The US midterms ‘blue wave’ has mixed results for the environment

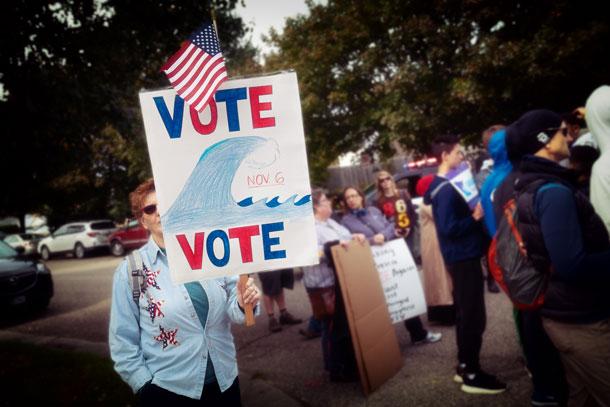

A Democratic “blue wave” campaigner at the Greater Than Fear rally and march in Rochester, Minnesota.

The 2018 US midterm elections ushered in a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives — along with new Democratic governors — who pledge to act on climate change. It also ushered out some climate-denying Republicans.

Yet overall, the elections had mixed results for the environment, despite the Democratic successes, says Peter Dykstra, an editor with Environmental Health News and DailyClimate.org.

For example, two almost identical clean energy initiatives in the states of Arizona and Nevada had different outcomes.

In Arizona, Tom Steyer, the billionaire activist, was responsible for much of the $23 million spent to support an initiative to pass a clean energy measure that would have required state utilities to use 50 percent clean energy by the year 2030. The initiative lost primarily because utility companies spent even more money — about $30 million.

In Nevada, however, a similar measure that requires 50 percent clean energy by 2030 passed and money was not quite as big a factor, Dykstra says.

Florida passed a measure that would ban offshore drilling in state waters, while voters in the state of Colorado rejected a measure that would have restricted oil and gas drilling on state-owned land. In Washington State, a proposed tax on carbon was defeated by “an absolute avalanche of fossil fuel industry money,” Dykstra says.

Marsha Blackburn, a Tennessee congresswoman and Tea Party darling, won the election as a US senator, replacing retiring Republican Bob Corker. Blackburn is best known in environmental circles for leading an effort in 2012 against energy-efficient light bulbs on behalf of an incandescent light bulb manufacturer in her district.

On the other hand, another Tea Party hero, Congressman Dave Brat from Virginia, lost his re-election bid. Brat became a phenomenon four years ago when he challenged and defeated Eric Cantor in the primary for a congressional district in suburban Richmond, Virginia. Cantor was house majority leader and thought of as a potential future speaker of the house, yet Brat came of out of nowhere, beat him in the primary and then won the general election.

Brat served four years in Congress, compiling a lifetime League of Conservation Voters score of 1 percent. He was defeated by a Democrat named Abigail Spanberger, also an unknown in politics.

Among the anti-environment GOP remembers now gone: California Republican Dana Rohrabacher, an avid surfer and an equally avid opponent of the Clean Water Act and other measures to protect the ocean; Darrell Issa, a retiring Southern California congressman who pushed to investigate climate scientists; and Lamar Smith, the veteran Texas congressman who recently chaired the House Science Committee and, says Dykstra, used it as “sort of a chamber of inquisition for climate scientists.”

Smith is being replaced by Chip Roy, another Republican climate change denier. Roy has called concern about climate change “hysteria” and expressed doubt about humanity’s contribution to the problem.

Another Texas Republican, “Smokey Joe” Barton, retired and was replaced with a new GOP member. Barton got his nickname from environmentalists because he was a close friend to all manner of polluters. “Joe Barton’s claim to fame was demanding that President Obama apologize to BP for being so mean to them over the 2010 Gulf Oil spill,” Dykstra explains.

Carlos Curbelo, a Republican from South Florida who started and co-chaired the Climate Solutions Caucus, also lost his re-election bid, and, in Illinois, a Democratic scientist named Sean Casten was elected, which Dykstra says has environmentalists and other scientists excited.

“There’s been a push for the past year or so to get scientists more involved in politics and to have some actually run for office,” Dykstra explains. “Casten has postgraduate degrees in molecular biology and in engineering. He’s also a successful entrepreneur in clean energy. He took on a six-term congressman named Peter Roskam in the Chicago suburbs.”

“Roskam had already been under environmental criticism for ignoring pollution from a local factory,” Dykstra continues. “Casten came in with a new voice for suburbs ready for a change. Expect him to be a loud, well-educated, role model of a successful clean energy entrepreneur in the House of Representatives.”

In Maine, a Democrat is replacing Governor Paul LePage, whose most famous environmental moment came when he dismissed the risks of BPA, the potential endocrine disruptor, by saying the worst case would be that “some women may get little beards.” Maine’s new governor is now a woman, Janet Mills.

Not so long ago, the environment was a bipartisan issue, Dykstra notes. A Republican president, Richard Nixon, started the EPA. In his 2008 campaign for president, Senator John McCain advocated for strong action to slow global warming.

“It’s hard to say when we’ll get back to that, or if we’ll get back to that,” Dykstra says. “All we know is that we’re not there now and it’s going to be a long road ahead. And if the two parties want to define themselves on differing environmental values, we’ll be headed in the wrong direction again.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.