How do consumers make good choices about clothes? Spider silk and brand transparency.

Employees stitch together blue plaid shirts in a factory in China in 2013. Wages have risen in China, but it still controls more than a third of apparel exports.

It took him 32 years, but scientist Sam Hudson and a team of other researchers have found a way to produce silk without silkworms.

Unlike fabrics such as polyester or nylon, there’s no petroleum-based plastic. Unlike rayon, there’s no toxic chemicals or deforestation involved.

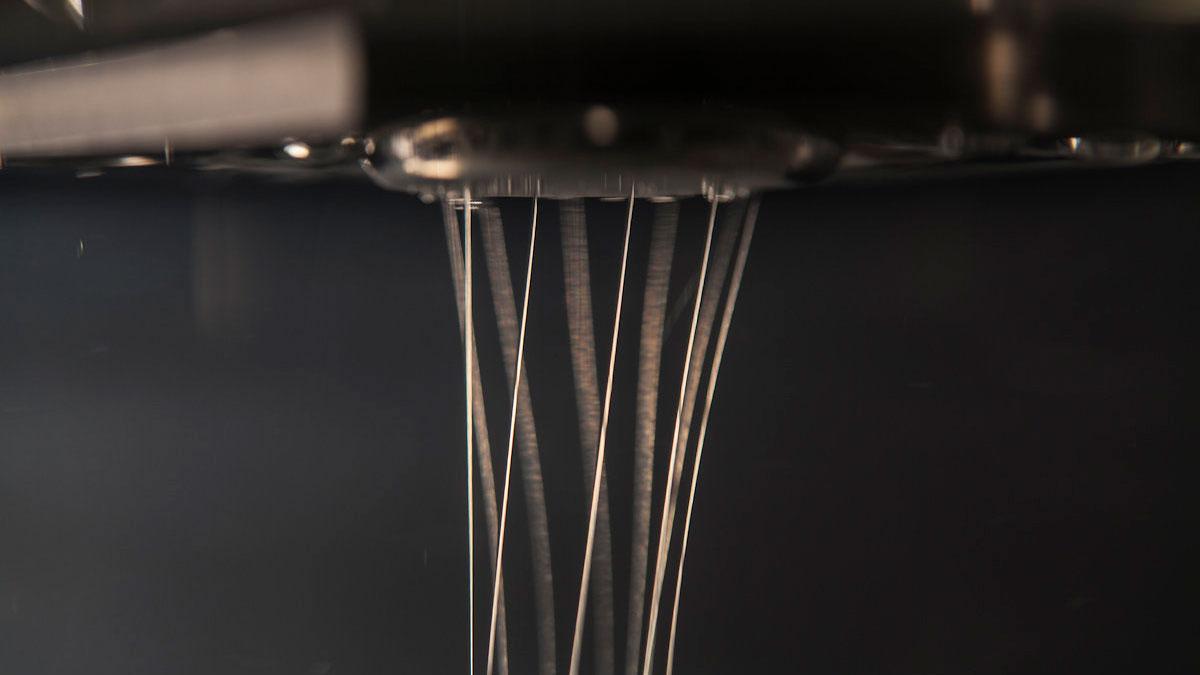

It’s a yeast that when you add sugar and vitamins, it grows — secretes, to be precise — a spider silk.

“You take a tank of water, put the yeast in it and put in the sugar and the salts and the vitamins,” explains Hudson, a polymer chemist at the College of Textiles at North Carolina State University. “The yeast starts growing and reproducing. It gets a little cloudy, but the yeast manufactures this protein and secretes it out. [We] filter it out and dry it, and we get a whitish powder. That’s where I step in. I take that powder and dissolve it into a solvent, and then we can spin it.”

Hudson is working with Bolt Threads, an Emeryville, California-based biotech startup, to perfect the process of creating spider silk thread. So far, they’ve created 50 neckties and a yellow silk used by designer Stella McCartney in an exhibit for MoMA in New York City called, “Is Fashion Modern?”

Hudson and Bolt Threads' new fabric is just one solution to the fashion industry’s pollution problem. The garment industry is also guilty of underpaying and overworking workers, polluting the sites where clothes are made and overproducing so much that cast-off clothes are hurting economies in developing countries and filling landfills.

Hudson has spent his entire professional career as a chemist chasing a feasible product. “It took me 32 years to even hold something in my hand,” he says.

Bolt is nearly able to make a 1-ton batch of silk protein about every three days. How much silk is that? According to Hudson’s math, that one batch is equal to the silk of 20,636,363 spiders.

“You just can’t farm spiders,” he says. “We’ve tried.”

He’s tried a lot of things to find a way to grow the silk protein found in spiders.

“The bacteria didn’t work; the potatoes didn’t work; the silkworms didn’t work,” he says. “We never had access to sufficient quantities of these materials from some kind of biotech process. We finally found the right organism to make this protein.”

This story is a part of a special Across Women's Lives series. Read more: Wear and Tear series: The women who make our clothes and How a sweatshop raid in an LA suburb changed the American garment industry and Her job at the mill bought her a new, better life. And, participate in our interactive: How fair is your fashion? Take the quiz.

The resulting fabric is a silk that can be engineered for more stretch, easy washing or other desirable qualities. And when a consumer is done with it? Since the silk comes from natural materials, the end product will be biodegradable.

But it’s a long road before all our clothes will be made from spider silk.

“It’s not going to be a commodity like polyester,” Hudson says. “But hopefully, 100 years from now, most of the fibers will be made from some biological process and not petrochemicals.”

Worldwide production of polyester and nylon has exploded since it was first created in the 1930s. Both materials are made from petroleum-based plastics, and when these things hit a landfill, they don’t biodegrade.

