Love is blind: How Germany’s long romance with cars led to the nation’s biggest clean energy failure

Cars jam on the motorway A8 between Salzburg and Munich near Irschenberg, southern Germany, July 20, 2019.

A longer version of this story was originally published by InsideClimate News.

The night before the leaders of the European Union met in Brussels in 2013, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made a phone call.

After more than a year of talks, the EU nations had agreed on a plan to slash greenhouse gas emissions from cars and trucks.

But Merkel, the leader of the largest and most economically powerful of those countries, had a last-minute change of heart.

In a call to Ireland’s prime minister, Enda Kenny, the European Union president, Merkel persuaded him to delay a vote on the transportation issue. Using threats to close auto plants in other European nations and promises to cooperate on other issues, Germany then lobbied its way to a plan with more favorable terms for its auto industry.

“It was, for everybody, shocking,” said Rebecca Harms, a former member of the European Parliament from the Alliance 90/The Greens party, who was representing Germany in Brussels.

Germany’s transition to clean energy has had successes that can serve as models for other countries of how to combat climate change. But one of the most important lessons comes from a failure: The nation’s decades-long unwillingness to cut emissions from cars and trucks.

Related: What Germany’s energy revolution can teach the US

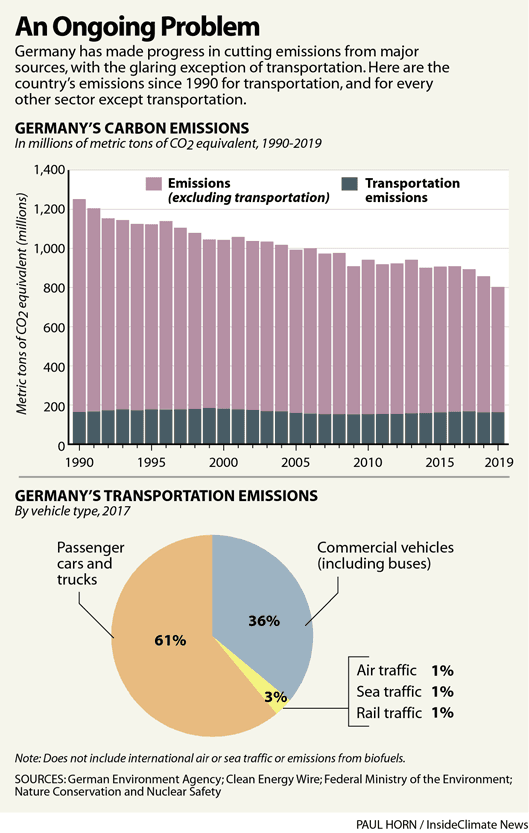

From 1990 to 2019, Germany made substantial progress in reducing emissions from electricity production. But Germans’ love affair with cars and the auto industry’s political clout meant that during the same period, the country made almost no headway in cutting the transportation sector’s emissions, which represent about one-fifth of total emissions.

The German government repeatedly deferred to the auto industry, wary of doing anything that might affect manufacturing jobs in the country’s No. 1 export and raise prices for consumers. Whether in national legislation or with the European Union, the government long acted as an advocate rather than a regulator of these corporate giants.

The result was dissonance: Germany nourished wind and solar power and democratized its electricity system through local cooperatives. At the same time, it was burning gasoline and diesel with abandon. The failure to cut vehicle emissions was severe enough to derail progress on meeting climate goals for the whole economy.

Last summer, I went to Germany to see where the energy transition stood now. I did not expect that I would spend so much time talking about cars.

I learned that the struggle to cut auto emissions is Germany’s great unsolved problem, and the process of addressing it is just beginning, a shift that is at once cultural, political and economic.

The United States faces its own long-term challenges in cutting transportation emissions, and can learn from the German example.

“The bigger lessons are really in the failure stories,” said Jonas Meckling, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of energy and environmental policy, who previously worked as a senior advisor for the German environment ministry.

One lesson, he said, is that an energy transition is not monolithic. It is made up of a series of challenges, and governments need strategies for each major sector of the economy. But even more important, he said, the leaders need to build and then maintain public support for making changes in each sector. And that gets complicated in a country where the love of cars runs deep, and speed is almost a religion.

