No shame in sisig: Filipino chefs and scholars say they are overcoming a century of stereotypes

Sisig, a Filipino dish, is pictured at a restaurant in Manila, Philippines on July 28, 2017. Anthony Bourdain told CNN Philippines in 2017 that Filipinos in the US "maybe underrated their own food," and said that sisig would be the break-out dish.

At 4 p.m. on a Sunday, it's not quite lunch or dinnertime but Ihawan is packed. Filipinos would call this meal merienda cena: afternoon snacktime blending into dinner. With its Wall of Fame of Filipino celebrities and soundtrack of Pinoy hits, this restaurant in Woodside, Queens, prides itself on giving Filipinos a taste of home.

And as far as I can tell, everyone in here is of Filipino descent.

Some food writers might look at the all-Filipino dining room and conclude Filipinos are too ashamed of their food to bring white people here. There have been a number of stories about Filipino food in the US that talk about a feature of Philippine culture called hiya.

On a 2017 episode of the podcast “Feast Meets West,” host Iris Van Kerckhove mentioned an article in the Washington Post that talked about Filipino immigrants in America having felt a sense of shame or dishonor around their food. “They use the term hiya … and it’s weird because it’s not something that I’ve heard other Asian cultures feel about their food,” she said.

According to stories like these, food shame comes from something inherent to Filipino culture. In 2014, New York restauranteur Nicole Ponseca told PRI that there are many potential reasons why Filipino food hasn't taken off, including cultural and historical issues, as well as the difficulty in finding investors. She cited hiya, too: "It is because when you’re colonized over so many years, you don’t value your own culture, even though we have so much pride."

It’s time to clear something up. Yes, the literal translation of shame is hiya. But in Philippine culture, hiya has a much deeper meaning. Hiya is part of a value system that guides how people act.

“All of this really is a reflection of how we see ourselves as connected to other people,” explains E. J. Ramos David, an assistant professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage who studies the mental health effects of colonialism on Filipinos. “We don't just see ourselves as an individual person that ‘I will do whatever I want, I don't care what everyone else thinks.’”

Hiya means accountability to others: your family, friends or community. It's knowing that they have a stake in your actions and they will judge. It’s a sense of responsibility for upholding community standards. And it is shameful if you fall short.

So, how did this get translated into Filipinos being ashamed of their food? At some point, that cultural meaning of hiya got confused with a different meaning of hiya: the shame minorities feel when their food is ridiculed.

“You know, going to school and having adobo, and being like, ‘Oh what is that brown stuff? Is it dog?'" Natalia Roxas says these are just some of the comments she used to get about the lunches she’d bring to school. Now, she and Sarahlynn Pablo have founded Filipino Kitchen, a pop-up that organizes food and heritage events from their base in Chicago.

At a recent workshop for college students of Filipino background, Pablo asked attendees if they’d ever been called or heard the term "dogeaters" as a pejorative for Filipinos.

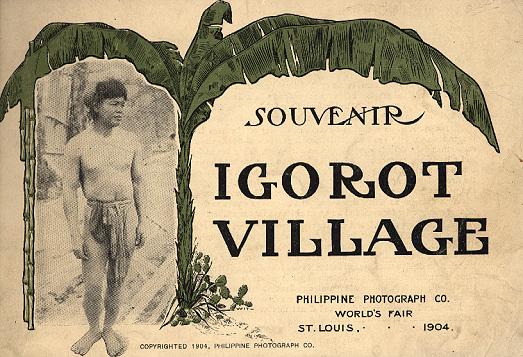

“A third of them raised their hands,” Pablo says. “It’s a century ago but that idea still persists.”

A century ago, a fake village of real indigenous Filipinos was a big hit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Crowds gawked at brown people performing a dog-eating ritual. As the US began an almost 50-year occupation of the Philippines, Filipinos were depicted as savages who had to be civilized.

In the Philippines, the American colonial government set up the public school system. Filipino kids were taught that their local food was unhealthy. Western dishes and processed food such as canned milk were presented as superior.

Though the Philippines gained independence in 1946, the effects of colonialism run deep. Filipinos are quite familiar with American tastes and how their food is presented in the US. Filipinos are rarely featured in American media, but when they are, the spotlight is usually on the most extreme aspects of their culture. Balut, fertilized duck egg, was featured as a gross food challenge in 2002, later revived in 2013 on YouTube, on the NBC show "Fear Factor." It was later part of eating challenges on "Bizarre Foods" and "Hell's Kitchen," and various incarnations of "The Amazing Race."

When the only representations of your culture available are negative, it’s no surprise if some Filipinos internalize all that shaming.

But even those who unapologetically love the food can’t escape those prejudices. Amy Besa is most well-known ambassadors of Filipino food in the US. She and her husband, Romy Dorotan, own the restaurant Purple Yam in Brooklyn. When they first started out, they wanted to feature the flavors they loved. But they knew what they were up against.

“If we said, ‘Oh, this is a Filipino restaurant,’ then all kinds of limiting stereotypes will come in,” Besa says. “We knew that there were things that some non-Filipinos were squeamish about.”

When she heard that some people were attributing this type of caution to hiya, saying Filipinos were ashamed of their food, she was angry. She thinks citing cultural sources of shame for why Filipino food isn’t better-known here puts blame in the wrong place.

“There are barriers that we did not create that prevent us from equal access and support to move our food towards that place where we want it to be. But then, Filipinos love their food and are proud of it. And if we’re able to move in spite of all the barriers, it's because, ‘Oh, they allowed us.’” Besa says. “So when we make progress, guess who gets credited for it? What? Andrew Zimmern and Anthony Bourdain? Excuse me!”

Anthony Bourdain told CNN Philippines that Filipinos in the US "maybe underrated their own food," while proclaiming that sisig would be the break-out dish.

But no one has to tell Filipinos not to be ashamed to enjoy crunchy, garlicky, rich, spicy sisig, chopped meat from a pig's face and ears, sizzling and gooey with a raw egg cracked over it.

David, the professor, says it's not Filipinos who've underrated this food.

“The conversation about why Filipino food has been ignored by mainstream America for so long — well, the reason for that is mainstream America.”

Tordesillas's story was produced with help from Feet in 2 Worlds.