American evangelicals are more diverse than ever. But some don’t want to be part of the ‘evangelical movement.’

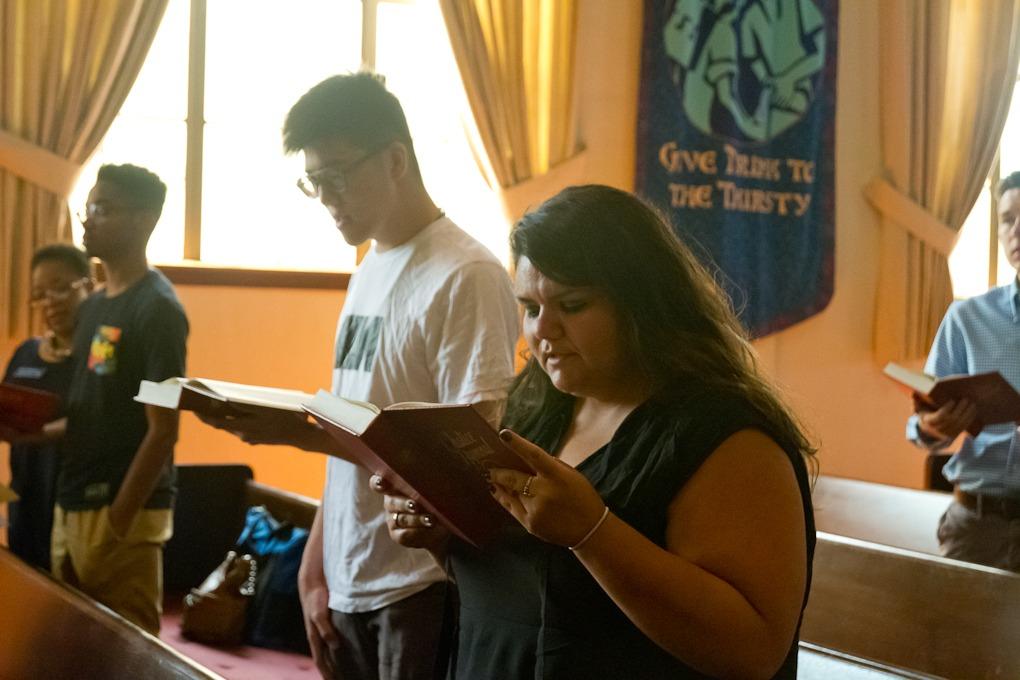

Pastor Liliana Da Valle sings with her congregation at Grace Baptist Church on June 3, 2018 in San Jose, California. The church has become increasingly racially diverse in the last three years.

For the past three years, Pastor Liliana Da Valle has watched the small congregation of Grace Baptist Church in downtown San Jose become increasingly diverse.

“A woman with an accent is preaching and all of a sudden people know, ‘If this is a church where they have a pastor with an accent, then they will receive me,’” says Da Valle, who immigrated from Argentina to the US 36 years ago.

Not only has her church attracted more Latinos, it has also drawn Asians, many of them students at nearby San Jose State University.

An increasing number of Latinos and Asians identify as evangelical Christians across the US, even as the ranks of American evangelicals are shrinking overall. People who self-identify as evangelical or born-again Christians make up 26 percent of all Americans. Seventeen percent of white Americans identify as evangelicals, compared with 23 percent in 2006, according to a survey by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI).

After the 2016 election, University of Maryland Asian American studies professor Janelle Wong wondered if the increasing diversity in evangelical Christianity might change its politics. White evangelical Christians overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and continue to support the president’s policies, according to PRRI.

Together, Asians and Latinos make up about 13 percent of all evangelical Christians in the US. Some convert after arriving in the US, although evangelical Christianity is also gaining popularity in Latin America and some Asian nations, such as Korea and the Philippines.

“These groups represent a source of growth. Will they totally change the Christian right or will they add to their power?” Wong asked.

