She escaped violence in El Salvador, but there’s little time or resources to heal while seeking asylum in the US

Yocelyn is trying to seek asylum in the US after being raped by a gang in El Salvador. She arrived at the border in 2016 and her immigration court date is in April 2018. In the meantime, she takes the bus to work — though she does not have work authorization.

Yocelyn’s 18-month-old has chickenpox. Her younger brother, who is 21, caught it too.

“I take the kids to the doctor because they have Medi-Cal, but we have to put up with it if we get sick,” she says.

Medi-Cal, California’s insurance for low-income families, covers children regardless of their immigration status but only provides coverage to undocumented adults in specific, often extraordinary, circumstances. Yocelyn’s brother has had a high fever for two days.

She tries to give her weeping toddler a spoonful of acetaminophen syrup to ease the symptoms of varisela, chickenpox.

Yocelyn is undocumented, but she didn’t cross the border illegally when she arrived on foot in Nogales, Arizona, in 2016. She waited in line at the port with everyone else trying to cross the border. When her turn came, she asked the US agent for asylum, her 6-month-old baby in her arms, three children and her brother standing by her side.

She is among more than 17,000 people from El Salvador with cases pending in California immigration courts. In the Los Angeles immigration court, where her case will be heard, there are almost 65,000 pending cases, about a tenth of the cases in the queue nationally. It takes almost two years to see a judge, according to government data collected by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). In the meantime, Yocelyn has to make a living, take care of her children and find a way to navigate the complexities of an immigration system that is trying to deport her. And she has to do it all without access to public services that might help her deal with the trauma of the violence she fled in the first place.

There are organizations and state programs that try to support asylum seekers like Yocelyn with counseling, health care and housing, but a draft memo leaked to Reuters indicates that the Trump administration is considering new regulations that make receiving public benefits — even when it’s related to child care, health care or food assistance — a barrier to receiving permanent residence in the US. Advocates says that even talking about that possibility scares people. The suggestion that immigrants should not be receiving help from the government could mean fewer immigrants, especially low- and middle-income people, seek the services to which they are legally entitled and need.

Yocelyn says she doesn’t ask for money or food from the government. She explains in Spanish — she doesn’t speak much English — that she is proud she is able to provide for her children.

She is working in the underground economy as she waits for her case to be heard in court, which is why she asked that we not use her full name or the names of her children in this story. Even in California, with Medi-Cal and a so-called “sanctuary bill”, it’s hard to make it as a single mother of four children. Yocelyn’s legal case and mental health take a back seat to raising her family.

Yocelyn opens the door to enter her apartment one day in October. Two of her children follow her inside, dragging their feet as if their school backpacks are weighing them down. From the second floor of the unit comes the cry of the toddler with chickenpox. His 13-year-old aunt has been unable to console him for an hour. She has chickenpox too.

Yocelyn runs upstairs and comes back with a shirtless boy in a diaper. His back is covered in blisters and there are a few scabs on his forehead. Luckily, the three other children have already had chickenpox, so she doesn’t have to worry about them getting sick.

Hear Yocelyn, in Spanish, talk to her 5-year-old son. She tells him to take a shower as he tries to persuade her that he has chickenpox like his little brother.

It’s 6:30 p.m. and the end of a 10-hour work day for 29-year-old Yocelyn. She makes a living as a maid at a hotel near Disneyland in Anaheim. Her wavy black hair is pulled back in a bun with a few unruly pieces sticking out.

With the baby still in her arms, she rushes to the refrigerator and pulls out a bag of pork chops. She uses one hand to grab a pan, add some oil, light the stove and throw on the meat. Her son continues to cry. Her 5-year-old comes around and she admonishes him for not going to school that day.

“I couldn’t find my pants,” he says in his defense, looking up at her with big, pleading eyes.

Her children keep her going, but they also remind her of her violent past. Yocelyn was raped in El Salvador by gang members. A few months after she fled, she realized she was pregnant. Her son, her fourth child, just turned 2. That’s the main reason she asked that we not use her children’s real names — she’s not ready for them to know what happened to her. She also fears that gangs will identify her family in El Salvador and she is concerned that immigration authorities could find out that she is working without a permit.

When she’s sad, Yocelyn says, she hides in her room to cry because if she cries in front of her children, they’ll cry too. She doesn’t want her 2-year-old to see her sad.

