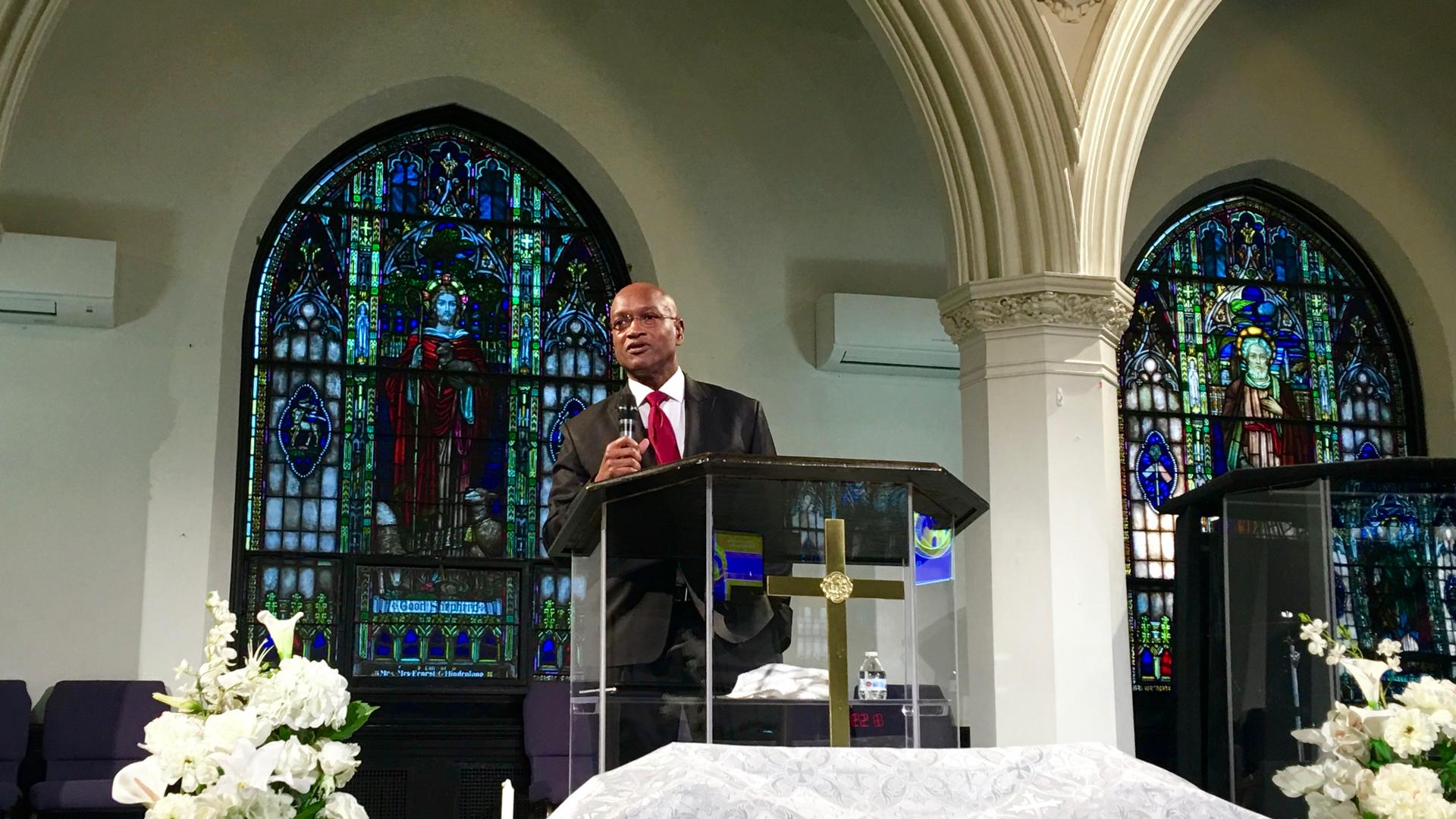

Rev. Ray Hammond says Bethel AME Church really has no choice but to provide sanctuary for an undocumented immigrant from El Salvador.

First-time visitors to Sunday morning services at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston are met with smiles, handshakes and even hugs. To call it a warm welcome would be an understatement.

Bethel AME is no stranger to political activism. But the mostly African American congregation has taken up a new mission. In late September, the parish decided to give shelter to a man from El Salvador facing deportation.

Church officials turned down a request for a face-to-face interview with the man, a father of five, who’s now living at Bethel AME. But Rev. Ray Hammond explained the church's thinking behind becoming a sanctuary church.

“This is not a political issue. Ultimately it's a human issue,” says Hammond, who co-founded Bethel AME with his wife, Gloria White-Hammond, a fellow physician and pastor herself. The couple started the church in 1989. It has done work on various social justice issues, including with youth, prisoners and the impoverished.

“For a number of years, we've been concerned about the immigration crisis in our country,” Hammond says. “We've been deeply concerned about the way in which the immigration issue — rather than being dealt with honestly, openly, justly, humanely — has become increasingly a political football.”

Hammond says he was a little surprised at how much support there was among congregants for taking this latest step.

“I expected perhaps more opposition. Historically, sometimes there has been tension between the African American and Latino community, between what African Americans see as ‘native-born’ versus ‘immigrant,’” Hammond says.

A couple members of the congregation expressed some doubts about giving shelter to someone at risk of being deported, Hammond adds. But that was about it.

“The vote was almost unanimous to support it. And people certainly wanted to understand the protocols and how we're going to make sure that this work. But the support was overwhelming,” Hammond says.

It’s not clear what legal options remain for the man facing deportation. A request to interview his lawyer was declined.

A spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement also turned down an invitation to speak on the record, but on background he pointed to guidelines put in place by previous administrations that prohibit federal agents from entering sensitive locations to make arrests, such as churches, schools or hospitals, under most circumstances.

Still, the ICE spokesman said that churches giving sanctuary to someone with a deportation order might be committing a felony offense by harboring a fugitive.

The Trump administration appears to be targeting sanctuary, jurisdictions that limit local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

Over four days in late September, federal agents conducted a national operation inside 10 sanctuary cities, arresting nearly 500 people, including 50 in the Boston area.

The acting director of ICE, Tom Homan said in a news release that sanctuary cities, “are shielding criminal aliens from immigration enforcement and creating a magnet for illegal immigration. As a result, ICE is forced to dedicate more resources to conduct at-large arrests in these communities.”

Bethel AME is not acting alone. It's part of a coalition of three local churches and three synagogues, all contributing to the effort to provide sanctuary for the undocumented man from El Salvador. At least one other church in the Boston area has declared itself as a sanctuary.

Over the summer, University Lutheran Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said it was providing shelter to a woman from Ecuador, along with her two children, who feared deportation.

Religious leaders are busy working on what comes next. Last week, clergy from several different faith traditions met at St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral in downtown Boston to sing, pray and talk about how their communities might be willing to respond to what some see as a looming crackdown on immigration.

People see this issue as a fight for the nation’s soul, says Rev. Arrington Chambliss, a priest with Episcopal City Mission in Boston.

“Words without action are empty,” Chambliss says.

“We’re in a particular moment in our history,” she adds. “There is a very pernicious and focused threat on particular communities.”

“It’s not trying to be in conflict with anyone, but it’s being instead in deep relationship with our neighbor.”