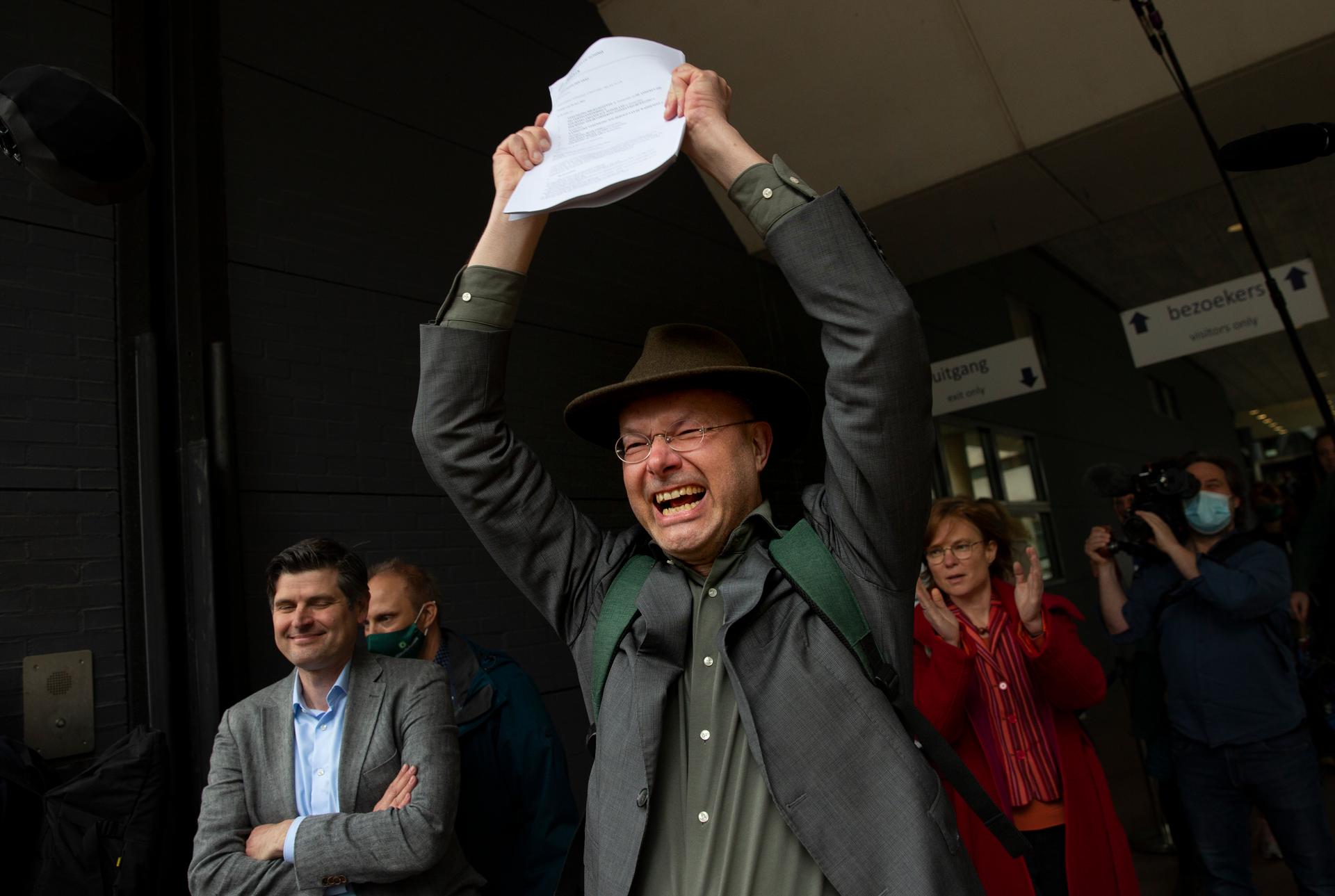

A federal court in the Netherlands ruled last week that the oil and gas company Shell failed to respect human rights, by contributing to global warming — making legal history.

Related: Fossil fuels cause 1 in 5 premature deaths worldwide, study says

The ruling is part of a larger trend of using the courtroom to hold powerful governments and corporations accountable for their roles in contributing to climate change.