“It’s not his fault,” she says.

But there are times she looks at him and she can’t help feeling something strange.

The family’s first immigration court date is in April 2018, almost two years after they presented themselves at the border for asylum. A friend recently told her that she should have also filed paperwork to ask for asylum within a year of arriving in the US. Immigration attorneys say this is true, that people seeking asylum need to file an I-589 application.

Yocelyn didn’t know that in 2016 — no one at the border or while she was briefly in immigration detention told her about the form. As a result, she is an asylum seeker but not on paper, and to the government she is an undocumented immigrant to be deported. Despite making many phone calls, she hasn’t been able to find a pro-bono attorney to help her make her asylum claim for her children and herself, before her court date.

“I don’t feel like going to work or getting out of bed. I don’t want anything. I don’t want to play with my kids, I don’t want to go out on the street, I don’t want anything. I think I’m being ridiculous,” Yocelyn says. “I feel like I’ve given up without even putting up a fight. I don’t care anymore if I have an attorney or not.”

Yocelyn doesn’t like to talk about these troubles with the people in her life. She continues to do what she has always done: go to work.

“I don’t want to be pitied.” She continues, breathing like it’s a mantra: “I’m alive. I’m here. I’m fighting and for as long as I can. That’s what I’ll do.”

So it was hard for Yocelyn to explain to border agents at Nogales why she was there. She didn’t want them to pity her either.

Yocelyn was among more than 26,000 mostly Central American adults and children, who arrived together as families at ports in the southwest and were detained by border agents from March through September 2016. Customs and Border Protection calls them “inadmissibles,” people who present themselves to agents at the border but cannot be allowed to freely enter the US. The agency apprehends many more people who don’t cross at ports.

In the 2017 fiscal year, almost 30,000 people in families and more than 7,000 children traveling alone presented themselves and were detained at the southwest border. Over 75,000 people in families and over 40,000 children were caught trying to enter the US between ports, according to government data.

While the total number of people apprehended without travel documents has gone down by more than half in the last decade (PDF), violence in Central America has pushed many people from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala to migrate north.

When Yocelyn presented herself at the border, an officer asked her questions for an hour and half. She remembers the man was kind and said they would help her. She doesn’t recall anyone saying she would have to file paperwork for asylum.

People requesting asylum at the border are turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). They are often sent to detention centers where they wait for an officer of US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to conduct a “credible fear interview.” Some attorneys say that’s not what’s happening for many asylum seekers, though. Some people are being flatly turned away, while others are released by ICE with a date to check in with them or a notice to appear in court.

According to CBP spokesperson Teresa Small, nothing has changed in this process since Yocelyn’s crossing in 2016. They ask questions to complete the “necessary paperwork” and turn people over to ICE. She says her agency does not assess people’s claims with credible fear interviews. That’s up to USCIS, usually at an ICE facility.

A USCIS spokesperson directed questions about this process to their website. When someone is given a credible fear interview, it says, they also get information about the process to seek asylum and a list of places to go for legal help.

Also: 20 years ago, asylum seekers were not automatically put in immigration detention

At the border, the government separated Yocelyn and her children from her brother. He was sent to the Eloy Detention Center in Phoenix, privately operated by Core Civic, while she was sent to an immigration holding facility in Tucson, Arizona, where they spent the night. Yocelyn and the four children were placed in a cell known among immigrants as “la hielera,” the refrigerator, because of how cold it can get. It was so cold, says Yocelyn, that her 5-year-old, then 3, turned purple after an asthma attack in the early morning.

Immigration officers gave Yocelyn her belongings so she could look for his inhaler. At 11 a.m., they released them.

“They didn’t ask me for an address, they didn’t ask me for anything. I guess they said, ‘If he’s going to die he better die out there,’” she says with an uncomfortable chuckle.

Before she left the detention center, she says she was given a piece of paper with instructions to go to an immigration field office 15 days later in Los Angeles. Then she was driven to a shelter for migrant families in Tucson. She spent a week and a half at the shelter until she connected with a relative in California with whom they could stay.

Her brother was in detention for nine months until May 2017. Yocelyn helped him find a private company, Libre by Nexus, to cover his $25,000 bail in exchange for him paying a monthly fee of $420 and wearing an ankle bracelet monitoring device. It’s a common fee for this bail-bond company, which went national in the last few years by focusing on clients in immigration detention.

