You can take selfies with once-secret KGB spycraft at this NY museum

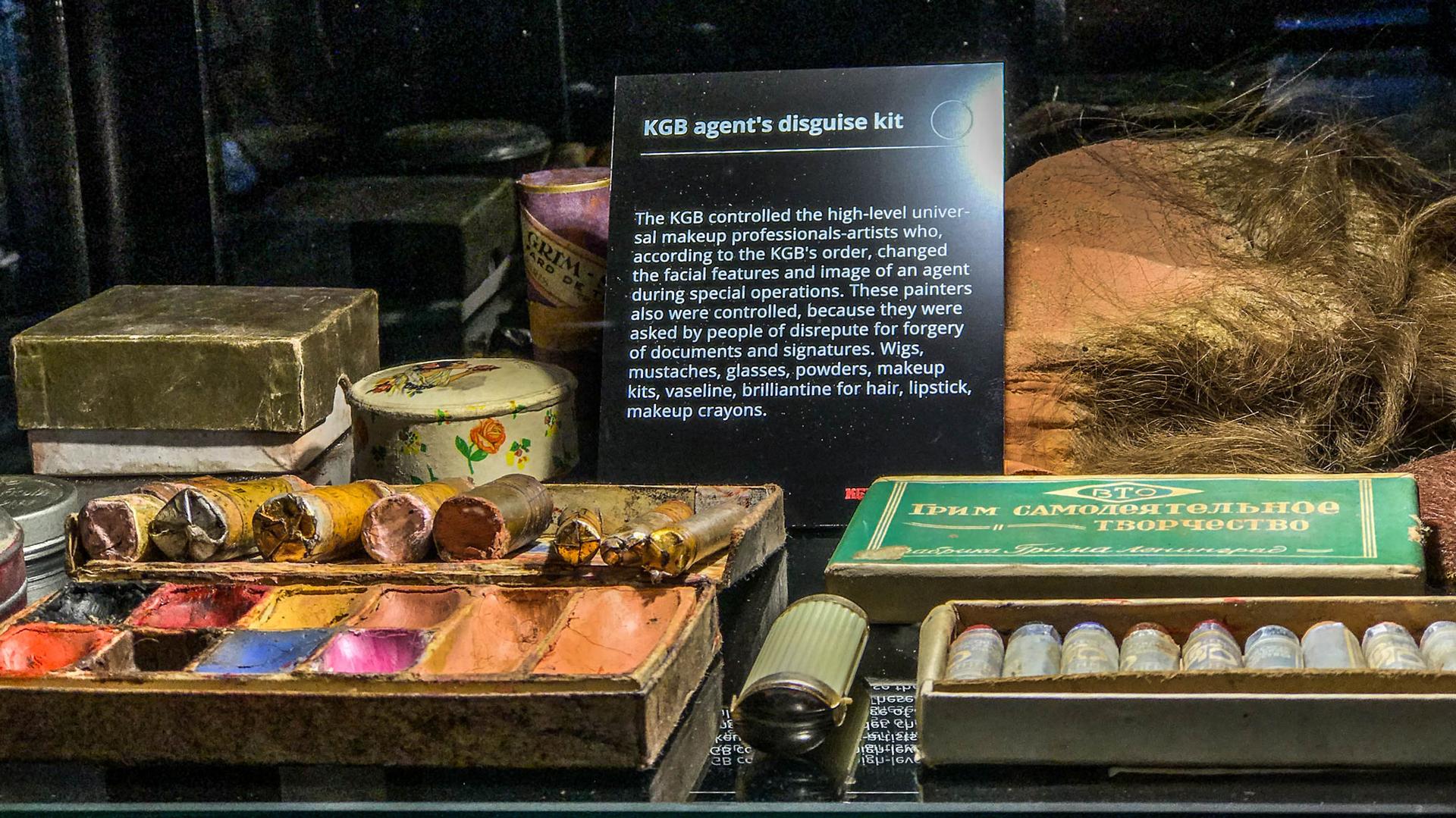

A KGB agent disguise kit. In the Soviet era, master make-up artists were just as sought after by the secret police as optical specialists and cryptologists.

It’s been almost 30 years since the KGB officially ceased to exist, and yet its name remains as synonymous with spycraft as that of James Bond’s.

Aside from a few Cold War flare-ups, a handful of high-profile assassinations and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s well-documented time in the KGB, what do we really know about the Soviet regime’s infamously brutal secret police? Not a lot.

This isn’t surprising: The KGB guarded the tools of its trade with the same ferocity as the nation’s nuclear secrets. But now, some of the esoteric secrets of the Soviet secret police are on display in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

The KGB Spy Museum is the brainchild of Julius Urbaitis, a lifelong collector of historic military paraphernalia and his daughter Agne Urbaityte, who identifies herself as a “secret telephone communications and cipher machines expert.” The father-daughter duo opened their first museum five years ago in an atomic bunker in Kaunas, Lithuania, but the New York offshoot, Julius says, is far larger and more comprehensive; many of the artifacts on display have never been available to the general public.

James Bond fans will find much to delight in here. The museum is filled with dramatic set pieces; a KGB office with a safe stuffed with Soviet-era rubles to pay off spies, a pair of authentic prison doors and 40s-era NKVD (the precursor to the KGB) trench coats available for selfies.