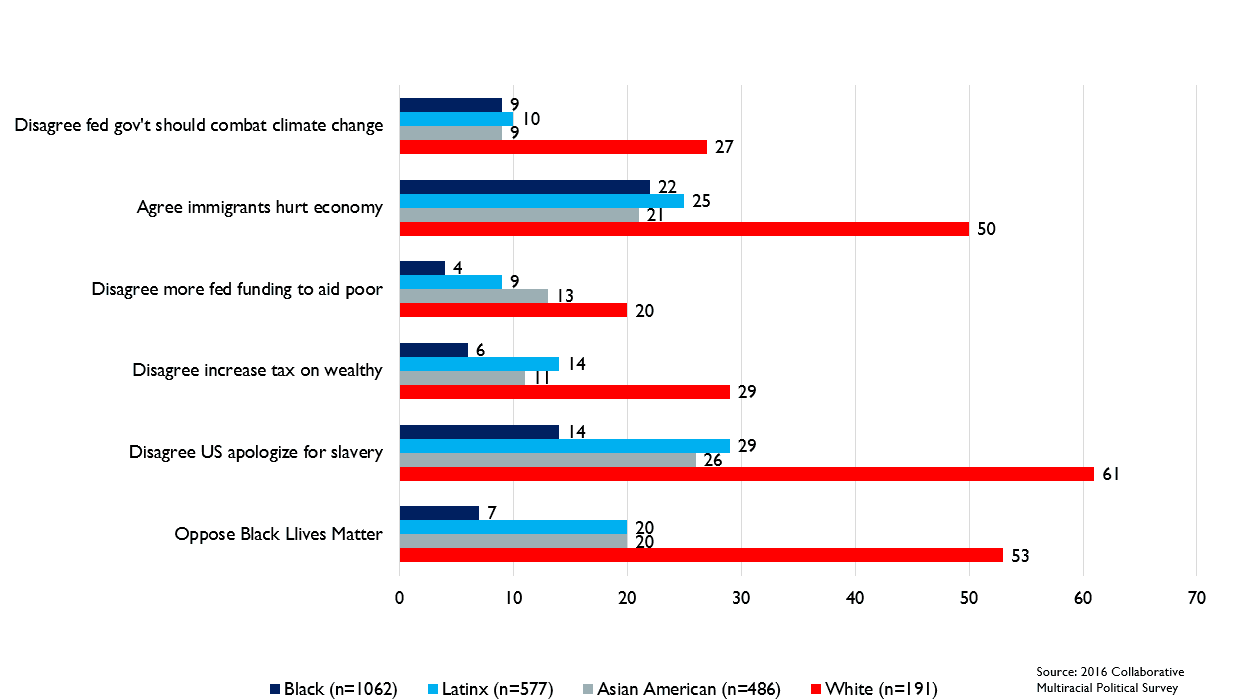

So she conducted a nationwide survey and visited more than 50 churches in the Houston and Los Angeles areas. Wong and her team found that politically, non-white evangelicals tend to have very different views than white evangelicals.

But she also found that their divergence was not necessarily changing the political views of others in their churches.

“[There is] no doubt that Latinos and Asians are going to be a growing part of different religious communities, including the evangelical church, and their politics will look different than in the white evangelical space,” Wong says. “But there are serious barriers to their political empowerment similar to those progressive white evangelicals face.”

Unlike Republicans, says Wong, the Democratic party does not usually try to persuade voters that its platform is in-line with Christian teachings.

The results of her study are published in a book, “Immigrants, Evangelicals, and Politics in an Era of Demographic Change.”

In contrast to their white, American-born counterparts, non-white evangelicals are much more progressive on many issues, such as immigration, the environment and social services. While half of white evangelicals believe that immigrants hurt the economy, only 22 percent of black, 25 percent of Latino, and 21 percent of Asian evangelicals agree.

According to another PRRI survey released in June, most religious groups — including non-white evangelicals — are opposed to laws that would prohibit refugees from entering the US. However, white evangelicals are roughly split on this topic. Eighty-seven percent of non-white Protestants are opposed to the separations of undocumented children from their parents at the border; among white evangelicals, 51 percent are opposed to the separations.

More: Some evangelicals are speaking out in favor of DACA recipients

At Grace Baptist, which is part of the American Baptist denomination of Christianity, Da Valle says they talk about political issues, just not political parties or candidates.

“We talk about racism, we talk about gay marriage, any political issue. We talk a lot about gun violence right now,” Da Valle says.

The church offers shelter and classes for homeless people, and it has declared itself a sanctuary church where undocumented immigrants can seek refuge from deportation, although no one has yet used the service. Da Valle is careful to clarify that she, like many Latinos, thinks that being evangelical is about religious beliefs, and not the voting bloc that has been aligned with Republican politics since the 1960s.

Also: A black church in Boston says it’s called to be a sanctuary

“For the white Americans, ‘evangelical’ has to do with the evangelical movement,” Da Valle says.

For Latinos unfamiliar with the politics of the US, “‘evangelical’ means something different. It means that we are Christ-centered. It’s not about the movement.”

Some Christians are distancing themselves from the term “evangelical” even if their beliefs remain unchanged. It is difficult to concretely define evangelical Christianity because it is not an official religious group. Some mainline denominations, such as Baptists, are often considered evangelical, but many evangelical churches are unaffiliated with a national organization. In popular culture, the term “evangelical” is often associated with certain cultural touchstones — purity rings, televangelists or Republican politics. But religious scholars generally define evangelical as referring to reliance on the Bible, a belief in Jesus Christ as redeemer, conversion through a born-again experience, and the sharing of one’s faith through missionary activities.