Yocelyn’s story is not unique either. Gender violence is a reality of life in El Salvador where rape is often used as a weapon by gangs to terrorize. There were 3,947 sexual violent crimes reported to the Salvadoran civil police in 2016, according to an analysis by ORMSA, a Salvadoran feminist organization that advocates for women’s rights. Of those, 47 percent were committed against minors.

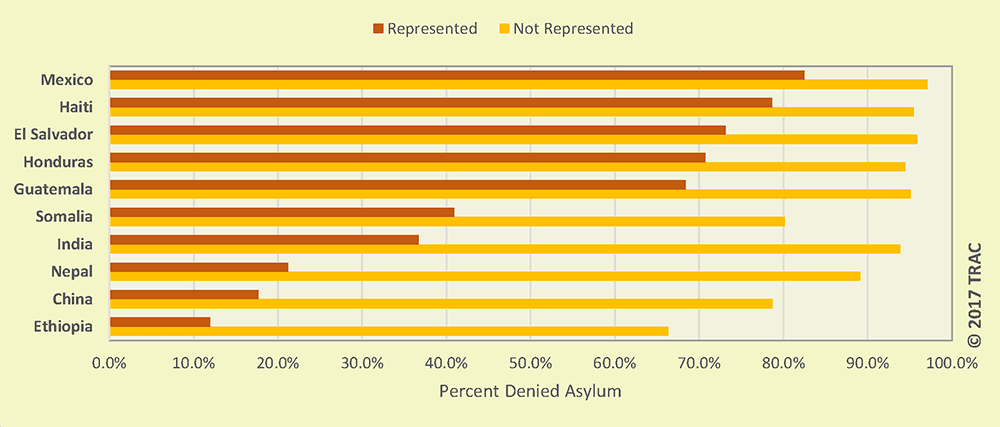

El Salvador was second only to China in the number of asylum cases presented in immigration court in the last six years. There were 15,667 asylum cases from El Salvador, according to an analysis from the TRAC at Syracuse University. Almost 80 percent of applicants were denied asylum.

Some cases of violence and abuse can be horrific, but might not fit the legal definition of warranting asylum, says Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of the Immigrant Defenders Law Center in Los Angeles. That’s why having an immigration attorney to help present the legal arguments is so important, she says. Her organization provides pro-bono lawyers to people in immigration detention.

Having a lawyer is crucial in asylum cases like Yocelyn’s; people with representation are five times more likely to win their cases, according to TRAC’s analysis. Of those from El Salvador who were denied asylum, 96 percent had no lawyer.

Also: A migrant from El Salvador gets her chance in immigration court

But working with a therapist can be essential too, because it can help unearth parts of a person’s history that could be crucial in court, says Toczylowski. Beyond the legal case, therapy can also help families cope with the stress of deportation proceedings and the trauma that followed them to the US.

But for many people in the deportation queue, mental health services are hard to come by. Asylum seekers can get work permits 150 days after they apply and then also qualify for health coverage via the exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act. But without an attorney, Yocelyn didn’t file any paperwork, so she has no work permit or health insurance.

Undocumented immigrants like her are not eligible for federal public assistance. While some states provide limited benefits, they cannot legally get monetary or food assistance or health care from national programs. Refugees, granted status before they arrive, are eligible for benefits, while immigrants with legal permanent residence have to wait at least five years to become eligible.

Even still, a 2013 study by the libertarian Cato Institute found that low-income immigrants who are eligible used public benefits at lower rates than low-income US-born citizens.

Asylum seekers have similar difficulties to refugees, but access to none of the benefits, says Cristina Muñiz, a psychologist who specializes in family therapy and complex trauma at the Center for Child Health and Resiliency in Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx in New York.

“There’s no difference. And yet their experience is very different because they come here and they don’t have access to basic services. They don’t have a safety net,” she says. “As a psychologist, I can say it’s very concerning.”

“It’s extremely challenging for clients to find support because there are only a limited number of free or low-cost mental health service providers,” says Karlyn Kurichety, an attorney who works with asylum seekers for the nonprofit Central American Resource Center.

Asylum seekers can suffer from depression, PTSD, complex trauma and anxiety. If they suffered violence, they might have difficulty trusting others or be susceptible to substance abuse. They also can experience further trauma beyond whatever caused them to leave their countries, says Deana Gullo, a licensed clinical social worker in Santa Ana, about 10 miles from Anaheim.

The experience is known as the “triple trauma paradigm,” she says. A person leaves their home country after several traumatic experiences, then experiences more violence during their journey. When they reach their destination, they face the challenges of life in a new country on top of the complicated maze of immigration proceedings.

“The level of complexity of that is overwhelming,” says Gullo. She is often contracted by attorneys to present mental health evaluations in immigration court.

On a Saturday in October, Yocelyn hops on a public bus at around 8 a.m. She pays in two $1 bills and rides for 45 minutes past shopping centers, restaurants and grocery stores until she reaches a block of hotels. She’s only been working here for 15 days. Her last job was cleaning houses — her boss was another immigrant. She was from Mexico so they could communicate well in Spanish, but she had a strong temper. Once, Yocelyn’s first boss hit her on the back of the head.

Yocelyn quit cleaning houses. Another mother at her children’s school told her about an agency that subcontracts with hotels.

The agency pays her $10.75 per hour, $1,500 to $1,800 per month after taxes and social security are deducted from her checks. She is not sure how much the agency makes. She doesn’t have a bank account, so she pays $8 for every $100 to cash her paychecks with a store owner who does the transaction under the table.

“This country is very expensive. Everything goes to your rent,” Yocelyn says. “For one person alone, it might be easy. But for a mom with four kids, it’s tough. They demand. It doesn’t matter if you have or don’t have. They want to eat and go to Yogurtland.”

Yocelyn pays $1,000 in rent, including gas and electricity for the two-bedroom apartment. Her brother pays $700 more and her boyfriend, Mario, makes up the rest of the $2,500 monthly cost. Three of her children share one of the bedrooms in the apartment with her brother and her 13-year-old sister. Yocelyn and Mario have a room of their own where she keeps a crib for her youngest son.

She also sends $150 every month to her mother back in El Salvador.

“En este país no se puede perder el tiempo,” says Yocelyn. You can’t waste time in this country.

Immigrants like Yocelyn pay taxes that are taken out of their paychecks, both to the federal government and states. In California, 3 million undocumented immigrants pay $3.1 billion in income and sales tax, according to an analysis released in 2017 by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. The non-profit and non-partisan research organization estimates undocumented immigrants pay $11.74 billion a year in taxes, nationwide.

It’s 15 minutes before 9 a.m., her clock-in time, when Yocelyn gets off the bus. She worries when the crosswalk light takes too long to change. When she gets to the hotel, she enters through a side service door.

Inside the hotel, families with children wearing Mickey Mouse T-shirts and ears are finishing breakfast. One blond-haired boy draws a pirate’s sword to go with his khaki-colored pirate’s coat. A girl holds a stuffed brown horse under her arm.

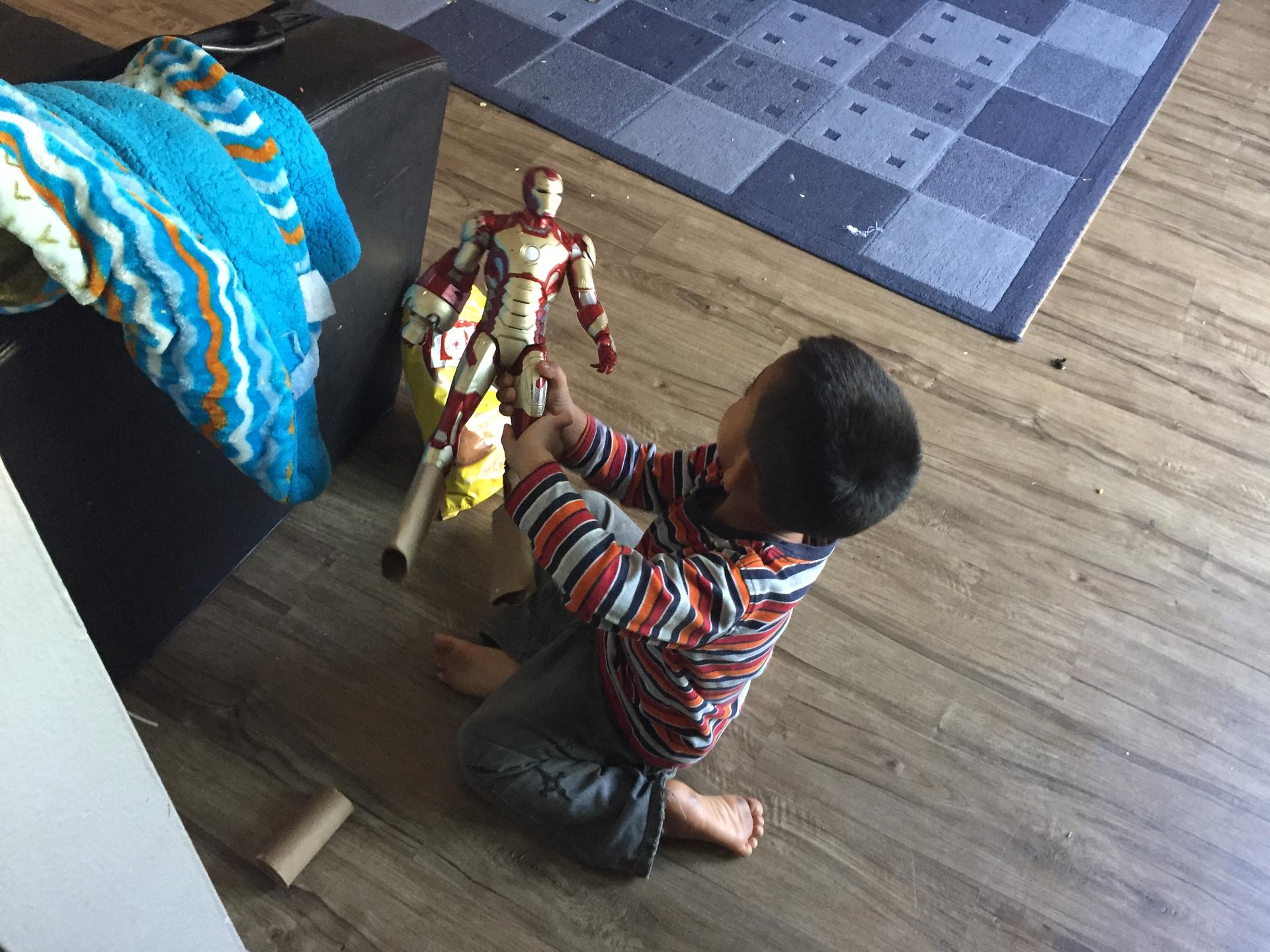

Yocelyn left her own children that morning with a warning not to fight. They were glued to the TV watching “Super Libro,” a series of cartoons in Spanish that feature stories from the Bible. This episode: David and Goliath.

The kids will spend all day at home with their aunt and uncle, who hasn’t gotten out of bed in three days because of the chickenpox. Despite the illness, this is her children’s first stable home in three years and that makes Yocelyn proud. Sometimes she feels guilty too for what they had to go through to get here.

At the end of a long day, Yocelyn reclines on a black leather sofa with her boyfriend to watch a telenovela, “Sin senos sí hay paraíso.” It’s a show about two sisters who make difficult decisions in order to survive poverty and mafia violence in Colombia. Yocelyn and Mario say they like it because of the good looking women and men on the show.

She met Mario at a Laundromat about eight months ago. He helped her find the apartment where they live now. It is the nicest place she’s ever lived. In addition to the bedrooms, it has two bathrooms, a patio and a kitchen with a microwave and dishwasher, part of an apartment complex that has a shared swimming pool, a hot tub and gym.

And her children are being educated. A 1982 Supreme Court ruling, Plyler v. Doe, declared that states cannot deny undocumented children a public education.

But it’s not easy for Yocelyn to navigate the American education system. In November 2017, the principal sent a police officer to her house because her two boys missed class. She had called the school that morning to say she was taking them to get vaccines.

“How scary to see an officer at the door,” says Yocelyn. He didn’t ask her for identification and went on his way once he saw the children were there and OK. But Yocelyn still worries. “The principal thinks I mistreat my children.”

On a day that Yocelyn is running late from work, Mario picks up the three older kids from school, while her toddler is at home with his aunt. Mario plays ranchera music on their way back home. But when the radio plays “Bohemian Rhapsody,” it’s even better. Mario is 51, and a big fun of Queen.

Yocelyn’s 5-year-old calls him papi and likes to say he too is from Guerrero, the state in Mexico were Mario comes from.

“How did it go in school today?” Mario asks from the driver’s seat.

“Good. I didn’t hit any other kid,” replies the 5-year-old, from the back.

Mario laughs at the answer.

“Mario es de los hombres que ya no hay.” There are no men left like Mario, Yocelyn says. She asked that Mario too only be identified by his first name; it would be too easy to identify her family with his full name.

Yocelyn doesn’t feel as lonely now that she has Mario in her life. At times, though, she worries he will get tired of her fear and distrust.

“I’m very afraid. I can’t live well. Mario says I’m antisocial,” she says. “I don’t make friends, even if I want to. I don’t feel well, I’m afraid of people.”

She’s afraid of Mario, too. He hasn’t given her reasons to worry. Still she can’t help it.

“I tell him not to even think of harming my children,” she says. “I tell my daughter, ‘If he touches you, tell me. I’ll choose you over anything.’ I feel like at any moment this is going to bother him, that I’m repeating this over and over.”

Yocelyn grew up in a small town with a religious family. When she was 10, her father, a pastor in a Christian church, started sexually molesting her.

“I thought it was normal, that it happened in all homes, because it happened every day,” she says. At first she blamed it on herself. Her mother wouldn’t defend her when her dad turned violent. He was violent with her mother, too.

Yocelyn stopped eating and started using drugs.

She consumed whatever she could get her hands on. At first she would breathe what’s known in Latin America as tíner, paint thinner, and also cement glue. Later, she used crack, which she could buy for $1 a dose on the street.

She left her home when she was 11 and then got caught in a house where drugs were being sold. She was taken to a juvenile institution that she says felt like a jail.

By 18, she was pregnant with her daughter, her first child.

She once heard a phrase in the animated film “Sing” that stuck with her: “The good thing about hitting rock bottom is that the only thing you can do is go up,” she remembers. It was said by Buster Moon, an optimistic koala in a blue suit and red bow tie.

This life she has now feels like it is going up at times. But making a life in the US was never her goal.

Yocelyn once built a house in Cuscatlán, El Salvador, with money she earned selling plastic food containers. To buy a parcel of land, she lived for a year on an empty lot with her three children and her then partner, the father of her two younger boys.

She calls the lot a basurero because neighbours used it to dump trash. Her temporary home sat on a slope and didn’t have a floor. The walls were made of plastic, often trash bags. When it rained, the water ran underneath her children’s beds.

But she saved enough to pay $150 per month until she bought the $5,000 parcel. Then she spent about $1,000 to build the house. She used bajareque, a type of thin bamboo, mud and cement.

“Estaba bonita mi casita, era mi casita,” she says. “It was a pretty home. It was my home.”

It wasn’t one single incident that led her to leave El Salvador.

In 2014, her partner of more than eight years started drinking and putting her and her older boy down. When she stood up for her son, he hit her on the head. She reported the incident to local authorities, but didn’t want to file charges. Instead she told him to leave.

Three months after they split up, he got in trouble with a gang for being involved in the murder of one of their members. They came looking for him.

One early morning, she was on her way to her mother’s small restaurant with her kids, who were dressed for school, when a young man on a bicycle pulled a gun and demanded that she tell them where her former partner was. She knew the answer but didn’t want to say because it would endanger other innocent members of his family.

“If they went looking for him where he was, they were going to kill from the youngest to the oldest, because that’s the way they are. In a bakery, they killed even the dog — what could the dog do to them? A 6-year-old? An 8-year-old?” she says.

A group of women walked by in a morning procession for the Virgin Mary and the man on the bicycle hid the gun. She grabbed the kids and ran straight to her mom’s restaurant to decide what to do.

Her daughter was 7 when it happened.

“I don’t like when she starts remembering, because it makes her cry,” Yocelyn says.

She went to a human rights organization that connected her with a nonprofit in Guatemala where she could stay safely with her children. More than a year went by and she wasn’t able to work outside the shelter to improve her children’s lives. Also, her ex-partner found them and asked to be given shelter too. While the men and women lived separately, she wanted to be farther away from him.

