Albania’s Bunker Mentality

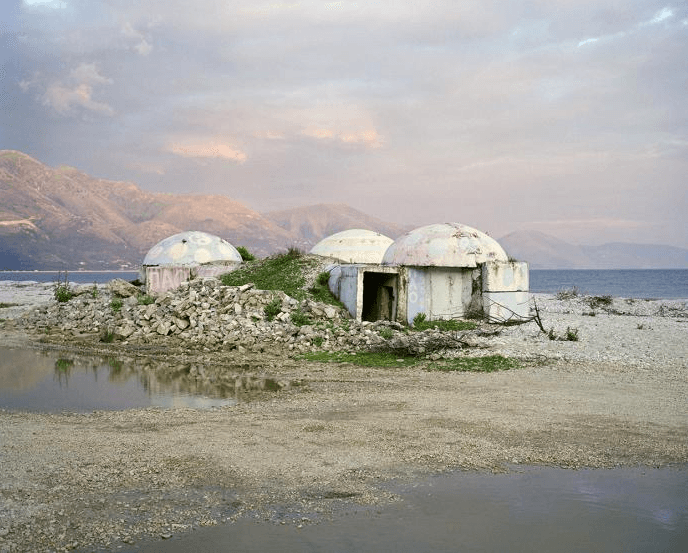

More than half a million concrete bunkers dot the Albanian landscape, holdovers from the Cold War. Now, Albanians are trying to figure out whether to reduce, reuse or recycle them. (Photo: David Galjaard)

You know the environmental mantra – reduce, reuse, recycle? Well, this story is kind of about all three.

Since the end of Communism, many of the bunkers have been re-purposed. But there are so many, Albanians don't know what to do with them all.

If you're looking for a poster boy that embodies "Communist strongman with an iron fist," Enver Hoxha's definitely your guy.

Let's tick the boxes.

Massive state security apparatus? Check.

Cult of personality? Check.

Rampant paranoia and xenophobia? Check and double check.

Here's a guy that not only feared attacks from the West, but also from fellow Communists like Tito, Khrushchev and later Mao.

And so in the late 1960s, Hoxha launched a concrete program to protect Albania from attack. He began constructing defensive bunkers. The final count? Somewhere between 750,000 to one million.

David Galjaard is a Dutch photographer who has been photographing these Albanian bunkers for the past few years.

"They are truly everywhere," Galjaard says. "You see them mostly close to the borders of course, but they are also inland. You'll find them in the most strangest places, like in the center of cities. You don't really expect them, but then they just pop out from a corner."

Galjaard traces the story of Albania's bunkers in a new book called Concresco.

He says that during Enver Hoxha's rule, some 80 percent of country's budget went to building them.

Galjaard notes that the bunkers came in three convenient sizes.

There were tiny, mushroom shaped ones which were barely big enough for two people. Then there were larger, mushroom-shaped ones, and finally there were big bunker complexes built into caves and rocks.

After communism fell, Galjaard says, the Albanians put them to use.

"People started to use the bunkers to live in, or build shops in, or grow mushrooms. And you still see that today. Most of them are used for hamburger stands, or cafeterias or little shops. But also the bigger round ones – one guy made a tattoo shop in it."

Most of the bunkers, though, sit empty and neglected.

And now, with the Cold War years receding, people are asking: what the heck should we do with them?

"Everyone has their own opinion," says Galjaard.

Call it a serious love/hate relationship.

Some military folks want to keep them as a reminder of the past. Others counter they should be wiped away…like all memories of the Hoxha regime.

And there's outside pressure as well. Chinese and Russian construction companies want the steel re-bar for new building projects.

Elton Caushi, for one, has fond memories of the bunkers.

"I was born and raised in the very center of the capital, Tirana," Caushi says. "We had the bunkers as well. They were quite a nice place to play hide and seek."

And as he and other Albanians grew older, Caushi says, they found other uses for the bunkers.

"In the Communist years in Albania, it was forbidden to have a girlfriend and to go in a hotel, or bring her home to have a bit of privacy," Caushi says. "So, where would the young couple go? Well, the perfect place was to go in a bunker."

The problem there, Caushi says, is that the bunkers were often used as public toilets.

Anyway – these days, Caushi helps run a travel agency called Albanian Trip. Many foreign tourists, he tells me, want to see the bunkers. In fact, they expressly ask to visit them.

But I don't think Albania's tourism board has quite caught onto that yet.

An official tourism video somehow manages to show five minutes of gorgeous footage from Albania. I couldn't see a single bunker, not even in the background. That is pretty impressive considering how many there are.

Elton Caushi is undaunted.

He makes the bunkers part of his itinerary for tourists, and he's helping a colleague try to finance the renovation of bunker complexes into little boutique hotels.

The first step, he admits, is cleaning them up a bit.