What Germany’s energy revolution can teach the US

A longer version of this story was originally published by InsideClimate News.

Twenty years ago, before climate change was as widely seen as the existential threat it is today, Germany embarked on an ambitious program to transform the way it produced electric power.

Over the next two decades, it became a model for countries around the world, showing how renewable energy could replace fossil fuels in a way that drew wide public buy-in by passing on the benefits — and much of the control — to local communities.

The steps Germany took on this journey, and the missteps it made along the way, provide critical lessons for other countries seeking to fight climate change.

Last summer, I went to Germany to figure out where the energy transition, or “Energiewende,” stands today, with climate change blaring like a siren across a nation already alarmed. Record-breaking heat in successive summers had left the fabled German forests dotted with clumps of dead brown trees. My hotel room in Berlin was broiling.

Related: Decades of science denial related to climate change has led to denial of the coronavirus pandemic

As a longtime energy reporter, my working hypothesis was that Germany’s experience held many lessons for the United States.

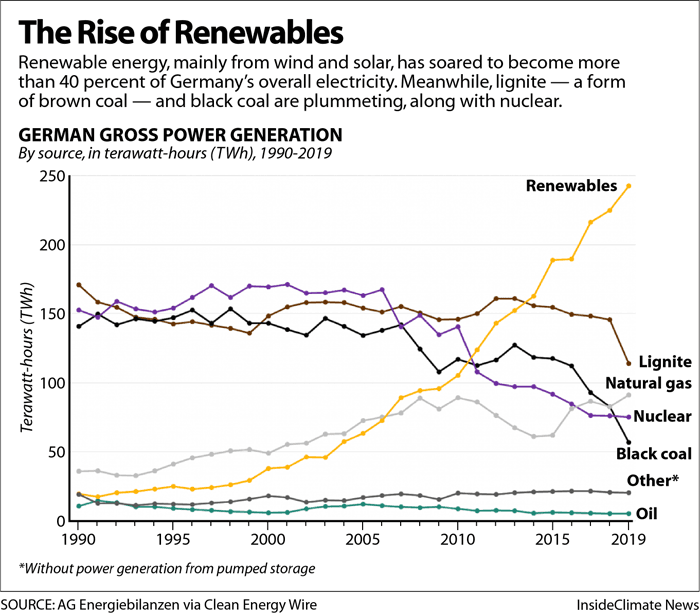

While Germany has made immense progress on climate and clean energy, the United States has lagged far behind. Germany now generates 43% of its electricity from renewable sources, compared with 17.5% in the United States.

“What Germany did has made a huge difference for everybody, for the whole world.”

“What Germany did has made a huge difference for everybody, for the whole world,” and the United States should pay attention to that, said Greg Nemet, a University of Wisconsin public affairs professor who has spent years studying German energy policy.

Yet Germany’s energy transition was hardly a straight-line journey of success.

Hope, disillusionment, then hope renewed

It was a time of far-reaching optimism and ambition in 1998, when German voters thrust a center-left coalition into power. The new government aimed to dramatically increase renewable energy while phasing out nuclear power.

Two years later, lawmakers passed landmark legislation that provided the financial incentives for the coming boom in wind, solar and other renewable energy. The 2000 law was in many ways the starting point for the intense period of progress that followed.

“We thought we could change everything,” said Eveline Lemke, a member of Alliance 90/The Greens, the coalition partner that made clean energy a centerpiece of national policy.

The new policies transformed the energy economy, making it cleaner and less centralized. Solar panels popped up on roofs and giant wind turbines sprouted across the countryside.

But the growth wasn’t sustained. By 2014, the steep cost of renewable energy subsidies produced high electric bills and a conservative backlash. Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose center-right government was first elected in 2005, responded by making changes to clean energy laws that slowed development.

The momentum faded into disappointment for many Germans. One of the big problems was that emissions from vehicles were essentially flat. This meant that Germany was on track to miss its emissions-cutting target for 2020, which was to reduce emissions 40% from 1990 levels.

But last year, spurred by mounting protests and calls for more aggressive climate action, Merkel’s government took a series of steps to assert the country’s commitment to move away from fossil fuels.

The German Parliament passed a $60 billion proposal that would, for the first time, impose a tax on nearly all carbon dioxide emissions. It also provided additional subsidies for wind and solar energy, and accelerated the push to cut emissions from automobiles, trucks and airplanes. The parliament also adopted a plan to shut down all coal-fired power plants by 2038 and provide $45 billion to help coal miners and their communities through the changes.

Yet environmental activists are quick to note that the new momentum did not originate in the halls of parliament. It came from the cities and villages, and from the massive Fridays for Future demonstrations inspired by Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenage climate activist — a bubbling up of grassroots enthusiasm that has given renewed hope to many people who were at the heart of the early-2000s push for renewable energy.

That new hope was what I had come to Germany to see.

A scorching summer

One of the first things I noticed in Berlin was the heat. My hotel and most of the offices I visited did not have air conditioning, having been built at a time when cooling was rarely needed in this northern city.

Scientists say it’s not possible to attribute a single heatwave or unusually hot summer to climate change. But the long-term trend is clear: Berlin and indeed, all of Germany are getting hotter, as is the world.

Related: Earth’s hottest decade on record marked by extreme storms, deadly wildfires

And that feels particularly dire for people whose work is tied to the energy transition.

One of those people is Karsten Neuhoff, head of climate policy for the German Institute for Economic Research. On my second day in Berlin, I went to his austere office building, located near Checkpoint Charlie, a former border checkpoint from when Berlin was a divided city during the Cold War.

For me, this was much more than an ordinary interview with a policy expert.