Despite the veneer of Soviet kitsch, Kremlinologists and serious historians won’t be disappointed. After the Soviet Union fell apart and Russia went into economic freefall in the 1990s, the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, (soon re-branded as the Federal Security Service, or FSB in Russian) fell into disarray.

At the same time, espionage was moving online and the digital revolution quickly rendering engineering marvels like cufflink cameras obsolete. Urbaitis spent years hunting defunct Communist spy technology and ephemera; knocking on doors, following leads and building a rolodex of trusted contacts. And, just like a true KGB officer, he had to become adept at recognizing a true artifact from an imposter; of the more than 3,500 artifacts on display at the museum, only two are reproductions.

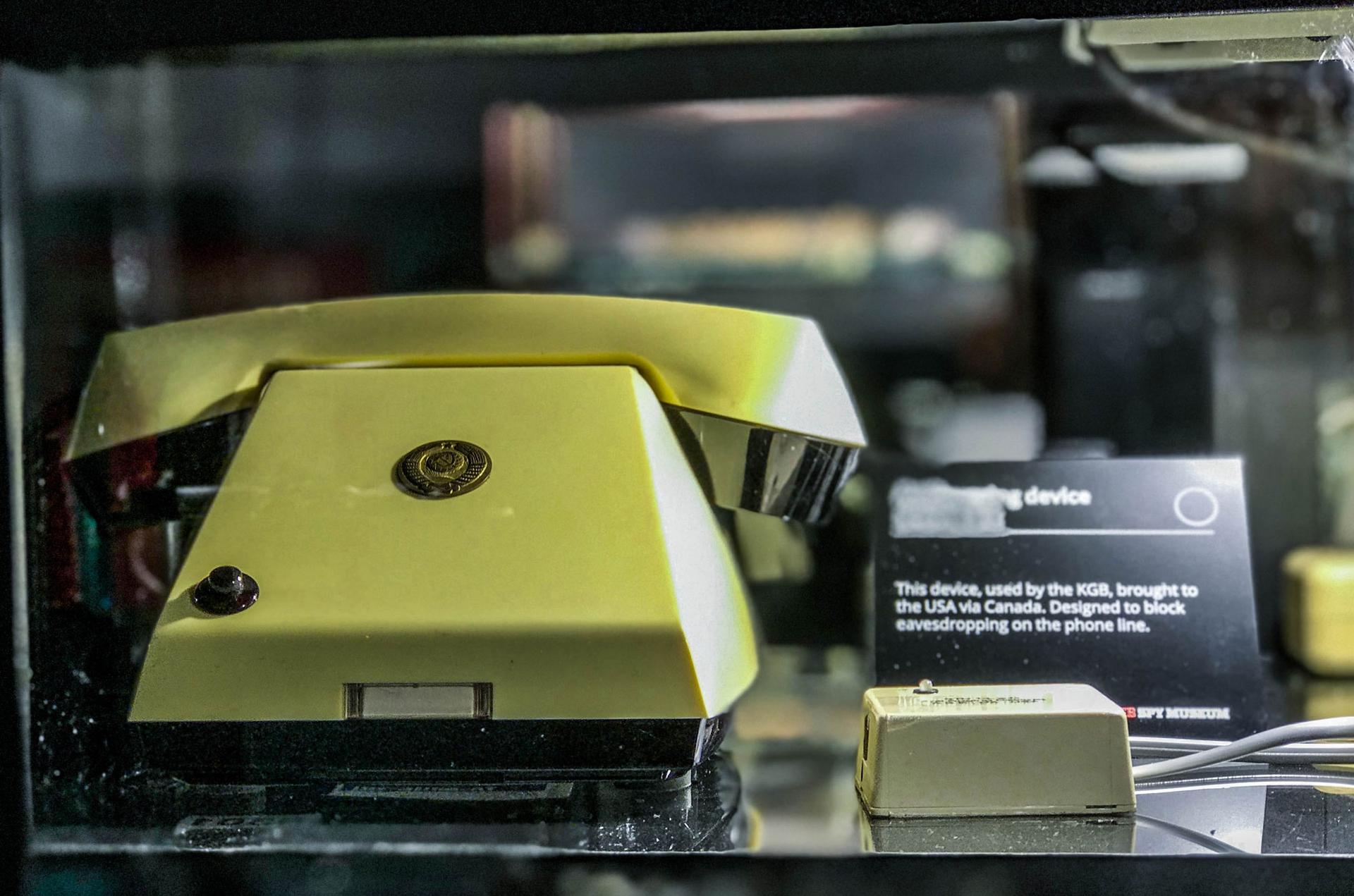

The museum pays homage to this bygone analog era, revealing the Wozniak-level of wizardry that enabled the KGB’s work. These impossibly intricate Cold War listening devices and hidden cameras — ingeniously disguised and impeccably crafted — also function as works of art, even when the mission was murder.

Admiring these tiny, sometimes macabre, creations, it’s easy to forget what’s not on display here — the KGB’s real cudgel, after all, was psychological. The Soviet regime managed to weaponize an entire population by wreathing them in paranoia. Soviet citizens always had to ask themselves: Who’s listening when I speak? Who’s watching?

The KGB Spy Museum is located at 245 West 14th St. in New York City and is open 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily.