The Mexican government says it will help people who are deported, but they often are left to make it on their own

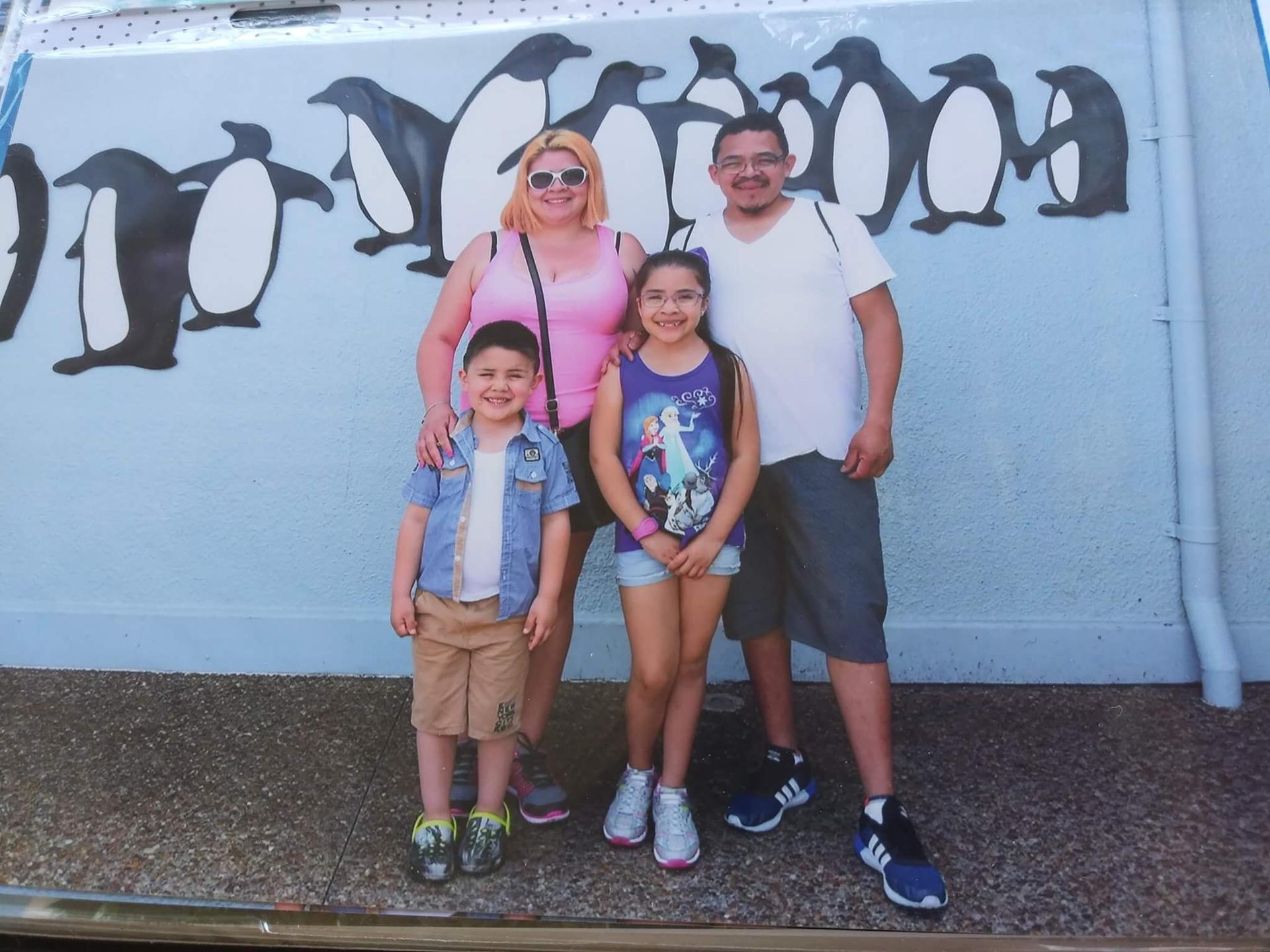

Omar Blas Olvera visited Sea World, in Florida, with his wife Gloria and children, Esperanza and Angel, in May, 2017. The family lives separately for now, since Omar was deported from the US to Mexico in July, 2017.

Halfway through the flight, the officers took off Omar Blas Olvera’s handcuffs. He asked why. They had entered Mexican territory, an immigration agent told him. It was July 26, 2017. After they landed in Mexico City, he looked out the window and saw the airport’s signs in Spanish.

Just a few months earlier, Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto welcomed 135 deported men and women at Mexico City’s airport. He touted Somos Mexicanos (We Are Mexican), a federal program to help repatriated nationals.

“You’re not alone. Don’t feel abandoned. The doors to this house will always be open,” Peña Nieto said then.

So when Blas arrived, at 30 years old, he had hope for starting a new life with his family in Mexico.

“When I got off the plane, I would have liked for someone to tell me, ‘We’re going to help you in any way we can, for you and your family to get together,’” he says.

It didn’t quite go the way he thought it would. There was someone from Somos Mexicanos at the airport to welcome him, but he was put into a system that was confusing to navigate and left him feeling helpless.

Blas lives now in his hometown of San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, in central Mexico. Mexico’s interior ministry reports that 166,986 Mexicans were repatriated from the US in 2017, the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Under Somos Mexicanos, Mexicans who are repatriated have a point of contact with federal immigration authorities who accompany them as they seek services from state or municipal programs, or the private sector. What support is available depends mostly on local budgets as well as on how much interest there is to help deported people in each place, says Dalia García Acoltzi, director of the Somos Mexicanos program at the National Migration Institute (INM), Mexico’s federal immigration agency. “Each state is completely different,” she says.

José Gerardo Morales Moncada, secretary of social and human development for the state of Guanajuato, says the help they offer is like a “tailor-made suit,” different for each person. Their program is called Guanajuato Sin Fronteras, or Guanajuato Without Borders.

Morales Moncada points to the case of Guadalupe García de Rayos, who was deported from Arizona in February 2017. García de Rayos, the mother of two US-citizen teenagers, was arrested in 2008 by deputies of the controversial former sheriff Joe Arpaio. She was charged with working with false documents at a waterpark.

In Mexico, consular officials were waiting at the Nogales border crossing to assist her. They traveled with her to Acámbaro, Guanajuato, her hometown, García de Rayos says. Her story made international headlines as one of the first deportations in the Trump era.

“We looked for her,” says Pauliette Morales, a spokesperson for the State Institute for Attention to the Guanajuato Migrant and Family, which runs Guanajuato Sin Fronteras. The agency often seeks out people whose deportations are covered in the media, she says.

But Blas’s detention on July 8, 2017, wasn’t in the news. It happened quietly. He was pulled over in the morning by an unmarked Ford Expedition while he was driving out of the trailer park where he lived in Sterling Heights, Michigan.

An Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent asked him for ID; Blas showed his expired Michigan driver’s license and the agent took him into custody. Blas had heard in social media about immigration raids in the area, so the arrest didn’t take him completely by surprise.

He asked the agent to let him go back home to say goodbye to his family. The agent said no.

ICE says Blas’ arrest was part of a “targeted enforcement action” in which they were specifically looking for him.

“He has previous misdemeanor convictions. ICE focuses its enforcement resources on individuals who pose a threat to national security, public safety and border security, “ spokesperson Khaalid Walls told PRI in an email.

The arrest led to Blas’ third deportation from the US, and a decade ago he was convicted for driving under the influence of alcohol. Blas came to the US alone when he was 15 years old, to join an uncle, go to school and work.

Deportations of people like Blas and García de Rayos, both of whom came to the US as minors and have US-born children, have been happening since before Trump took office.

But the Trump administration has expanded its priorities to people who have any type of criminal record, and is pursuing prison time for those with illegal re-entries. Blas thought this time it would be better if he stayed in Mexico rather than risk being separated from his family again.

“I can spend money and I can have someone take me [to the US], but in a few months a cop will profile me and it will be the same thing all over. It’s not worth it,” he says.

But settling in Mexico wouldn’t be easy. He needed a plan to bring his wife, 10-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son — all US citizens — to Mexico.

Also: Her husband is being deported. So, this US native is moving with her two children to Mexico, too.

He also had to take care of the debt he left behind, not just credit cards for Victoria’s Secret and Home Depot, but the loan they took to buy a $30,000 car.

“For as long as I was working we were OK,” Blas says. In Michigan, he was a contractor. He became an expert on tile work, which he did with his uncle since he was 17. In his last two years in the US, he started taking on his own projects, especially with marble and granite, and including government buildings.

“I was making good money, and I wanted to give my family some good living, some things they didn’t have,” he says.

When Blas reached San Miguel de Allende, his first task was to afford rent for home for his family. In the meantime, he stayed at his parents’ house and shared a room with his nephews.

García De Rayos moved back with her parents in Acámbaro at 36 years old, after 21 years of living in the US.

“It was tough,” she says. Her two children and husband had to stay in the US. But in Mexico, she got more support than she expected.

In about two months, she opened a tortilla stand, “Tortillería Lupita,” with training and 320,000 pesos ($17,000) in funds given by the state. She started to earn about 450 pesos, ($23), a day. Municipal officials helped García De Rayos get her Mexican ID and the state helped pay for her children to fly to see her several times

Blas’ experience was different. At the Mexico City airport, Blas was given a constancia de repatriación, proof of repatriation — a sheet of paper with a blurry picture of him and an identification number that could serve as a temporary form of ID.

Even though his hometown was in San Miguel de Allende, immigration officers directed him 76 miles from there to the Guanajuato state capital, León. Blas wasn’t looking for a handout; he just wanted to get back on his feet as soon as possible. He says the officers told him that in León he could get help with bills and finding work.

