Chávez’s revolutionaries caught between legacy and change in Venezuela

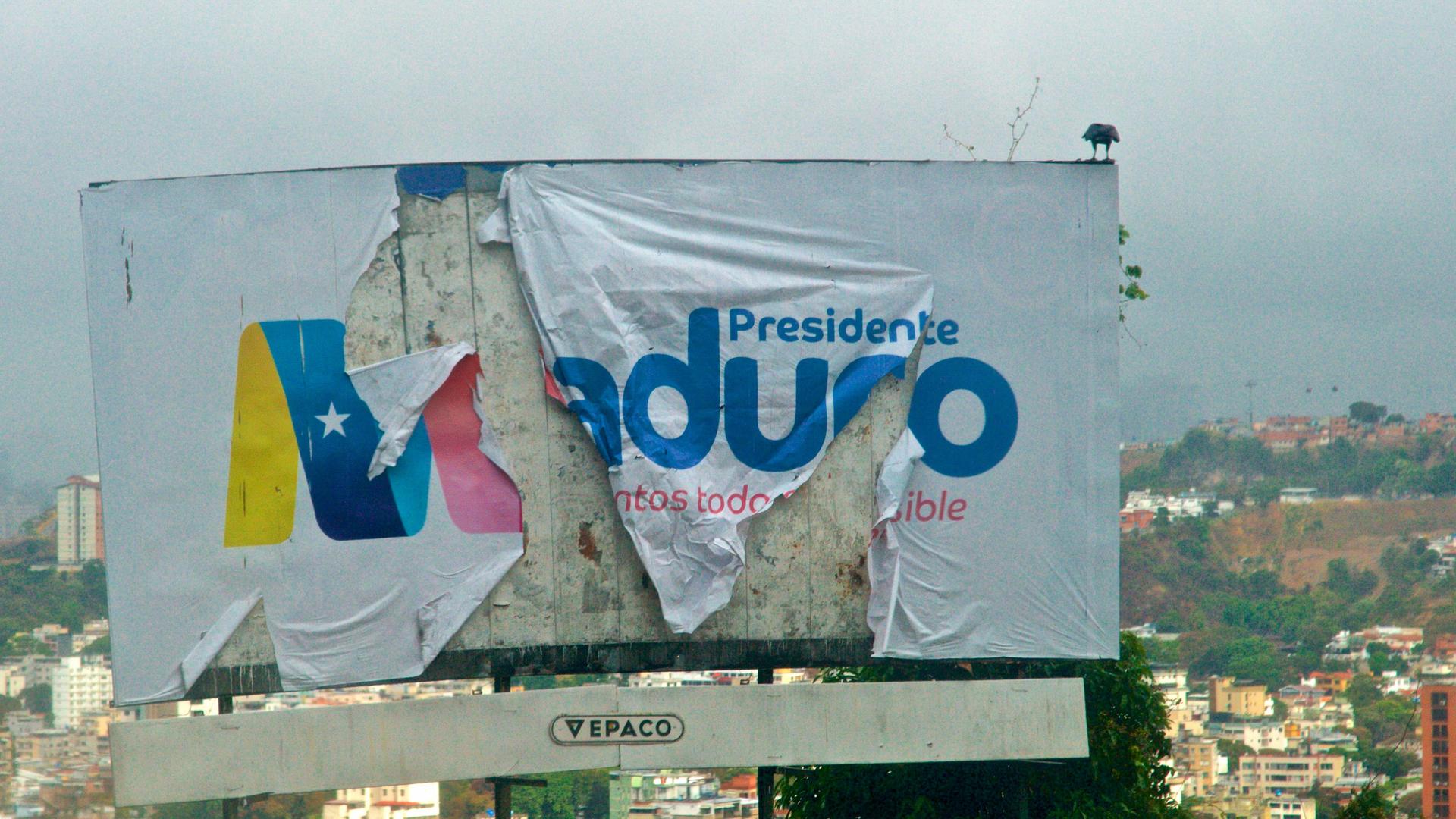

“Chávez eyes,” one of the Bolivarian Revolution’s most prominent symbols, has been painted on a gate in Caracas, Venezuela, Feb. 26, 2019. The image originated from Hugo Chávez’s 2012 presidential campaign. After his death, President Nicolás Maduro continued to use the image. By 2015, Reuters described Chávez eyes as the “most ubiquitous image in Venezuela of recent years.”

“It was all a Utopian dream,” Daidy Marcano said with disappointment, thinking back on her years as a supporter of Hugo Chávez and his Bolivarian Revolution.

For 20 years, the political movement dubbed the Bolivarian Revolution has governed Venezuela. Chávez’s socialist movement, named after 19th-century revolutionary Simón Bolívar, Venezuela’s founding leader, sought to restore ideals of freedom, equality and justice after the country’s bipartisan democracy, established in 1958, had become corrupt and self-serving.

“We felt a change was necessary to have a government more oriented to the people, to have more equality and justice and an equal share of Venezuela’s wealth for the benefit of Venezuelan men and women.”

When Chávez was elected in 1998, thanks to a wave of discontent with the status quo, “We felt a change was necessary to have a government more oriented to the people, to have more equality and justice and an equal share of Venezuela’s wealth for the benefit of Venezuelan men and women,” Marcano said.

Venezuela’s economic crisis has forced Marcano, now in her 50s, to abandon her career in public administration and start over in Chile, doing odd jobs. She used to work at the Women’s Ministry — one of the 13 or so ministries established under Chávez, many of which have either merged or suffer from high turnover and staff shortages.

Over time, Marcano says Chávez’s language became radically different, shifting away from socialism to favoritism and loyalty. The system began to value loyalty over merit, giving priority to graduates from colleges started by the revolution, or taking over factories and land with vague, and usually, unfulfilled promises of social redemption. “For me, that wasn’t socialism, but communism in disguise. You simply can’t impose equality by being unequal to others.”

Now, Nicolás Maduro — the man Chávez appointed as his successor on his last public appearance before dying of cancer on March 5, 2013, six years ago Tuesday — is facing a nation plagued by hyperinflation, crumbling infrastructure and armed militias controlling areas within cities and the countryside.

On top of that, an ongoing constitutional crisis has called Maduro’s legitimacy into question. National Assembly speaker Juan Guaidó assumed the role of interim president on Jan. 23, and with the United States, most of the European Union, and a large part of Latin American nations supporting his claim, some say this could be mean not only the end of Maduro but also the Bolivarian Revolution.

‘I’m the Chávez generation’

“I’m the Chávez generation; I lived very little of what was before,” said Andrés, 28, who requested an assumed name to protect his identity. He teaches at a state-run high school in the city of Maracay and is afraid he might lose his job for speaking so candidly about the government.

He encountered what became known as Chavismo when he was in high school and read about the events of April 2002, when Chávez was briefly ousted after a general strike and massive protests in the country’s capital that left dozens dead. For him, the culprits — US-controlled opposition — were clear. “Mind you, I was still a kid,” he said with some hesitation.

“Venezuela continues to be the same oil country that it was in 1999. With Chávez, a lot of myths were created.”

Despite Chavismo promises of building a new society, he admits with some pain that very little has truly changed: “Venezuela continues to be the same oil country that it was in 1999. With Chávez, a lot of myths were created.”

Under Chávez, oil money flowed. With some of the biggest oil reserves in the world, Venezuela has been a reliable oil supplier for the United States since the 1920s, making it one of Latin America’s wealthiest and most stable countries. Despite a dramatic drop in production, according to OPEC, oil sales represent 98 percent of the country’s income.

In the 1970s, the oil industry was nationalized. With a hefty income from prices skyrocketing due to the 1973 Oil Crisis and Arab embargo, the Venezuelan government invested in infrastructure and social programs never seen before, but it also paved the way to widespread corruption and inequality once the prices collapsed in the ’80s.

Thirty years later, during the Iraq War in the early 2000s, oil prices went through the roof again. People from the countryside poured into cities looking for their fair share — ultimately becoming dependent on the state to survive — but the same inequalities and disadvantages persist.

For Andrés, today’s story isn’t so different: “Oil gave us … everything, including this crisis.”

Andrés doesn’t have high hopes for the opposition, either, assured that Maduro will finish his term or at least face a referendum. “I’m sorry to say this to you, but it looks like Maduro is setting the political and strategic trend for the world.”

With over 5.5 million members, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela — the country’s ruling party and the backbone of the Bolivarian Revolution — boasts of being one of the largest political parties in Latin America. But its performance in previous elections has steadily dwindled.

In 2012, Chávez obtained 8.1 million votes, a number the party never managed to surpass. When he died in March 2013, however, an emergency presidential election was held and Maduro obtained 600,000 less. From then on, their turnout kept shrinking, only picking up in the widely contested 2018 presidential elections, where Maduro claims to have obtained 6.2 million.

‘Always loyal, traitor never’

The Bolivarian revolutionary movement still has fervent believers, and one of them is Maracaibo-based journalist Gloria Rivas who puts on her Twitter bio: “Always loyal, traitor never,” a motto recently adopted by Maduro’s government.

“I’m assured that all these problems we are facing have been created by those adverse to the Bolivarian Revolution with the goal of breaking the people’s will.”

“I’m assured that all these problems we are facing have been created by those adverse to the Bolivarian Revolution with the goal of breaking the people’s will,” said Rivas, who proudly adds that she has been supportive of the revolution since 1992 and considers this just the latest step of a “series of putschist [overthrow] attempts.”

For her, the changes that Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution have brought are “endless and beneficial for all the inhabitants of the nation,” and are spearheaded by programs that cover food, health, household and education, among others.

Although some have lauded Chávez’s policies in his early years — such as the eradication of illiteracy and poverty reduction — the past decade has called the results of these achievements into question. Today, 87 percent of Venezuelans are poor while 61 percent live in extreme poverty, according to ENCOI, a living conditions survey conducted in 2017.

So, what was Chávez’s most significant contribution?

“The class consciousness [awakened] in the Venezuelan people by the Comandante Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías,” Rivas said.

She believes there’s no difference between Chávez and Maduro — she thinks that the latter is simply continuing the work set by Chávez. In her view, the people and the revolution will inevitably vanquish all these attacks by what she calls the “gringo [yankee] empire” (referring to the US) and describes Guaidó as an “impostor” and a “madman.”

“[Guaidó’s] name will go down in history as the biggest traitor to the nation any country has ever had.”

Rivas says the current threat of a US military intervention is confirmation of a conflict that the Bolivarian Revolution anticipated for many years. After the Jan. 23 events, videos on pro-Maduro media began depicting him in military exercises, surrounded by men and women in fatigues and awaiting the upcoming battle.

But not everyone who supports the Bolivarian Revolution supports Maduro. In the past few years, dissident movements of Non-Madurista Chavistas, or “Foundational Chavistas,” have grown in importance, and opposition leaders have reached out to them with invites to rallies and public events to show that moderate Chavistas can exist in a postrevolutionary Venezuela.

There’s a lot of bad blood against former supporters who have distanced themselves from the Bolivarian Revolution. They face rejection by most opposition followers — including a great chunk of the country’s 3 million diaspora — who blame them for once supporting policies that spurred the current crisis. There are Facebook pages and Twitter accounts dedicated to publicly outing them.

But their status as “traitors of the revolution” also means they aren’t exactly welcomed by die-hard loyalists of Maduro.

Marcano, now in Chile, has lost faith in the Bolivarian Revolution, but she doesn’t consider some of the opposition’s latest actions quite legal, either. It’s no better than Maduro’s actions in recent years, she says — like naming 13 new justices to the Supreme Court in a single day back in 2015, to avoid letting an opposition-led legislature designate the next 12-year term.

If Venezuela’s current political situation gives way to a transitional government, Venezuelans will have a long, tortuous path that might bring about national reconciliation.

Until then, the stigma of having believed in the Bolivarian Revolution — those who many blame for the country’s ongoing disaster — will continue to cause divisions for years to come.