As hurricane season nears in Puerto Rico, a doctor tries to help pregnant women prepare themselves

Raúl Leandro was born at his grandmother’s house shortly after Hurricane Maria struck in September 2017. His parents, Raúl Malavé Cotto and Yahaira Molina Perez, planned to give birth at a hospital in San Juan, but when they showed up in early labor, they found the facility full of sand, without power, and attending only to emergencies.

Yahaira Molina Perez was 8 months pregnant when Hurricane Maria hit. In her town of Cidra, downed trees and power lines made roads almost impassable.

Molina wasn’t too worried, though — she wasn’t due for weeks.

But just five days after the storm she started having contractions.

The trip to the hospital in San Juan took twice as long as usual because the roads were such a mess. When she arrived, she found the hospital, which is located near the shore, full of sand and broken glass. Elevators and air-conditioning had gone with the power. She had to climb the steps to the maternity ward, where nurses had rolled up their pants and sleeves in the stifling heat.

Many of the island’s hospitals were unprepared for such a disaster and either closed their doors entirely or had to limit the services they offered to patients.

“I was thinking, ‘Wow, I did not prepare for this.’ I never even considered giving birth at home.”

Molina’s hospital was only handling emergencies, and she wasn’t ready to give birth. So, she and her husband, Raúl Malavé Cotto, headed back to Cidra. On the way, they stopped at Molina’s mom’s house, and Molina’s water broke. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, I did not prepare for this,'” she said. “I never even considered giving birth at home.”

There were no phones — no communication — but through the grapevine, they heard that an obstetrician lived in the neighborhood and they knocked on his door. He brought his wife, a nurse.

“I didn’t have my medical file with me. In other words, if at any point the doctor asked me something about my condition, I didn’t know what to tell him,” Molina said.

She said she could hear the emergency generator roaring as she labored, another reminder of the chaos outside. She was scared.

“I was yelling out of fear; I wasn’t yelling because of pain. I yelled from fear.”

“I was yelling out of fear; I wasn’t yelling because of pain. I yelled from fear.”

Related: Puerto Rico has not recovered from Hurricane Maria

But this is a happy story. After a brief labor, Raúl Leandro was born healthy.

On a recent, sunny day, the toddler squirmed in his father’s arms, pointing into the jungle just beyond the family’s hilltop house, searching for a Bobcat. The Bobcat in question was the small, front-end loader his father, who owns a landscaping business, used to clear roads after the storm. Molina said it’s her son’s favorite thing in the world.