But Blas found no help at the office in the state capital. So he returned to his hometown, where he was bounced between federal government offices and municipal buildings several times over the next month. He kept little scraps of paper with the names of the people he was referred to, handouts about city services, and long lists of requirements. In each phone call and visit, he was trying to access services — but often got the same answer: He was in the wrong place.

Finally, he found a program for people who were deported, run by the city of San Miguel, that could lend him up to 60,000 pesos (about $3,200)to buy tools and start his own business. But he had to put 20 percent down. He had come to Mexico with nothing and couldn’t afford to take out the loan. Without his income, his family in the US couldn’t afford to send him money, either.

“This is the only program I have and they’re already cutting it down,” an official at the city told him.

Another one of the requirements of the loan program was an official voter ID, known as IFE. To get IFE, he needed his birth certificate. To get his birth certificate, Blas had to take his brother and mother to a local office to confirm his identity.

“It’s like they make it impossible to get help from the government,” Blas says. “I think about other people that don’t have anyone here. I don’t know how they would manage.”

Blas wanted to bring his family to Mexico, and he wasn’t going to wait for government programs to kick in to do it. So by the first week of August he found a job as a busboy at a local restaurant through someone he met in 2010, when he was deported before.

He kept trying to get a loan, though. At the end of August, he returned to the city office with his IFE and a quote from a hardware store for all the tools he needed to start a tiling business. He had to present at least two copies of every document. They put him on a waiting list and he never heard back.

San Miguel de Allende was the first city in Mexico to sign an agreement with Somos Mexicanos to provide services to those repatriated. Mayor Gonzalo González says they had 400 jobs available in the private and public sectors in April 2017 that people who have been deported could apply for.

“We do everything we can in San Miguel so when they return they can have a job,” he says. The number of positions overall have increased in the tourist enclave by 12.3 percent annually over the last three years, compared to 3.9 percent in the rest of the country, says González. In 2017, about 60 people of those who were repatriated from the US each month returned to San Miguel, according to the state immigration institute. González thinks they will “sadly” increase.

“Sadly, because that means that families will be torn apart,” he says.

In 2017, the city helped 64 repatriated people with 1.5 million pesos (about $80,000) dispersed mostly in the form of no-interest loans. This year, they’ve supported 35 requests for help with close to about 835,000 pesos, (over $43,000).

Blas tried to get some of that start-up money. The mayor regrets Blas didn’t receive help. But local activists say that it’s not just Blas; they say many people who have been deported are not receiving the help that Mexico federal government has promised.

In 2017, Guanajuato received over $2.5 billion in remittances, mostly from people who were living in the US. Mexico as a whole received $28.8 billion in remittances according to Mexico’s central bank.

Yet not everyone believes those contributions are appreciated once Mexicans abroad are deported.

“There’s no support and they feel discouraged,” says pastor Ignacio Martínez, who runs the ABBA shelter in Celaya, Guanajuato, 40 miles from San Miguel de Allende.

Martínez is part of Caminamos Juntos (We Walk Together), a newly formed effort in San Miguel to fill in the gaps of support for those deported to Mexico, especially when they come back with their families. The volunteer group helps people who are deported get Mexican documentation, jobs and housing, as well as offering moral support and mental health services to cope with the trauma of being uprooted.

Martínez is used to working with Central Americans who are fleeing violence in their homelands. For some of them, arriving in Mexico could be a relief, he says.

But for those who are deported to Mexico from the US, it can be a “devastating” experience.

“They’re coming from 16 to 30 years of living there, sometimes only with the clothes on their back,” he says. “This is a crisis at the social level. On the one hand, the rejection of a country that doesn’t want them. On the other hand, a country that receives them and doesn’t know how to help, because it doesn’t have the capacity.”

For Blas, things took an unexpected, but positive, turn.

In October, Blas’ wife Gloria was able to sell their truck in the US for $9,800 and their trailer home for $3,500 (paid in installments by the buyer). He and his wife used that money to pay for passports, his daughter’s orthodontics treatment and plane tickets for the family to reunite in San Miguel.

Katerina Barron had also moved to San Miguel when her husband was deported. She became a volunteer for Caminamos Juntos and collected donations to help furnish the Blas’ apartment. But when the children arrived, Gloria realized they could not enroll them in public school because classes had already begun. Private schools were too expensive and they tried homeschooling, but it didn’t work.

Blas’ wife told him, “We don’t like to be away from you, but we need to look after the education of our children.” He didn’t like the idea, but knew she was right. In January, about three months after they arrived, Blas’ family returned to the US without him and stayed with family members there.

They plan to return when this school year ends. In the meantime, Blas hasn’t gone back to tiling.

By February, after seven months of working as a busboy at the local rooftop bar Quince, Blas become a quality manager for the restaurant making about 80 pesos an hour (about $4) and by the end of April he was named the chief operations officer with an upcoming raise.

“I was never asking for anything for free,” he says. “I know that it’s not everybody’s problem and that I was there [in the US] without papers and all, but I wish that the [Mexican] government would stand up for us.”

This story was produced with the support of the Adelante fellowship from the International Women Media Foundation.