For one South African house cleaner, this year’s big drought means crying, hungry children

Mavis, a housekeeper from the Pretoria township of Mamelodi, depends on her garden to help provide for her five children and seven grandchildren. But with this year's region-wide drought, her garden is just a dusty patch of seedlings. “I want rain every day,” she says.

In my little garden here in Pretoria, sprinklers automatically go off every morning at 8. They’re doing a good job. My cucumbers have outgrown their trellis, I can’t keep up with all the spinach, and, as usual, mint and morning glories are trying to take over.

Without the irrigation system, my garden would look very different. It would look more like my friend Mavis’ garden — a dusty patch of seedlings.

Mavis lives in the township of Mamelodi. She’s a domestic worker who cleans homes in neighborhoods like mine to support her five children and seven grandchildren. As usual, she’s put in cucumbers, spinach and green beans in her garden next to her small cement house.

But this year, she says, “it’s not working.”

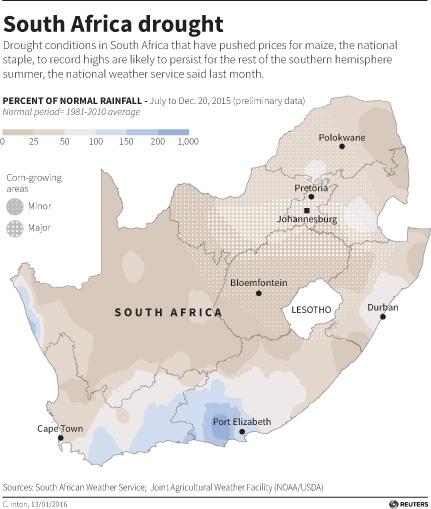

It’s not working because South Africa is suffering through its worst drought in more than 35 years. And Mavis doesn’t have sprinklers like I do.

Normally this time of year it rains every afternoon — you can practically set your watch to the 4 o’clock downpour. But this year, there’s just more sun. The first of the seasonal rains should have come in October, but it didn’t start raining this year until December, and then only sporadically.

That’s bad news for Mavis, who really counts on her garden.

“I have a budget for every month,” she says as she feeds cracked corn to her baby chicks. “When it didn’t rain and nothing grow up, then I use my budget more. (And) the children are crying, hungry.”

Mavis’s garden doesn’t grow, and at the same time the price of the staple food here in South Africa, a cornmeal called pap, has gone up by roughly 50 percent. The drought is partly responsible for that too, because the country’s breadbasket region has been particularly badly hit. Meanwhile the price of imported corn has gone up because of South Africa’s weak currency.

Other countries in the region are even worse off, especially Zimbabwe.

“The harvest [in Zimbabwe] in April is likely to be extremely poor,” says David Orr of the World Food Program in Johannesburg. In at least one province there, Orr says, three-quarters of the crop may be written off.

Orr says almost 2.5 million people are living with food insecurity in Zimbabwe, and that the number is expected to rise. Zimbabwe’s government has declared a state of disaster and hopes international donors will step in to help.

Nearby Malawi and Zambia have also been hard hit, and in Mozambique the price of corn has nearly doubled. All told, roughly 16 million people across the region are affected.

There aren’t many good options for relief in the short term. But Orr says there are things governments in the region can do to hedge against drought in the future, such as investing more in irrigation and water conservation, using drought resistant seeds, even moving away from thirsty crops like corn to others that require a lot less water.

Orr says it’s especially important to do these things now, because while the current drought is likely tied to the temporary global El Niño event, climate scientists predict that southern Africa will be generally hotter and drier in the future.

The ins and outs of El Niño and climate change are a little abstract to Mavis, but she knows something’s wrong.

“I think it’s a change of weather, I don’t know,” she says. “Because everything now is changing.”

Since she was a girl, Mavis says, she’s waited for the weeklong soft rain known as Nedupi to plant her crops. Nedupi just didn’t come this year.

But she’s holding out hope that the prayers for rain will still be answered.

“I want rain every day,” Mavis says. “Even if it rains [when] I’m on the street still coming home, going to work, I don’t care. When it rains we must say ‘thanks God,’ because it washes us. Then we be fresh.”

For now, the government of South Africa seems to be taking the same approach. They’ve declined to declare a state of emergency like Zimbabwe and are hoping the late rains that have come will be enough to salvage this year’s harvest.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?