “All we knew then was that when someone gets swine flu, the person dies,” she said through an interpreter.

In fact, the vast majority of patients with H1N1 flu recover without medical treatment, but Ganesh was critically ill. He couldn’t breathe on his own.

When Ganesh arrived at Sassoon by ambulance from another hospital, the pediatrics department already had more patients than it was equipped to handle. Kinikar said there were only two to three ventilators available for children with severe flu-like illness, “and then we had to decide which patients are going to go on that.”

If more than one child needed a ventilator and only one was available, the child with the best prognosis was chosen. Children who needed ventilators when none were available were ventilated manually by repeatedly squeezing an oxygen-filled bag connected to a tube in the child’s throat.

The outlook for them was often grim. “The best drug is oxygen,” Kinikar said, “and if you cannot deliver it in a proper way you are allowing the baby to be in your hospital but die in front of your eyes.”

Three of Kinikar’s patients died without ventilators the first week of the swine flu scare. The oldest was two and a half.

The Last Ventilator

Ganesh, the ten-month-old, arrived the following week. He was bluish and his heart was beginning to fail from a lack of oxygen. Ganesh’s mother, Yogini, believed God was testing her.

Yogini could see that the ICU was at its limit.

“All the beds there were full of patients, so it was pretty obvious there was only a small amount of machinery available,” Yogini recalled. “Seriously ill patients were coming in continuously.”

There was just one ventilator free. Ganesh was so sick his chances of survival looked poor at that moment, even with a ventilator.

Dr. Kinikar wanted to try. She put Ganesh on the last ventilator.

Some of the other doctors criticized this decision. Soon two more babies arrived who had difficulty breathing. Hospital policy forbids removing children with a poor prognosis from ventilators to make way for others.

Kinikar now found herself in the situation she had dreaded. There were no ventilators available for the two newly arrived children. “That’s how we started thinking, how can we at least give them the oxygen?”

Kinikar has a history of improvising when expensive medical resources are in short supply.

In the past, there had been times when the number of incubators for premature babies fell short, so she and her colleagues put their tiny patients in Styrofoam boxes to keep them warm. When the hospital where she was training didn’t have injectable caffeine to help premature babies breathe, she and her colleagues instead fed the babies instant Nescafe.

Kinikar has a mantra when she teaches. “God has given you the brain, just use it,” she says. “Just keep on thinking.”

Now it was time for Kinikar to think. Was there something she could do for the two babies who had just arrived? Could she improvise a way out of the shortage of ventilators?

A Risky Decision

Kinikar knew of another method to assist breathing. It’s usually used in newborns with premature lungs.

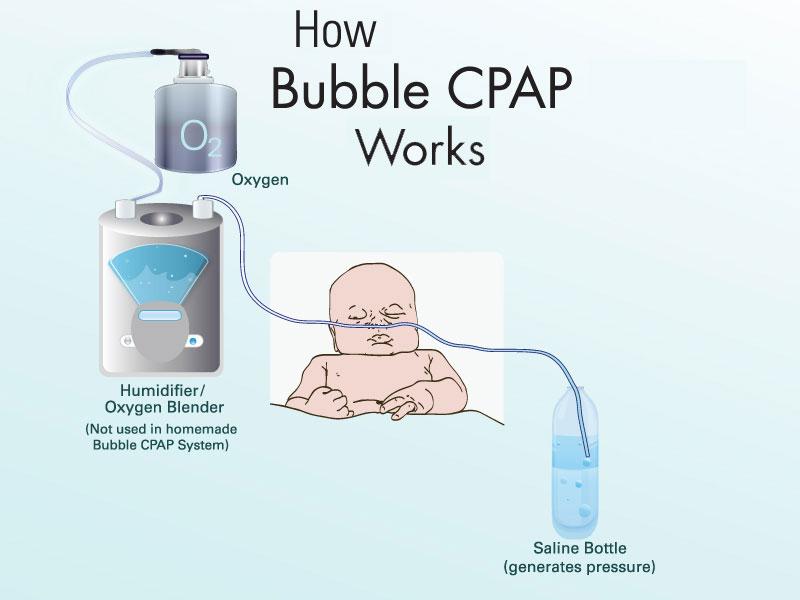

The infant breathes out into a nasal tube filled with pressurized air. The pressure helps prevent the lungs’ air sacs from collapsing when they’re poorly developed, damaged, or filled with fluid. The method is known as “bubble” CPAP, for continuous positive airway pressure.

