Stuart Banks was inside the submersible Alvin as it descended to the ocean floor when the discovery was made.

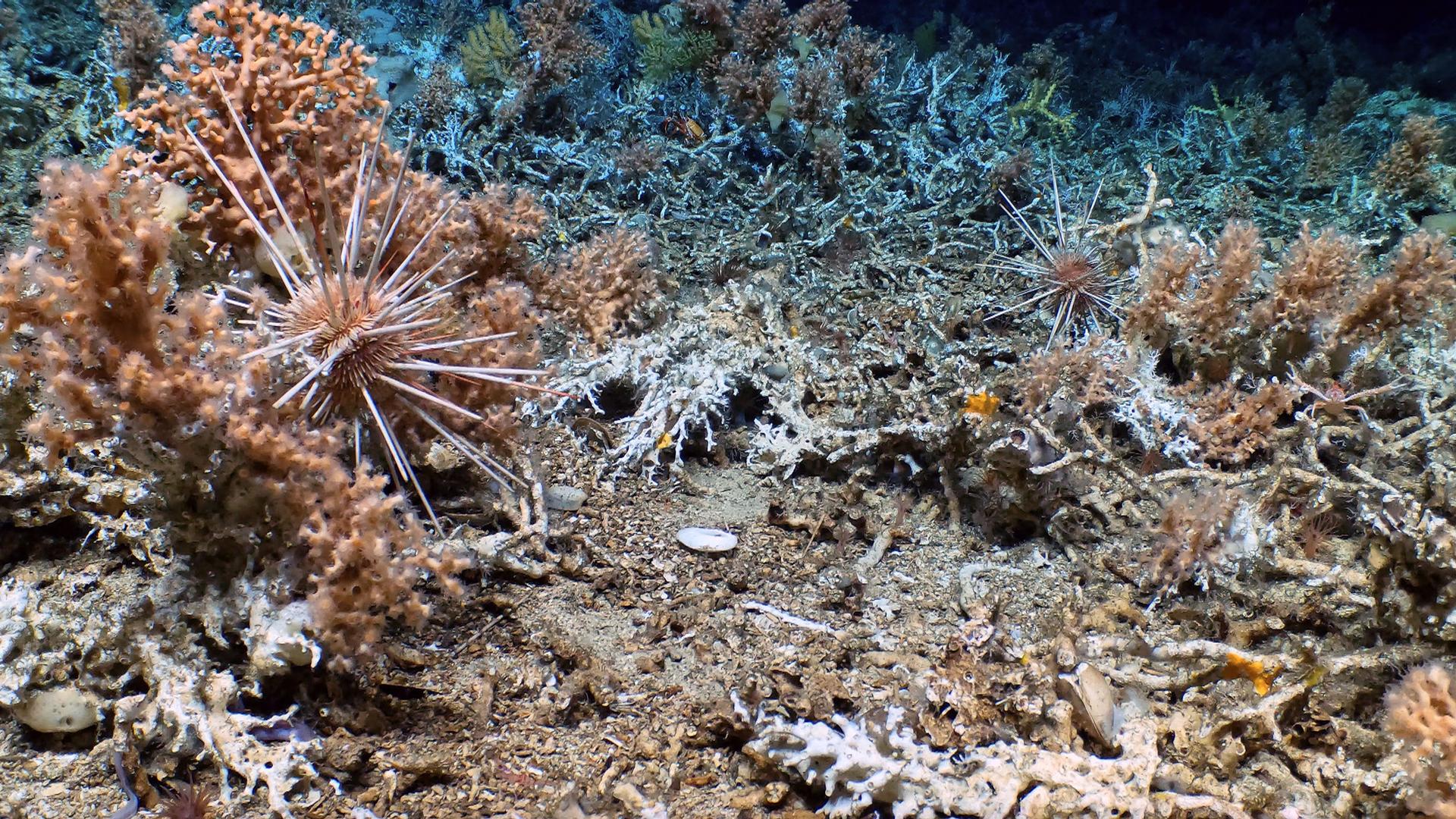

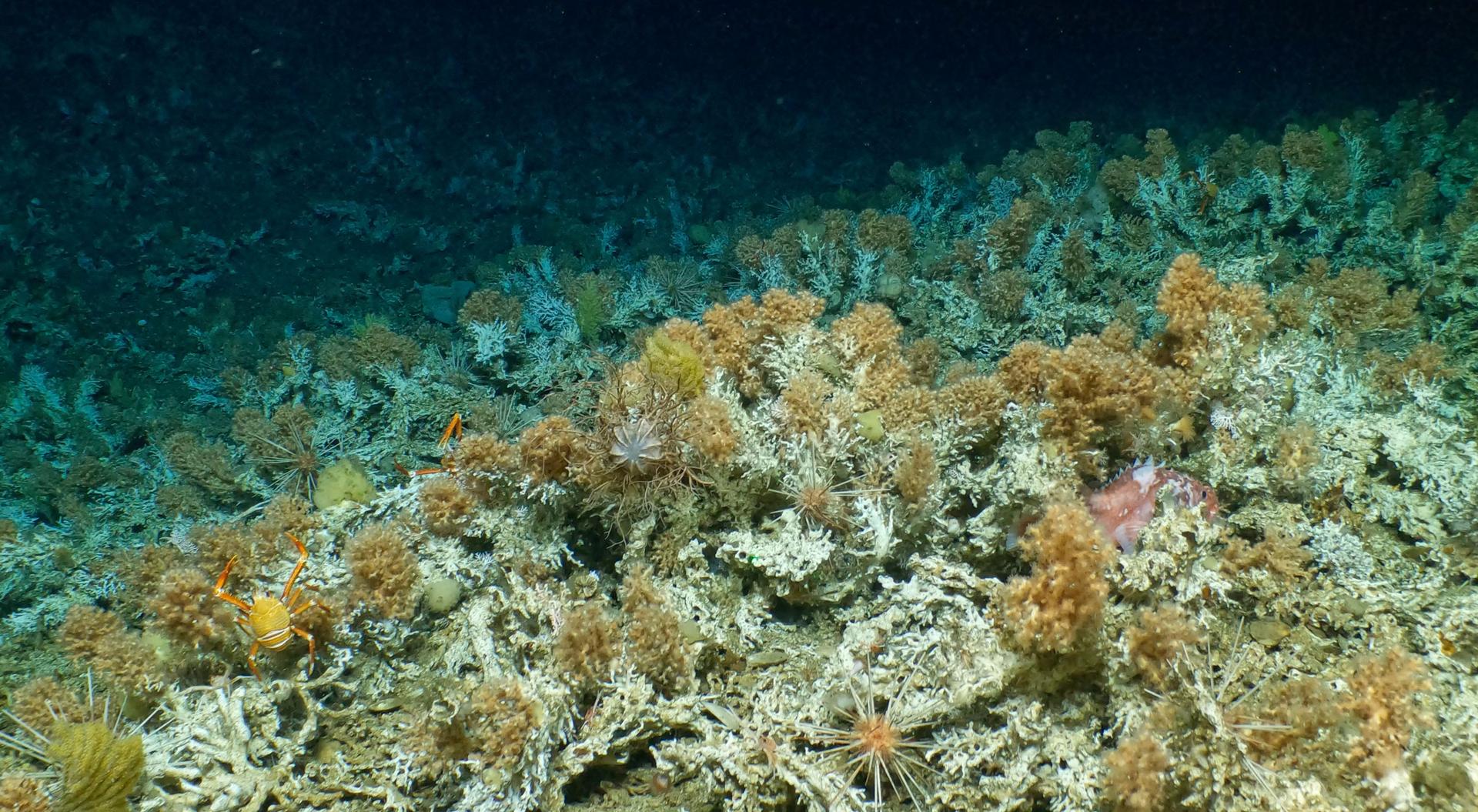

“Suddenly, there was this huge built-up reef that just went on and on and on,” said Banks, a senior marine scientist at the Charles Darwin Foundation.

He was one of two scientists and a pilot who were aboard the Atlantis deep-water research expedition submersible when they unexpectedly discovered these deep-sea coral reefs off Galapagos earlier this year.

Once the shock and awe of the discovery subsided, the scientists went to work.

They used the submersible’s external mechanical arms, nets and a vacuum-like device to collect samples.

It was like striking gold for Banks and the other scientists on the expedition. The reef, Banks said, “was a highly productive, ancient, extremely physically vulnerable, unmapped habitat.”

