Long before anxiety about Muslims, Americans feared the ‘yellow peril’ of Chinese immigration

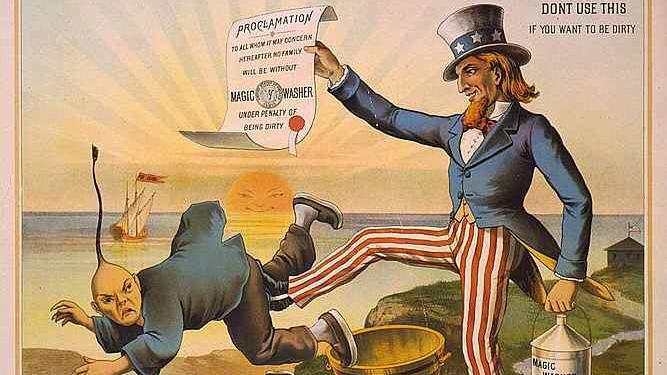

A soap advertisement from the 1880s, sub-titled 'The Chinese Must Go'

Donald Trump’s proposal to ban an entire class of people from entering the United States is not without precedent.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned all Chinese from coming to America, with a handful of exceptions: merchants, teachers, students, travelers and diplomats.

“This is the first time in US history,” says Professor Erika Lee, director of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, “that we single out a group for exclusion based on their race, and also based on class. But it would not be the last.”

Later, the ban was extended to cover all ethnic Chinese, wherever they hailed from. Then later still, pretty much all Asians were banned.

“It may be hard for people to understand, or even believe,” says Lee, “because today, Chinese Americans, and Asian Americans in general, have a stereotype of being the model minority in the United States. But a century ago, Chinese and other Asian immigrants were seen as the opposite of what America wanted. In fact, so dangerous to American society, the American economy, that the United States really needed to ban all of them from coming into the country.”

The Exclusion Act of 1882 was very popular. Pressure came from workers’ groups who were afraid that Chinese laborers were undercutting wages. More pressure came from racial theorists who feared that America would be literally overrun with Chinese. There was a bipartisan effort in Congress to over-turn a veto from President Chester A. Arthur.The atmosphere became toxic for Chinese Americans.

“This is the beginning of what Chinese in America call the reign of terror,” says Lee, because it legitimized discrimination. “[It’s] a period where there’s no integration. They’re banned from becoming naturalized citizens as well. They create an underground economy and shadow society. It’s really bound to the confines of ethnic Chinatowns. There’s informal segregation that bans Chinese from moving into certain areas. There’s formal discrimination banning them from certain occupations. There’s anti-miscegenation laws.”

Lee’s own family lived through this era. “My great-great-great-grandfather was one of those first Chinese men who came, seeking gold, in 1854, in California. And because of the anti-Chinese sentiment, and because of the Chinese exclusion laws, he never brought his own family over to the United States. So for three generations, my family was split across the Pacific Ocean, with the women and children living in China. And the men — first my great-great-great-grandfather, and then his son, and then his son — coming to the United States to run some businesses.”

“It wasn’t until the early 20th century,” adds Lee, “when my grandparents, on both sides, were immigrants during this time period. And when they entered the country during the exclusion era they went through all sorts of processing and identification and interrogations and detention.”

“It’s a history that quite frankly Chinese Americans are still trying to heal from,” says Lee. “So these proposals to ban another group really strike a chord with us today.”

The Exclusion Acts were not repealed until 1943, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt pushed Congress into action to cement America’s World War II alliance with China against the Empire of Japan. Roosevelt described the laws as an “historic mistake.”

“As a historian,” Lee concludes, “I try to think about the ways in which we as a country can learn from the mistakes of the past, and perhaps use our history to illuminate complicated issues, and make sure that we can move forward in the right way. I never thought I would stand before my students — like I did yesterday — and say that the current immigration proposals make the egregious Chinese Exclusion Act … look better than what we’re talking about today.”

Historian Erika Lee is director of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, and author of a new book called ‘The Making of Asian America.’