The equipment costs around $10,000, but the mechanism is simple. Oxygen flows through tubing to the baby’s nose. The baby then exhales into tubing that’s submerged in a bottle of fluid. Like blowing into a straw, that creates bubbles and pressure—the deeper the tube, the higher the pressure.

Kinikar and her colleagues had patched together a homemade version of this device using a few dollars’ worth of plastic tubing and saline bottles readily available at the hospital. It seemed to work well on premature infants.

Now Kinikar wondered if she could use the same makeshift system to support older babies and young children with flu-related pneumonia. If the technique worked, it might decrease the need for ventilators—and therefore head off the need for rationing.

But a doctor’s duty is to “first do no harm,” and the improvised device lacked important safety features of the commercially available system. There was a chance it could make the children worse.

“It was like taking a risk,” Kinikar said. “I didn’t know whether people will back me using a technique which doesn’t seem to have much scientific push.”

The alternative seemed worse to her. “It was a decision between not doing anything and allowing the baby to die as against doing something and maybe keep your fingers crossed and let it work.”

The staff constructed bubble CPAP systems for the babies. Doctors connected nasal prongs to IV tubing and dunked the ends of the tubes into saline bottles.

Kinikar began treating the two babies who had arrived after Ganesh. When Ganesh showed signs of improvement on the ventilator, Kinikar decided to see if she could wean him off the machine early and instead support his breathing, too, with the improvised bubble CPAP system.

The tubing was connected to Ganesh’s nose. His mother, Yogini, watched warily.

“I asked, ‘What’s this new thing you’re putting him on?’” she recalled. She remembered being told, “This is bubble treatment.”

Yogini watched Ganesh slowly improve. “When I started feeding him and when he started smiling and rolling and playing around, then I thought I’d passed God’s test of faith,” she said.

A year later, Ganesh is a chubby, active child.

The two other babies treated in those early days of the pandemic also improved with bubble CPAP and never needed to be put on a ventilator. Over the course of the pandemic, hundreds of children were treated with bubble CPAP at Sassoon.

Lasting Effects

Other hospitals now accept flu patients and the pressure on Sassoon has lightened, but the improvised device is still heavily used in the Sassoon pediatric ICU. The doctors believe it has benefits for children even outside of an emergency.

On a recent day, a nine-month-old boy with large brown eyes lay on a bed in the ICU attached to the homemade assisted breathing system.

Oxygen bubbled through a humidifier bottle, then flowed down to the baby, then to a bottle of saline solution on the floor near the head of his bed. There, it bubbled again, creating the positive pressure.

The boy had arrived two days earlier with rapid, labored breathing and a positive H1N1 test result. With help from the makeshift device, he was already doing much better.

Kinikar said she sometimes thinks of the three children who died in those first days of the H1N1 pandemic and wishes she had improvised sooner. Now she teaches doctors at other hospitals how to use bubble CPAP. She calls her presentation “Bubbles of Hope.”

The system will still need to be tested more rigorously before its effectiveness is proven, but in Dr. Aarti Kinikar’s mind there’s no doubt that in the midst of a crisis, creative thinking and supplies that cost around $5 helped reduce the need for machines that cost thousands. They helped prevent her from having to choose who lives and who dies.

Kinikar sees lessons in her experience.

“You have to use your creativity,” she said, “and if you have the basic scientific knowledge, only the basic science, if that is clear, you will be able to do a lot of things with the gadgets which are available.”

The importance of maintaining flexibility in the face of a crisis could be useful for doctors in the United States, as well.

Many are fortunate to be able to offer their patients the latest, most expensive technology. A recent study showed that American hospitals have more ventilators per capita than most high-income countries.

In a severe pandemic or other disaster, however, the number of patients could easily overwhelm the supply of ventilators. Rationing might look necessary.

Dr. Kinikar’s experience points to another possible solution. As she’s fond of telling her students: “Just keep on thinking.”