In an energy transition, a (large) oversight

Germany began its Energiewende, or energy transition, in earnest in 2000, led by Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and a center-left coalition of Social Democrats and Alliance 90/The Greens.

The new leaders made rapid changes, but they were focused on the country’s largest emissions source, the electricity sector. The moves led to a boom in renewable energy and an ability for local communities to control projects and benefit from them. The transportation sector, however, was almost ignored.

In 2005, voters gave the center-right Chistian Democrats a plurality in the parliament, led by the new chancellor, Angela Merkel, who would turn out to be a staunch defender of the auto industry’s interests.

Over the next few years, a pattern emerged, in which Germany did little at the national level to deal with transportation emissions and also worked to weaken rules being considered by the European Union.

In 2007, the European Union enacted its first mandatory emissions rules for vehicles, a plan that would have been more stringent if Merkel’s government had not successfully pushed to set the standards at a level amenable to Germany’s auto industry.

Those standards took effect in 2009, in the middle of a global economic downturn. Environmental advocates were pleased to see early evidence that mandatory rules seemed to be working in a way that voluntary rules had not.

And they were eager to get back to the table to update the rules and make them more stringent, a process that came to a head in 2013.

The deal they reached was a fair compromise, she said, with rules that were not as tough as environmental groups would have liked, but clearly a step in the right direction.

Then, out of nowhere, Merkel intervened. She phoned various heads of state to ask them to join her in pushing to reopen the negotiations.

Saar learned of the sudden change of plans from a newspaper.

“What a mess,” she said, remembering her reaction.

Merkel’s actions had short-circuited the regular process of EU law making. Reopening the negotiations, however, only led to minor changes to the agreement. Six months later, the sides agreed on a plan to impose tougher emissions rules by 2021 instead of 2020, with new provisions that would give automakers credit for electric vehicles that would count toward offsetting emissions for other models.

Harms, the former European Parliament member, now thinks Merkel’s actions affected the credibility of the process in a way that ended up doing much more damage than the changes to the policy.

In response to questions from InsideClimate News about Merkel’s role in the 2013 negotiations and the criticism that she has been too close to the auto industry, a spokesman for the Merkel government said the chancellor “maintains working relationships to all major sectors of the German economy.” He added that the EU rules for carbon emissions from vehicles, including those passed since 2013, set a “global benchmark.”

That Germany was a leader in supporting renewable energy but also an adversary of dealing with transportation emissions might seem contradictory. Yet, inside the country, it made sense.

“Our economy still is dominated by the mobility sector, mainly by the German automotive industry and the suppliers,” said Christian Hochfeld, director of Agora Verkehrswende, a Berlin think tank that focuses on clean transportation policy.

Transportation emissions, he said, are “the elephant in the room” when it comes to Germany seriously addressing climate change.

Auto manufacturers, including parts suppliers, employ more than 800,000 Germans, making the industry an economic powerhouse. Those numbers alone would be enough to wield political influence. But the industry also has plants in nearly every German state, giving it local and national power.

In 2015, though, this bedrock industry was about to squander its goodwill.

Deconstructing ‘Dieselgate’

The German government’s efforts to protect the auto industry included staying out of the way of the growth strategy of its largest automaker, Volkswagen.

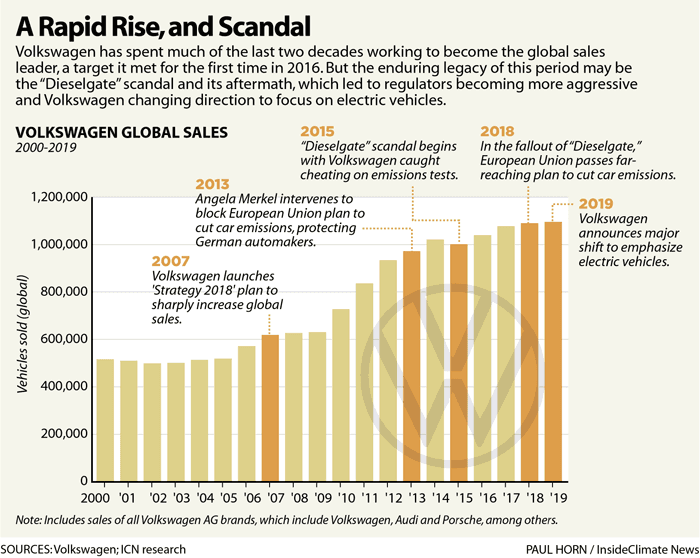

In 2015, Volkswagen was eight years into a corporate plan to increase its annual sales from the 6.2 million vehicles it sold in 2007 to 10 million vehicles, a number likely to make the company the world’s leading automaker.