Teaching preparedness

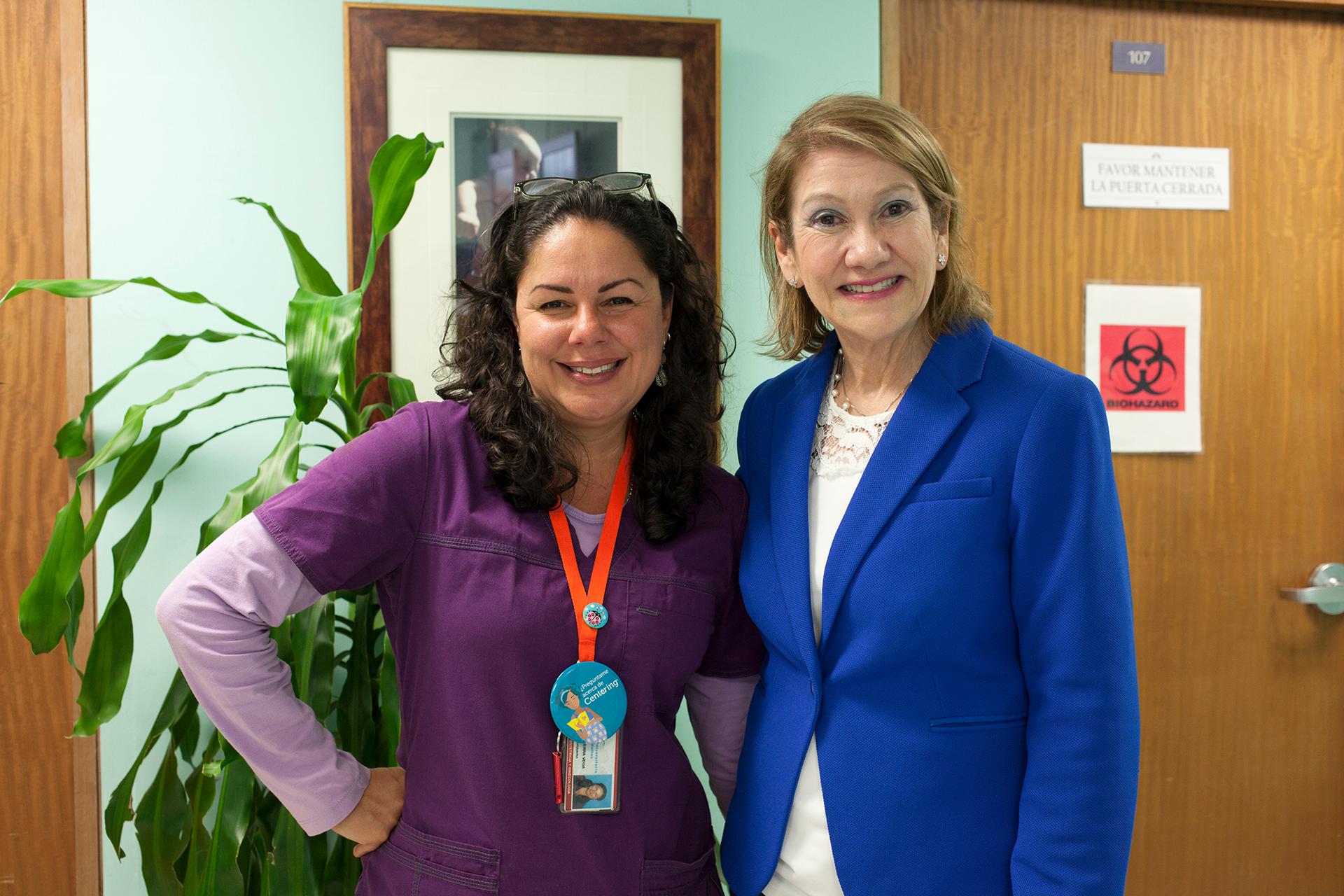

In San Juan, Carmen Zorrilla, an obstetrician at the island’s main public hospital and the principal investigator at the Maternal-Infant Studies Center, heard of several unplanned home births like Molina’s after the storm. It worried her. She started thinking about how her patients could better weather another such storm — if it comes. She found a potential solution in an existing program.

In 2013, in a first for Puerto Rico, Zorrilla introduced a nontraditional approach to care for women with high-risk pregnancies. The model, called Centering Pregnancy, relies on two-hour group prenatal appointments, rather than brief, one-on-one checkups. Funding issues and the hurricane put the program on hiatus, but it’s slowly coming back now. And Zorrilla thinks it can be adapted for hurricane preparedness.

At a recent appointment, nine pregnant women — each with a support person — filed into a small room in the hospital. They weighed themselves, measured their own blood pressure with a monitor and gave their data to a nurse.

“They are taking care of their own health, right then,” Zorrilla said. “They are empowered; they are involved in their care.”

Each session covers different aspects of pregnancy, and that day, the group discussed common gestational side effects. The facilitator, Dianca Sierra Vega, handed out cards, each with a different issue written on it. She told the women to act them out, charades style. Grunting, growling and clasping at various body parts, the women acted out headaches, swollen feet, aching backs, constipation and mood swings. After the group guessed each ailment, the facilitators explained the science of what’s happening to the women’s bodies. It was informal, and the women were engaged.

“That’s part of what they gain; and being part of a group, there’s social support.”

“That’s part of what they gain; and being part of a group, there’s social support,” Zorrilla said.

Initially, Zorrilla says, she introduced group appointments because the island has a high rate of premature, and underweight, babies. Studies show when pregnant women, particularly some populations like low-income black women, participate in group appointments, babies are likelier to be born closer to their due dates. No one knows precisely how the groups work, but Zorrilla thinks they reduce stress.

When the storm season officially begins in June, she’ll use the model to teach hurricane preparedness in new sessions. These appointments will cover everything from how to cut the cord to what supplies they should keep in the house to how to perform calming breathing exercises. The idea is to give the women practical know-how as well as the confidence to stay calm if a storm barrels toward the island.

Again

“The concept of group prenatal care is that you’re in control of your health,” Zorrilla said. “And having the information of what to do with an emergency labor and delivery, I think, it gives peace of mind.”

Yaisha Roja is one of the women in the new group. This is her second pregnancy, and she’s due in October — hurricane season.

“One should always take precautions. Perhaps there’s a hurricane, and there aren’t many hospitals open, there’s traffic. That’s why this is important.”

“One should always take precautions,” she said. “Perhaps there’s a hurricane, and there aren’t many hospitals open, there’s traffic. That’s why this is important.”

Zorrilla still thinks women should plan on hospital births. They’re safer, she said. But just in case there’s another disaster, she wants women to be ready.

“I say that we have community PTSD. Now that we lived through not just a hurricane, but the aftermath, the complete disruption of the power grid, everybody is concerned and now we know that we need to be ready for this.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?