In one area, for example, Grace Baptist itself diverges from most other evangelical churches: Rainbow banners on the front of the building announce that the church embraces the LGBTQ community.

“The church is fully welcoming and affirming,” Da Valle says. “Our associate pastor is gay and married.”

According to Wong’s study, black and Latino evangelical Christians are similar to their white peers when it comes to gay marriage; over half oppose it. Asian evangelicals are the exception, with only 30 percent in favor of banning same-sex marriage. When it comes to abortion, black and Asian evangelicals are slightly more liberal than whites, while Latinos are slightly more conservative than any other evangelical group, with 76 percent opposed to unrestricted, legal abortion.

Da Valle says this conservative strain among Latino Christians has driven her four adult children — including one son who is gay — away from all-Latino congregations.

Russell Jeung, a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University, says that gay marriage has also been a catalyzing issue for some Asian congregations.

“A lot of Chinese and Korean churches participated in mass demonstrations for Prop. 8, California’s 2008 ballot initiative that attempted to ban gay marriage,” Jeung says. “These same constituencies would probably be against affirmative action, as they highly value family and a strong work ethic. They see affirmative action as undermining a meritocratic system.”

More than 50 years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called Sunday mornings the “most segregated hour in this nation,” Wong and her team of researchers discovered that most Christians still attend churches with people of their own race. And even in multiracial congregations, race is not often the focus of sermons from the pulpit.

More likely, race might be a conversation at a small group meeting, and when the subject comes up it usually has to do with personal relationships or spiritual pursuits.

“People can actually interact with people of different groups but still hold on to more conservative attitudes,” Wong says.

Kim Chew of Pleasanton, a city in the easternmost reaches of the Bay Area, considers herself an evangelical Christian and a Republican. She’s the grandchild of immigrants from China and attends a Bible-based church. While the congregation is ethnically diverse — with Chinese, Korean and Indian congregants — it leans conservative.

“No matter your sexuality, you are still welcomed and loved,” she says. “But we call sin ‘sin.’”

She blames the media for perpetuating a misconception that “evangelicals and Christians are people who are narrow-minded, who are righteous and unloving. You don’t hear about the compassion, the caring for people, the food pantries, hospitals and orphanages started by Christians.”

Even in her conservative church, she says some people are moving away from the term “evangelical,” preferring to call themselves followers of Christ.

And even in congregations whose members are both racially diverse and politically progressive, such as Grace Baptist Church, the practices still look like those of a white church. Da Valle is not the first person of color to lead Grace Baptist; the church had a black minister in the 1980s.

At the other end of the San Francisco Bay, in Berkeley, Church Without Walls operates differently. The congregation is largely white and Asian American. Ten years ago, the church started a Spanish-language service. While many of the members are bilingual in English and Korean or Mandarin, the Latino congregants were more recent immigrants and tended to speak only Spanish.

However, Pastor Gary VanderPol believes the biggest challenge wasn’t race. It was the financial divide between the Latino worshippers and their white and Asian counterparts.

“Berkeley is one of the most liberal cities in America,” VanderPol says. “There’s all this rhetoric about welcoming immigrants and refugees but none of them can afford [to live here].”

Church Without Walls recently ended its Spanish-language services because the worshippers it served were leaving Berkeley because of the rising cost of living. VanderPol says most of the whites and Asians who remain in the church are American-born and college-educated, which helps them to afford to live in the Bay Area.

Although many Church Without Walls members are not comfortable calling themselves “evangelicals,” the congregation still is part of the Evangelical Covenant Church denomination. Nationally, that organization has shifted from its predominantly white and Swedish roots to become multiethnic in membership, as well as leadership.

“They actively embraced the racial reconciliation movement of the 1990s,” Jeung says, referring to the teachings of Dr. John Perkins who preached that wealthier, white Christians should move to poorer urban areas to so their resources could be shared with communities of color.

“To become multiethnic, you need to have multiethnic leadership, and the face of the organization has to be multiethnic,” Jeung explains.

Da Valle, too, says that Christian leadership needs to become more diverse — she wrote a doctoral thesis on multicultural ministry while in seminary. Every Sunday, she preaches from the pulpit, but also tries to infuse her ministry with more of a Latin style, such as walking around to greet worshippers and singing from the pews.

However, the changing face of evangelical Christianity does not necessarily mean a shift in its political soul.

“There is very little evidence that anything, even images of children being separated at the border from their parents, will change the political perspectives of rank-and-file white evangelicals,” Wong says.