Family separation under ‘zero-tolerance’ policy could leave lasting trauma in children, pediatric doctor says

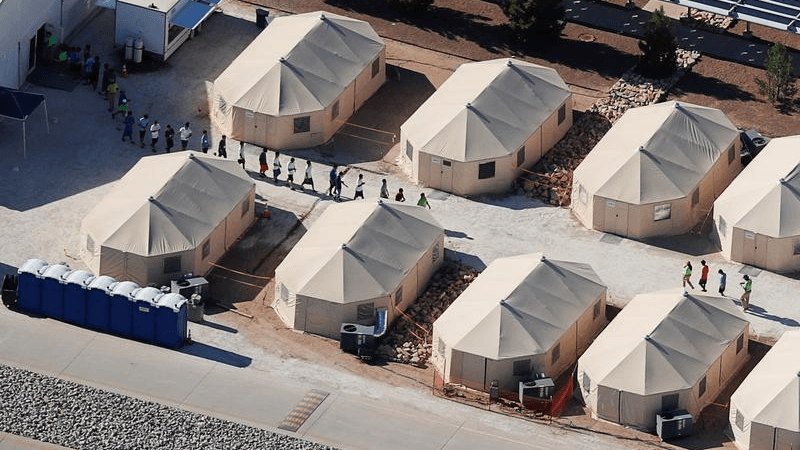

Immigrant children, many of whom have been separated from their parents under a new “zero-tolerance” policy by the Trump administration, are shown walking in single file between tents in their compound next to the Mexican border in Tornillo, Texas, June 18, 2018.

Migrant children who suffer trauma as a result of being taken from their parents at the US-Mexico border may never fully recover, according to a pediatric doctor who recently visited a shelter where such children are being held.

The Trump administration’s “zero-tolerance” immigration policy — in particular, its practice of separating children from their migrant parents or guardians as they are caught trying to enter the US illegally — has come under fire in recent days.

Last week, government officials said that from April 19 through the end of May, nearly 2,000 children have been separated from adults who were either their parents or guardians. Furthermore, 658 children were separated from 638 parents between May 6-19 alone, according to a US Customs and Border Protection official. Most come from Central America.

Despite President Donald Trump himself, Homeland Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen and Attorney General Jeff Sessions reaffirming their approval of the policy Monday, Democrats and Republicans alike have made this a bipartisan concern. Republicans in the House of Representatives are working on a “compromise” immigration bill that would modify the current policy by ensuring children would be held in the same facility as their parents or guardians if they are detained. (If passed, it may have the effect of holding both in detention for longer.) Currently, children and parents are kept in separate facilities.

But children can suffer irrevocable, long-term trauma even from a short-term separation from their parents, says Dr. Colleen Kraft, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Kraft says she recently visited a detention center that held unaccompanied migrant children separated from their parents at the border. It’s overseen by the federal Office for Refugee Resettlement, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. When she first entered the building, Kraft was led into the toddler room, which was filled with children ranging in age from 18 months to three years. She recalls one girl crying hysterically on the mats in the middle of the room.

“The staff were by her, but they weren’t allowed to hold her, comfort her,” Kraft says. “So she was just crying and wailing. Her little arms and legs were just pounding, and she was inconsolable. And we all knew why. We knew that she had been taken from her mother, and she wanted her mother.”

Positive versus toxic

Kraft says the response of the brain to these kinds of stressors such as these has already been scientifically measured.

There are two kinds of stress, Kraft explains: positive and toxic.

Positive stress is very brief in nature. A classic example, Kraft says, is when a child has a temper tantrum.

“What happens in their body and in their brain is that their inflammatory markers, their fight-or-flight hormones, rise. And then in the presence of an adult who can be caring and comforting, they fall and they’re redirected, and the brain actually becomes resilient from that type of stress interaction,” she says. “And we know that only happens in the presence of a loving and caring adult for a young child.”

On the other hand, the separation of children from their parents causes a toxic stress, prompting the same fight-or-flight hormones. But in this case, the stress is dangerous, and the damage can be long-lasting.

“Without that parent to help buffer that reaction, these chemicals go on to destroy the architecture of that child’s developing brain,” Kraft says. “They destroy the synapses that occur that result in the ability for that child to love, to learn, to develop. So separation even for a short time is something that’s toxic to a child’s developing brain.”

Such toxic stress can also cause developmental delays that may reflect characteristics of the autism spectrum — as well as delays as of speech/language skills and gross motor skills, she says. These same children can have increased likelihood of heart disease, obesity, cancer and rheumatoid arthritis.

And there are even broader implications, Kraft says.

“What happens is that overall, this toxic stress really robs these children of the ability to love and to learn and to do well in school and to graduate from high school and to go on to college and to be successful,” Kraft says. “And later on in life, it robs them of their capacity to be healthy grown adults.”

Similar to the girl Kraft mentioned, many of the children being separated from their parents are extremely young — within a few months to three years of age. It is during this early stage, Kraft says, that children are the most susceptible to toxic stress: their brain is building at its most rapid rate as billions of synapses make connections to each other.

“In [that] group, if a child is exposed to love, these synapses for learning, for language, for love become very strong, and what gets pruned away later on are the bad experiences, the upsets, the fear, the anxiety,” Kraft says. “In children who grow up with toxic stress, they never make those connections. And what stays and remains are anxiety, are fear, are other difficulties that go on to really rob that child of the ability to grow into a healthy adult.”

Kraft says children who have experienced such situations — many of whom are now in the US foster care system — have responded to well a form of treatment known as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy.

Of course, she adds, that involves undoing trauma that could have been avoided.

“There are things we can do for these kids,” she says. “But it it’s much easier to build a strong child than to repair a child who’s had this type of damage.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on The Takeaway.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?