For a child migrant, days feel like a lifetime when you’re imprisoned and alone

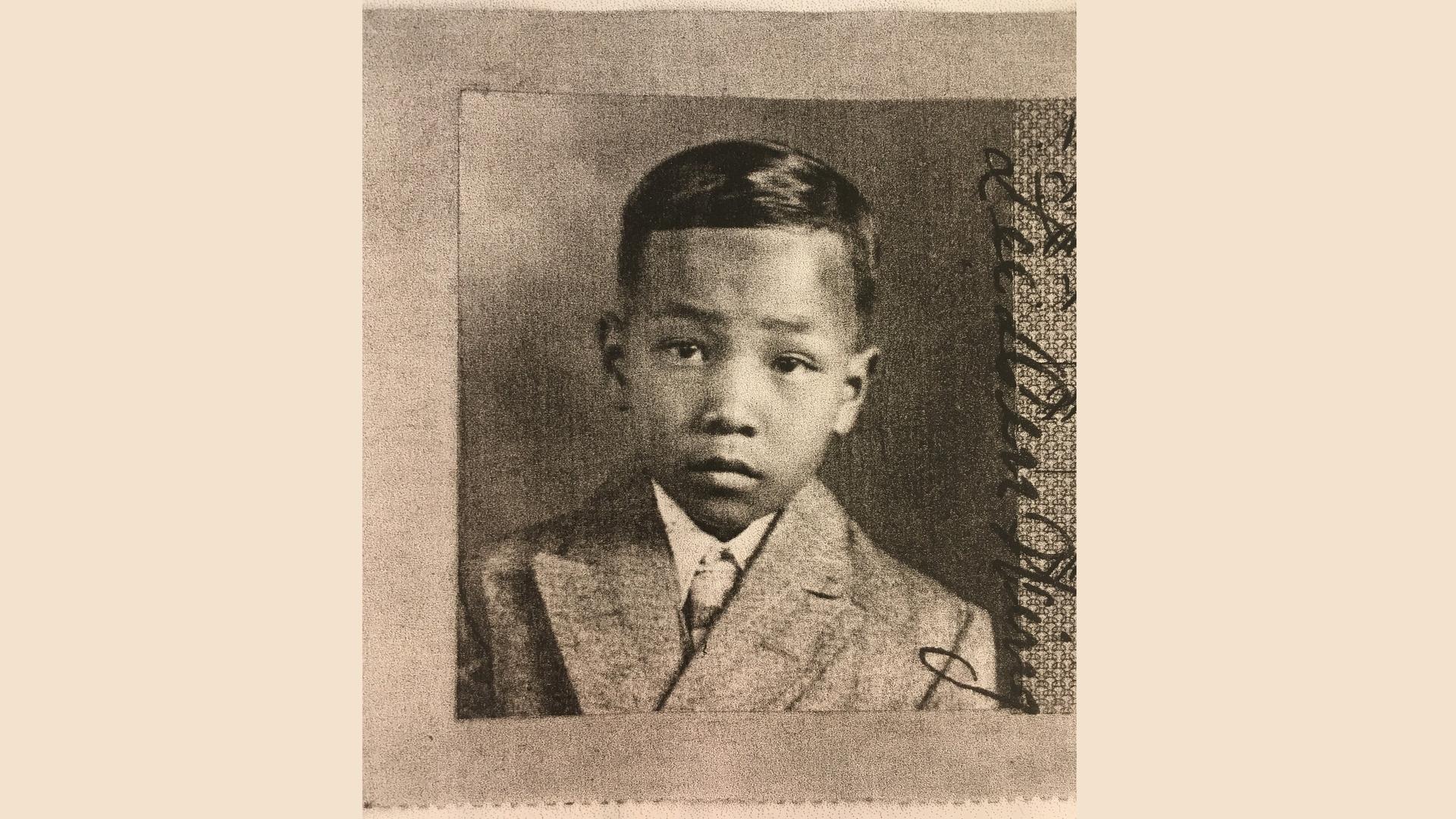

Lew Din Wing arrived in the US in 1930 at 9 years old. He was separated from his family and sent to Angel Island Immigration Station.

At 9 years old, my grandfather Lew Din Wing was separated from his family and placed in immigration detention.