Some experts estimate that half of the world’s clothing supply is made from synthetic materials and these clothes shed plastic microfibers during the washing cycle, which are now being found all over the planet.

So, what should consumers do until spider silk is more common?

Jocelyn Whipple is a materials expert and a member of the global coordination team for Fashion Revolution, an ethical fashion advocacy group.

“I think the very first thing that people can do is take the time to look at your label before you even buy something and inform yourself about fibers,” Whipple says.

Her advice: Look for recycled polyester and secondhand clothing and avoid blends, which are nonrecyclable and tend to shed more fibers during washing.

Polyester and nylon that hasn’t been blended with other fabrics can be melted down and turned back into another fabric. She points to companies like Adidas, which is experimenting with recycled polyester and reclaimed ocean waste. Other companies are remaking nylon fishing nets into clothes.

“If [polyester] remains in its 100 percent form, it is actually recyclable,” Whipple says. “It’s not fresh oil, basically.”

Whipple says consumers should also look for 100 percent organic cotton and organic wool products and simply know more about what they’re buying.

“I think the very first thing that people can do is take the time to look at your label before you even buy something and inform yourself about fibers,” she says.

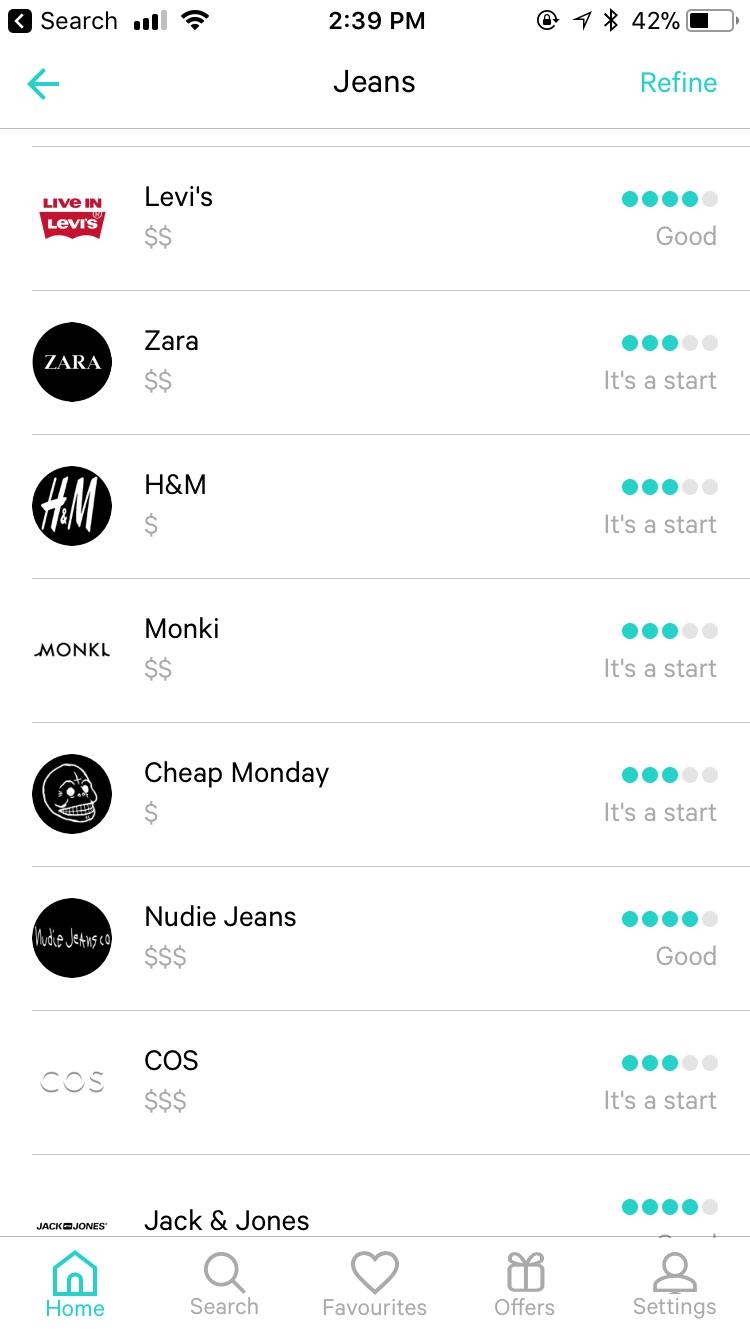

Sandra Capponi is making things even easier for consumers. Capponi is the co-founder of Good On You, an app that launched in Australia in 2015 with ethical ratings for hundreds of brands.

“We start with the premise that we’re all about empowering shoppers to shop better and to shop according to values that are important to them,” she explains. “I think it is important to recognize there is a person behind every piece of clothing we wear. So, somebody is paying the price in the end if a T-shirt is only costing you a few dollars.”

Good On You uses publicly available information from companies to evaluate them based on impacts on people, the planet and animals.

“We find that brands are simply not communicating to the public,” Capponi says.

The app uses a team of 30 volunteers, called “ethical detectives,” and has rated more than 1,200 brands and plans to expand soon to several thousand.

In the app, users can directly message companies about the ratings.

"One individual is just one voice," Capponi says. "The power of Good On You is we're building a collective community, a collective voice, that really will have the power to shift the culture and the behavior of businesses."

If Capponi had to give consumers one tip for making better clothing choices?

“Ask yourself, ‘Do you really need this?’”

Stay tuned for more of AWL's "Wear and Tear" series this week:

Wednesday: How the Rana Plaza factory collapse changed the global garment industry.

Thursday: Like mother like daughter — how two generations of Bangladeshi women view their work making clothes for Americans.

Friday: The city that H&M built.