I grew up in Norwalk, Iowa, a small city near Des Moines. When I was a freshman in high school in the 1990s, an exchange student from Germany lived with a host family across the street from my parents’ house. He and I were in band and speech classes together. He was funny and friendly, with an exceptionally wavy head of hair. His name was Karsten Neuhoff.

As I was preparing to travel last summer, I asked researchers in the United States to recommend German experts I should interview. One of the names they gave me was Karsten Neuhoff.

I assumed there was no way that this energy economist could be the same person who was in marching band with me. Then I saw his photo. It was.

When we met in Berlin, I saw that his warmth and smile were just as I remembered, but his head of hair was sadly lost to time.

He told me about his vivid memories of how his host family in our town felt pride that Iowa farmers provide corn for the world, and how this would later inform the way he viewed Germany’s transition to clean energy.

The key, he said, is for people to have some control over renewable energy development and to directly benefit from it, as opposed to having the development imposed on them.

He added, “Citizens must have confidence in the ultimate goals of the system: Why are we doing this?”

A village finds a new income source: Renewable energy

To see what a decentralized energy system looked like up close, I made the daylong journey by train to Wildpoldsried, a village of about 2,600 residents that produces about eight times more energy than it consumes, and sells the surplus back to the grid.

“I always try to tell people that we are a totally normal village, but nobody believes me.”

“I always try to tell people that we are a totally normal village, but nobody believes me,” said Günter Mögele, a high school teacher who has served as deputy mayor since the late-1990s.

Renewable energy can be seen from almost every vantage point in the village, with solar panels fastened to clay-tile roofs and wind turbines in the distance.

What I found most remarkable about Wildpoldsried wasn’t how extensively renewable energy was relied on, but what leaders chose to do with the financial proceeds. By selling electricity to the grid, the village gave itself a new income source and improved the lives of residents, offsetting most of the costs for preschool, child care, sports and community theater.

Many other communities have their own version of Wildpoldsried’s energy accomplishments and have used money from wind turbines and solar arrays to improve services and lower taxes.

In a battle over cost, Merkel’s conservatism wins out

But the momentum of the early years of the Energiewende didn’t last. Merkel and her government began to change the formula that had led to the rapid growth of renewable energy.

Merkel agreed with the country’s broad consensus that carbon emissions must be drastically reduced. But she wanted to do it in a way that was mindful of costs.

It wasn’t hard to make the case that the costs were too high, considering that the renewable energy surcharge had more than tripled from 2010 to 2014. For a small household, the cost had risen to about 20 euros — or $22 per month.

By 2014, the government had agreed to overhaul renewable energy policy, a change that took several years to implement. Instead of being open to almost everyone, groups that wanted to create renewable energy projects and sell the power to the grid needed to compete in auctions to see who could offer the lowest price.

Related: On Baffin Island in the fragile Canadian Arctic, an iron ore mine spews black carbon

Solar and wind power continued to grow, but the new rules meant that small players had a much more difficult time. The energy transition was becoming the realm of big developers.

Now Mögele and many other local leaders are calling for the government to overhaul the rules once again, making it easier for small local energy producers. Wildpoldsried had already done enough to secure its financial stability, he said, but he could see how those opportunities were vanishing for others.

“It will change. It has to change,” he said.

A teenage protester helps revitalize a movement

There is no clear point at which the Energiewende began its revitalization, but one of the central factors was the arrival on the scene of Greta Thunberg, a 15-year-old in Sweden, who skipped school to stage a one-person demonstration outside her country’s parliament building in 2018 to call attention to the failure of leaders to address climate change.

Thunberg’s message and ongoing activism gripped much of the world, and had a particularly strong effect in Germany.

Merkel’s government has seen the rise in public interest in climate change and has taken steps to address some of the most vexing challenges in the energy transition. But Merkel is also on her way out, planning to step down ahead of the next election.

And yet, there are vital ingredients still missing. Critics of the government’s recent actions say more needs to be done to reinvigorate the small, local projects that were so important to creating the sense of shared benefits in the early days of the energy transition.

But many here say it’s the first step in a process, a signal that the country has a renewed focus.

An unexpected crisis and a warning for the future

Earlier this month, I called Karsten Neuhoff on Skype. Our countries were several weeks into coronavirus lockdowns.

I wanted to know how the global crisis had affected the trajectory of German climate policy, and to see how he was coping with the pandemic.

“Sometimes doomsday scenarios can happen.”

“It demonstrates that sometimes doomsday scenarios can happen,” he said, speaking from his kitchen table, late in the evening. “The idea of viruses that spread globally were the stuff of TV movies, and suddenly it became reality.”

He added that he thought this had implications for climate policy, because the public might now have a deeper understanding of the economic disruption that is possible if climate change is unchecked.

Related: Exxon and oil sands go on trial in New York climate fraud case

We agreed, though, that the crisis could also have detrimental effects on climate policy, with the sudden drop in emissions caused by the economic fallout potentially giving cover to backslide on climate. Indeed, a recent forecast shows Germany is now likely to reach its emissions-cutting target for 2020, a goal that previously seemed out of reach.

What about the big takeaway from my time in Germany, the idea that the success of the energy transition is closely tied to whether the public is engaged and feels like it has a stake?

That hasn’t changed a bit, Neuhoff said. The virus, and people’s response to it, has demonstrated that we’re all in this together, a sentiment repeated often in recent weeks, both in Germany and in the United States.

Neuhoff said he is hopeful that the US government and the public will embrace this idea as it applies to climate change. If and when that happens, Germany has two decades worth of trial and error to show how this can be done.