Brazil is set to become the world’s biggest soy producer — and that might be bad news for its forests

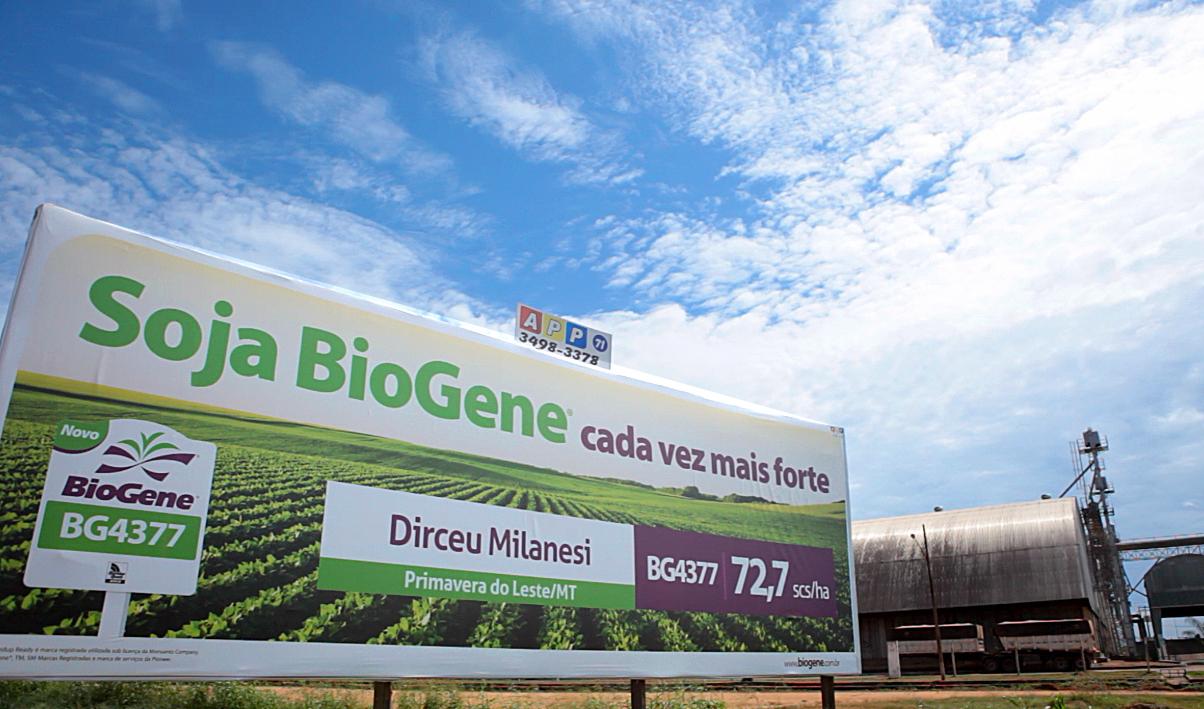

A billboard for soybeans in Mato Grosso, Brazil. The region is likely to make Brazil the world’s top producer of soybeans, but the boom in production has come at the same time as a rise in deforestation.

In the soy bean world, all eyes are now on the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil.

It’s covered by millions of acres of industrial farms and deep green soy fields. If this year’s harvest — the best in Brazilian history — comes in as expected, Brazil is poised to surpass the US and become the world’s largest soy producer. Soy beans have boosted Brazil’s economy and even brought President Dilma Roussef to Mato Grosso to congratulate farmers in person.

But in a nearby indigenous village, no one is celebrating. The boom in soy production coincided with a spike in deforestation. And Hiparidi Toptiro, an activist from the indigenous Xavante people, says local soy farmers are willing to do anything for a chunk of the forest where the Xavante live.

“Throughout our lands, people show up wielding false deeds to the area,” Toptiro says. “And they have begun to plant soybeans inside our lands. They pay off one of our villages with a little money, which complicates the relationship between all of us in the reserve. “ He calls it dividing and conquering with trinkets.

At the edge of his land is a highway bridge over a dark river, which separates the Xavante forests and tropical savannah from industrial soy crops.

“The Brazilian settlers on their side aren’t allowed to get too close to the river,” Toptiro says. “But their people have invaded our lands several times. We’ve contacted authorities but no one has ever answered us.”

But there is an even larger threat looming: The end to a global ban on soybeans grown on newly cleared forest land. In 2006, Greenpeace spearheaded the campaign that led to the moratorium. Much of Brazil’s soy is sold as chicken feed to international fast food chains, so activists protested in European McDonalds restaurants wearing chicken suits.