In another case in Canberra, a group of eight Australian teenage environmentalists lost their court bid last week to force the federal government to ban a coal mine expansion. Environment Minister Sussan Ley is considering whether to approve an expansion of Vickery mine in New South Wales state, and the teenagers sought an injunction preventing the expansion. Their lawyer still claimed victory in the federal court’s ruling that the government has a duty to prevent future climate harm.

Related: Spiritual leaders seek to spur an ‘ecological conversion’

Joana Setzer is a climate litigation expert at the London School of Economics. As part of her research, she keeps a list of the hundreds of climate-related cases working their way through the courts in countries around the world. She discussed the growing trend with The World’s Marco Werman.

Related: West African villagers take on an American oil giant in new novel

Marco Werman: So, Joana, last week’s verdict would essentially force Shell to sell less oil and gas. What is the significance of the verdict as you see it? How big of a deal is it?

Joana Setzer: So, this is really a big deal. It was a lawsuit filed by a Dutch nongovernmental organization and 17,000 individuals who are supporting the case. And the court concluded that Shell has to reduce their CO2 emissions by 45% at the end of 2030. That really means changes to their whole corporate policy and a precedent that could go beyond Shell, and beyond the Netherlands. This is the first time that a climate case [has been] brought against a corporation, trying to get the corporation aligned to the Paris goals and also to the climate science. This is the first time that a company is told to reduce their emissions by a court.

How do you think those activists will use the precedent this Dutch ruling sets in future court cases?

So, if we compare to the other case that was brought also in the Netherlands, against the government, asking the government to step up their ambition and to have more stringent reduction targets, that case was brought by a Dutch nongovernmental organization called Urgenda. What happened was that a number of other organizations started thinking how they could reproduce the case in their own jurisdictions. So, you see Urgenda-type cases in South Korea, Brazil, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, and the list goes on and on. So literally, lawyers [were] studying the case, making the necessary adaptations for their own jurisdiction and filing similar cases in different countries. So, if you imagine something similar happening to this [Shell] case, we could imagine how this case and the decision would travel to other jurisdictions.

Yeah, and we don’t have to imagine too hard. On top of last week’s case against Shell, in May, a group of young people in Germany successfully sued the federal government there over its climate plan. Also this week, a group of Australian youth stopped a coal plant from opening. There are other examples in Portugal and Ireland, and other places. Can you talk about the increase in climate lawsuits recently?

Since 2015, precisely since that decision in the Urgenda case, the number of cases of climate litigation in the world has increased significantly. And when I say increased significantly, I’m talking about these high-profile strategic cases that have a clear target, either against the government or against corporations, and that aim to drive ambition, or to show society who the actors [are] that are mostly responsible for the problem, and also for the solution. So it is courts, it’s lawsuits being used, not just to resolve individual problems, but to create a case that is going to send a message.

There were a lot of lawsuits that came to the courts following the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Can you help us understand what the agreement did to open up all these legal challenges to governments, energy companies, other big business? I mean, were these lawsuits and plaintiffs inspired by the agreement, or did the agreement actually have avenues built in for legal challenges if COP [Conference of the Parties] was not abided by?

On the one hand, you would think that having the Paris agreement would have meant less litigation. You would think, well, it took so long for the international community to agree on an international agreement. We have thousands of laws and policies in literally every country in the world addressing climate change. But what happened was that many started noticing that the international commitments made by heads of state, and even national legislation, was just on paper, that those commitments were not being translated into action on the ground. And this is really where litigation comes in. It comes in this huge question mark that we are left when we see that all those commitments are inconsistent with action.

So to wrap up, Joana, how do you see climate litigation fitting into the bigger picture of climate change solutions? What do you see as its limitations, but also its potential?

It does have a very important role to play. I also see litigation as a last resource. We would like to see more action, not more litigation. When you file a case, you have costs, you have a lot of uncertainty and it will take time. And we don’t have time. And we also can’t afford the risk of having unsuccessful cases one after the other. But, litigation brings the weight of accountability. It also brings the expectation from the population, who is tired of promises that are not delivered. You have litigation really driving action, but it’s hopefully something that we will see less, as I said. We cannot rely on litigation to solve the climate crisis.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.AP contributed to this report.