A few months later, Banks showed off some of the coral samples in a lab room at the Darwin Foundation on Santa Cruz Island in the Galapagos.

Corals are laid out on the counter — spiny fossils in plastic bags and live specimens, orange and purple, floating in alcohol-filled jars.

“This is a fossil coral,” Banks said as he held up a dark-colored specimen. “It looks a bit grotty but that’s kind of what fossil coral looks like at the bottom of the ocean.”

The importance of the discovery lies with its location in the deep sea about 1,600 feet below the surface.

These cold-water corals support important marine ecosystems — and they are as vulnerable to climate change as the more recognizable shallow, tropical reefs.

“You have huge areas of the world’s oceans which are completely unmapped which are all deeper than people can easily reach by research diving — like 95% of the world’s oceans,” Banks said.

Michelle Taylor, the other scientist aboard the Alvin, said that when the submersible’s outside cameras illuminated the breathtaking view of the reefs, it was like shining a light on the global importance of deep-sea corals.

“These areas are beautiful. They’re diverse. They are going to be impacted by climate change but for the moment it’s out of sight, out of mind,” Taylor said.

Taylor studies deep-sea corals with an eye toward learning how to protect them. Some of the Galapagos specimens are being shipped to her lab at the University of Essex in England for study and analysis.

With the Galapagos discovery, researchers like Taylor can begin to understand the impact of climate change.

“We are going to spend time cataloging all of the animals we saw, the density of them, how many of them there were — we’re going to use that as a baseline,” she said.

Basically, in future dives, researchers can use the baseline to see how changes in the ocean’s temperature and higher acidity caused by carbon absorption have affected the reefs.

Taylor said that scientists in geochemistry at the UK’s University of Bristol will take a different tack — going back in time to study the gene history of coral fossils.

“You can find what the chemistry of the ocean around Galapagos was like 10,000, 50,000, 100,000 years ago, just by looking at coral fossils,” she said. “Then, we can look at all the live stuff we collected and we can start seeing just how different the environment is for these corals now than it was then.”

The Galapagos are an archipelago of volcanic islands about 600 miles from Ecuador’s mainland that sit at the intersection of several ocean currents. They famously support an unrivaled diversity of land and marine life.

The islands have long been a center for naturalistic research. It was Charles Darwin’s expedition here in 1835 that resulted in his seminal work, “On the Origins of Species.”

The discovery has done little to pierce the usual routines of the islands. At a dock not far from the Darwin Foundation, local fishermen unloaded their daily catch. Sea lions lounged on nearby benches. Tourist boats returned to port laden with sated visitors after a day of snorkeling.

But scientists around the world are fascinated by the discovery. Sebastian Hennige, a leading researcher of ocean acidification and its impact on deep-sea coral at the University of Edinburgh, said deep-sea corals play a big role in the ocean.

“They’re rainforests of the deep. They create these vast structures, and they support thousands of different species,” he said. “So, they’re really, really important in terms of the framework and the habitats they build, and the other species which they support.”

He said the Galapagos discovery will result in knowledge vital to the conservation of deep-sea corals.

“The first part in solving a problem is being aware of the existence of the ecosystem, and then how that may be under threat from different things in the future,” Hennige said.

Hennige and the other scientists all agree that more deep-sea exploration is needed to fully understand the impact of climate change on cold-water corals. But these expeditions are complex, expensive and sometimes risky, as seen recently by the implosion of a submersible on a private expedition to the Titanic wreck.

Daniel Fornari is a marine geologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute on Cape Cod, which operates the Alvin submersible. Fornari, the co-leader of the Atlantis expedition, said the discovery of the Galapagos reefs has advanced research tremendously.

“The fact that we discovered it and mapped it reasonably well so we can go back to do more work on it is huge from the point of view of scientific productivity and the ability to not have to wait years and years to write yet another proposal and get yet another ship,” Fornari said.

Banks, the Darwin Foundation scientist, is organizing another expedition off Galapagos for this fall.

He and the other scientists are pretty sure there are more reefs down there that are yet to be discovered, and this may lead to more research that will ultimately protect those rainforests of the deep ocean.

Editor’s note: Support for this story was provided in part by a PSC-CUNY Award, jointly funded by The Professional Staff Congress and The City University of New York.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?