The protests worked. About 75 percent of Brazilian soy buyers agreed to reject any soy from recently converted forests. Researcher Daniel Nepstad from the Earth Innovation Institute, a US-based NGO, says the ban has been effective.

“It has fulfilled an important purpose,” he says. “Less than one percent of soy in the Amazon today is associated with deforestation.”

And when the moratorium ends in December, Nepstad thinks it will have little effect on forests. The bigger issue, he says, is getting more use out of the land that's used to raise cattle. It's called "cattle intensification" — getting more meat per acre of grazing land.

“Soy hasn’t really needed that much deforestation,” he explains. “Cattle intensification is taking place at such a pace that it’s basically opening up pastures that can be converted to soy without cutting down another tree.”

Former Brazilian cattle rancher Tom Dezan agrees. He says getting more use out of already cleared lands is one of the keys to saving Brazil’s forests.

“If we use the land like this that has already been worked, it would not be necessary to cut more trees,” he says, standing in a typically undergrazed cattle pasture deep in the Mato Grosso countryside. "The quantity of land in this condition in Brazil is very high."

If Brazil can take advantage of all this fallow land for better grazing, he says, it could save a lot of trees.

A lot of trees — but enough of them? For now, cattle grazing may be the biggest threat — and biggest opportunity. But with the moratorium about to disappear, the fear is that big business are coming to slash, burn and plant Brazil's forests out of existence.

In the soy bean world, all eyes are now on the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil.

It’s covered by millions of acres of industrial farms and deep green soy fields. If this year’s harvest — the best in Brazilian history — comes in as expected, Brazil is poised to surpass the US and become the world’s largest soy producer. Soy beans have boosted Brazil’s economy and even brought President Dilma Roussef to Mato Grosso to congratulate farmers in person.

But in a nearby indigenous village, no one is celebrating. The boom in soy production coincided with a spike in deforestation. And Hiparidi Toptiro, an activist from the indigenous Xavante people, says local soy farmers are willing to do anything for a chunk of the forest where the Xavante live.

“Throughout our lands, people show up wielding false deeds to the area,” Toptiro says. “And they have begun to plant soybeans inside our lands. They pay off one of our villages with a little money, which complicates the relationship between all of us in the reserve. “ He calls it dividing and conquering with trinkets.

At the edge of his land is a highway bridge over a dark river, which separates the Xavante forests and tropical savannah from industrial soy crops.

“The Brazilian settlers on their side aren’t allowed to get too close to the river,” Toptiro says. “But their people have invaded our lands several times. We’ve contacted authorities but no one has ever answered us.”

But there is an even larger threat looming: The end to a global ban on soybeans grown on newly cleared forest land. In 2006, Greenpeace spearheaded the campaign that led to the moratorium. Much of Brazil’s soy is sold as chicken feed to international fast food chains, so activists protested in European McDonalds restaurants wearing chicken suits.

The protests worked. About 75 percent of Brazilian soy buyers agreed to reject any soy from recently converted forests. Researcher Daniel Nepstad from the Earth Innovation Institute, a US-based NGO, says the ban has been effective.

“It has fulfilled an important purpose,” he says. “Less than one percent of soy in the Amazon today is associated with deforestation.”

And when the moratorium ends in December, Nepstad thinks it will have little effect on forests. The bigger issue, he says, is getting more use out of the land that's used to raise cattle. It's called "cattle intensification" — getting more meat per acre of grazing land.

“Soy hasn’t really needed that much deforestation,” he explains. “Cattle intensification is taking place at such a pace that it’s basically opening up pastures that can be converted to soy without cutting down another tree.”

Former Brazilian cattle rancher Tom Dezan agrees. He says getting more use out of already cleared lands is one of the keys to saving Brazil’s forests.

“If we use the land like this that has already been worked, it would not be necessary to cut more trees,” he says, standing in a typically undergrazed cattle pasture deep in the Mato Grosso countryside. "The quantity of land in this condition in Brazil is very high."

If Brazil can take advantage of all this fallow land for better grazing, he says, it could save a lot of trees.

A lot of trees — but enough of them? For now, cattle grazing may be the biggest threat — and biggest opportunity. But with the moratorium about to disappear, the fear is that big business are coming to slash, burn and plant Brazil's forests out of existence.