In a post-Fukushima shift, Japan’s government charts a path back to a nuclear future

The government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is proposing to restore nuclear power to a prominent position in the country’s energy mix, nearly three years after a triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Japan will restart many of its nuclear power plants, but only after their safety has been established by the highest standards in the world.

That's the word this week from the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

It comes nearly three years after a massive tsunami caused a triple meltdown at Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

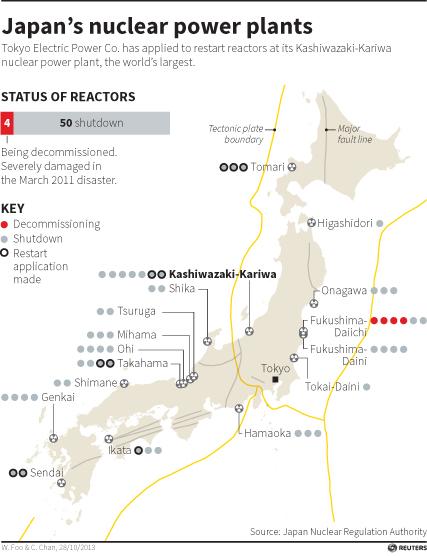

Nearly all of the country's 48 nuclear plants have been offline ever since. Successive governments have struggled to address the post-Fukushima energy crisis.

The country is still deeply divided over nuclear power so the government's new draft energy plan seems carefully crafted to avoid specifics. It says nuclear should be a primary, “base-load” energy source, but does not lay out a timetable for ramping the industry back up, nor exactly what percentage of the country’s electricity supply it should provide.

“And that's got to be a big question going forward,” says William Sposato, who covers energy issues in Japan as the Wall Street Journal's deputy Tokyo bureau chief.

Prior to Fukushima, nuclear provided roughly a third of Japan’s electricity with plans to increase that to half. Since the disaster the country has had to import huge amounts of fossil fuels to support its economy, still the third largest in the world but with almost no conventional energy sources of its own.

The question of how heavily Japan will again come to rely on nuclear depends on the rate of growth of new renewable technologies — which the draft energy plan maintains a commitment to developing — but also on the uncertain prospects of the country’s shuttered nuclear plants meeting new post-Fukushima safety standards.

“The rules are certainly getting much tougher, at least on paper,” Sposato says.

The country’s new Nuclear Regulation Authority, which was set up after the Fukushima disaster to replace an oversight agency widely seen to be too close to the industry, has vowed to be independent and to raise the safety bar, Sposato says.

“The head of the NRA has said that plants need to be ready for any eventuality,” he says, “not just the ones that they could likely expect to see,” like the kind of earthquake that set off the 2011 tsunami.

As for whether the new agency will remain truly independent of the government and the nuclear industry, Sposato says “that's an open question. Up 'til now, they've shown that they're willing to stand up to the government. At the same time, the government has been careful not to tread too hard” on the agency. “If they were seen to be riding roughshod over the nuclear regulator, that could cause a backlash for them.”

The policy shift back toward nuclear may be a bit of a surprise to people around the world who remember both the Japanese people and its government taking a sharp turn away from nuclear power after Fukushima. But Sposato says it’s not a surprise to the Japanese themselves.

“Abe has been pushing for nuclear power” since his election in 2012, he adds, despite public opinion polls that show “people are pretty much evenly split over whether the country should have any nuclear power generation at all.”

Sposato says strong anti-nuclear sentiment has been a political problem for the prime minister, but the anti-nuclear movement “hasn't really been able to coalesce.”

As one example, he points to the recent race for governor of Tokyo. While the office doesn’t hold any sway over national energy policy, Sposato says it became a referendum, of sorts, on the nuclear issue when one of the candidates, himself a former prime minister, ran on an anti-nuclear platform.

But Sposato says the candidate did poorly in the election, which may have helped embolden Prime Minister Abe to go ahead now with his new energy plan.

The plan does include continued development of renewable energy technologies like wind and solar, as promised by Abe’s predecessor after the 2011 disaster. And Sposato says there is also “some big money” for renewables coming out of the country’s private sector.

“But in practical terms,” he says, “energy experts say that when you add up the numbers, those sources are not really going to be able to make up for lack of nuclear power. So the only alternative for the country would be to continue to import very large amounts of fossil fuel, natural gas and oil.”

The draft energy plan still has to be approved by Abe’s government.