Volkswagen aimed to grow in the United States by competing in the SUV segment, and by marketing its diesel vehicles as good for the environment. The catchphrase for the company was “clean diesel.”

While it was true that Volkswagen’s diesel engines were fuel efficient, with low carbon dioxide emissions, diesel vehicles emitted high levels of nitrogen oxide, a major contributor to air pollution.

To sell diesels in the United States and meet air quality regulations, Volkswagen needed to install equipment to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions. But this equipment also harmed the vehicles’ performance, making the cars feel sluggish when they were driven.

So the company cheated. Its engineers developed software that could detect when a car was driving onto a lab platform for emissions testing and would then engage pollution controls. On the open road, however, the vehicles spewed nitrogen oxide at levels up to 40 times legal limits.

The scheme might have gone undetected if not for a small group of researchers from West Virginia University that did tests of various brands and vehicles to see how emissions in the lab compared to emissions on the road. After several tests, it was clear something was amiss with the Volkswagen cars.

Volkswagen initially deflected, then blustered, accusing the testers of making mistakes. But the company had been caught, and the evidence continued to accumulate, exposing wrongdoing by other automakers, as well.

Merkel urged Volkswagen and other companies to fully disclose what they had done.

“I am just as disgusted with this deception as you are, with this cheating of customers,” Merkel said in a 2017 interview.

Longtime observers of German politics and business could see signs that the government and the auto industry were no longer in lockstep, setting the stage for another round of European Union talks about increasing vehicle emissions standards in 2018.

The negotiations did not play out as they had before. Other countries pushed harder for aggressive action, and were less deferential to Germany. The result was a compromise, but one that went further than ever before.

Under the new rules, adopted in December 2018, countries are required to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from new cars by 15 percent by 2025 and 37.5 percent by 2030, compared to a 2021 baseline.

A change of heart

Volkswagen soon demonstrated that it was ahead of its government in recognizing that the future of the auto industry lay in electric vehicles (EV).

Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess rolled out a new strategy in March 2019, announcing an increase in the number of planned EV models and a new goal of selling 22 million EVs in the next 10 years, up from the previous goal of 15 million in the same period.

“Volkswagen will change fundamentally,” Diess said at a news conference at the company’s headquarters. “Some of you may still be rubbing your eyes in amazement, but there’s no question this supertanker is picking up speed.”

Germany’s other leading automakers, Daimler and BMW, also were increasing their emphasis on EVs. With the automakers moving in this direction, the German government was running out of reasons not to pursue national legislation to reduce vehicle emissions.

In December, Merkel’s governing coalition passed legislation designed to accelerate the country’s progress in cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Among its many provisions, the law included Germany’s first-ever carbon tax for transportation, which will increase the cost of motor fuels such as gasoline and diesel when it takes effect next year.

Breaking the chains

As bad as the Volkswagen scandal was, it may ultimately have saved the company and, by helping to enact more aggressive vehicle emissions rules, provided much-needed momentum for the German energy transition.

Hochfeld, director of Agora Verkehrswende, the Berlin think tank, added, “The diesel scandal broke a lot of chains between the policymakers and the car industry and it also broke a lot of chains between German people and the car industry, because they lost their trust and they lost their pride in this industry.”

Even Volkswagen can see that the scandal has led to positive changes.

“The diesel crisis, the scandal, was a loud and clear call for action,” said Ralf Pfitzner, Volkswagen’s head of sustainability, in a phone interview. “It’s now helped us to be at the forefront of electrification.”

Environmental advocates are cautiously hopeful that this change is enduring, part of a broader shift that could turn around what has been the greatest failure of the country’s energy transition.