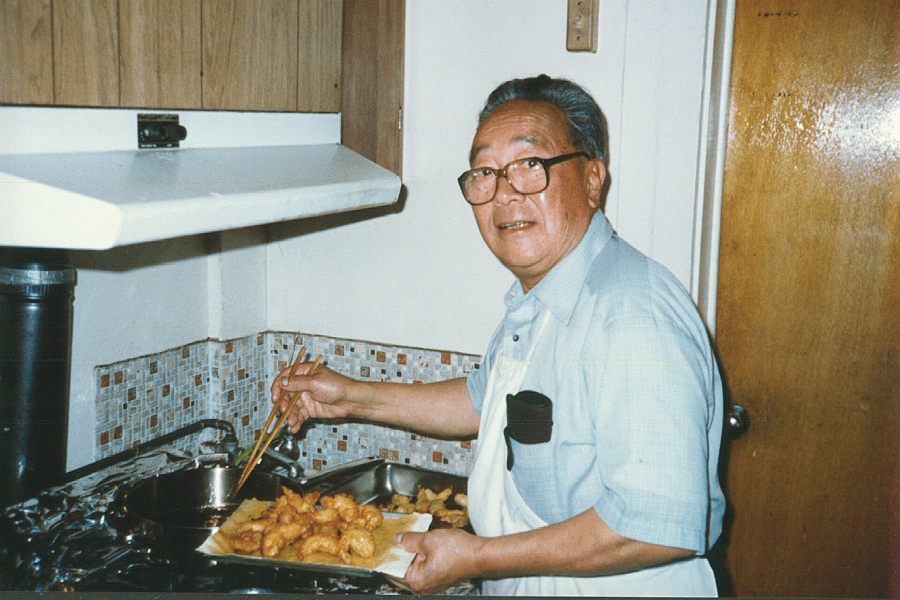

In 2002, I went to visit YeYe in his San Francisco apartment and I brought a tape recorder with me. He told me about his experience in detention in the last conversation we had before he died. Now, 16 years later, I can still listen to his voice, his labored breathing, and his life story. Or at least I can listen to the story he wanted to live on.

Born in China, YeYe had crossed the Pacific with his older brother in 1930 to join their father who was living in San Francisco. But when he arrived, US officials refused to allow YeYe to land and instead sent him to Angel Island Immigration Station.

There he was detained, interrogated and denied any contact with his family. At the time, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred the entry of working-class Chinese immigrants like my grandfather. No explict policy demanded that families be separated. Nevertheless, officials routinely kept family members apart because they wanted to prevent them from coordinating their answers before they faced interrogation.

YeYe remembered being the youngest child in the male detention center, sleeping at the bottom of a bunk bed stacked three high and heading for the cafeteria at the sound of a bell. Tensions were high among the detainees. He witnessed fights and heard rumors about men who had committed suicide. When his father tried to send him a little extra food, it was quickly stolen. If you’re smaller, he told me, “you can’t do nothing.”

Hear Lew Din Wing recall what it was like to be in immigration detention as a child.

YeYe failed his first interrogation. Standing before the immigration board without a family member or a lawyer present, he made a couple of mistakes on the dozens of questions he was asked. Decades later, he told me, “I was one of the unlucky ones who stayed 9 to 12 months — I don’t even know how long.”

A few years after he passed away, I requested Lew Din Wing’s “alien” file from the Department of Homeland Security and, flipping through the paperwork, learned that he had actually been detained for just 34 days.

Thirty-four days is a lifetime when you’re 9 years old and imprisoned all alone.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my grandfather as I watch the Trump administration’s “zero-tolerance policy” in effect at the southern border. Government officials say that more than 2,000 children have been separated from their families in just six weeks of the new immigration policy’s full implementation. Family separation at the border has been happening for a long time, but the sudden increase in scale is appalling.

In my final conversation with my grandfather, there came a point when he told me to turn the tape recorder off. He wanted to tell me the other part of the story, the part that involved unlawful entry and an undocumented life.

When he arrived in the San Francisco Bay, YeYe was too young to understand the United States’ discriminatory immigration laws that barred Chinese immigrants based on their race. His father, who had already entered the country unlawfully, bought him a one-way ticket across the Pacific and YeYe simply climbed aboard. Today, we might call him a “Dreamer.”

A week from death, YeYe still held the trauma of immigration detention, made all the more acute by the fear that it had been deserved. He had lived in the US for the previous 72 years, fought for America in World War II, and raised American children and grandchildren. Still, the childhood wound had never closed.

As I watch Trump’s immigration policy separating thousands of children from their parents, of course I see the faces of my own children and imagine what they would suffer.

But I also see the face of an old man who still held that pain.

Beth Lew-Williams is an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and author of “The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America.”