So when her mother told her that the man who threatened her no longer lived in their community, she was eager to return to El Salvador with her children.

“I wanted to give my children a better place,” she says. She realizes now how naïve it was to think her problems would end with that one man. “I feel people will judge me because I made mistakes.”

When she got back to Cuscatlán in May 2015, there was nothing left in the home she had built.

Eight days after she arrived, she was captured by gang members on her way out of her mother’s home.

They took her to an abandoned house where neighbors had, on several occasions, discovered the bodies of murdered women.

“I was sure they were going to kill me,” Yocelyn says.

The men started hitting her with a broom on her back and legs, until the handle broke.

“They raped me repeated times,” she says. “They hit me. But I never imagined I would get pregnant. At that moment … the truth is I never thought I’d leave that place.”

She was naked and bleeding on the floor.

Among the group was a young man she knew from the neighborhood. They had grown up together on the streets. He dragged her by the hair and kicked her out of the house. He told them to let her go, but that if she came back he would kill her.

“I’m afraid when I think of this, even though I’m so far,” she says. “My feet tremble when I remember.”

That night, Yocelyn slept in a park. She was in pain and throwing up blood. She didn’t go to the hospital because she thought the doctors would call the police, and the police would force her to say who hurt her.

The next day she went to Ciudad Mujer, a Salvadoran government program which focuses on supporting women. She was bruised and still bleeding. The officials there asked her to identify the culprits, but she knew the gang would come back to harm her family if she did. She realized she would have to return to Guatemala. This time alone.

“At that moment, I felt like I’d rather be dead.”

Yocelyn didn’t see her children for 14 months. They stayed with her mother.

“It was very tough because I’ve never been away from my children. The youngest one — I was still breastfeeding him,” she says. He was a mama’s boy, she says, always clinging to her legs.

She stayed in a room she rented because she didn’t feel it was safe to return to the shelter. It was there that she realized she was pregnant. It was too expensive to see a doctor to confirm it, but she knew. She left for Mexico City where she thought she might find work.

Abortion is legal in Mexico City, and she considered it, but she was too far along in the pregnancy. She stayed in a Catholic shelter run by nuns; they offered the possibility of giving the baby up for adoption.

There were times she prayed to God that she would fall asleep and not wake up. She would punch her stomach when her baby kicked so he wouldn’t move.

“I made him suffer,” she says. “It pains me.”

He was born in February 2016. She didn’t want to see him until doctors convinced her to breastfeed. After that, she couldn’t give him away.

“I cried every time I saw him. I cried and cried and cried for five months.”

Maternal instincts kick in for some women who become pregnant as a result of rape and decide to have the child, says Gullo, the clinical social worker.

“A lot of them just tend to sacrifice their own self or their own feelings for the good of their child,” she says.

Four months later, Yocelyn got a call that there were strange people surrounding her mother’s home. Her mother worried gang members were trying to harm the children. Yocelyn decided to go back for them. She left her baby in the care of an attorney connected to a Catholic shelter in Chiapas, Mexico, near the border with Guatemala, and took off for El Salvador.

She spent less than 10 minutes in her mother’s house before she and the three children left with just a change of clothes. Three days later, the whole family was back together in a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico.

The youngest boy, whom she left when she want to El Salvador the second time, didn’t even remember her.

Someone saw Yocelyn when she was in El Salvador and threatened her brother to try to get him to reveal where she was. He fled too, and joined them in Mexico.

“I’m not going to the United States because I want to,” she says. “People don’t understand. They think we are going there because we want to work and get paid in dollars.”

Now, in Orange County, Yocelyn feels stress thinking about her upcoming court case and not having an attorney. Sometimes she also forgets things, like the code to clock in at work or her mother’s last name. That makes her feel strange, but she cannot stop to consider her mental health.

“I arrive home to cook, I don’t have time left. The day I take a break, it’s to organize things, give [the children] a good bath because they don’t do it well,” she says. “I don’t have time left to say, ‘I’ll go to a psychologist.’”

Hear Yocelyn speak in Spanish about her fears of being deported to El Salvador.

It is a loop that feeds into itself.

Families seeking asylum or facing deportation proceedings feel stress trying to find legal services, jobs, childcare or even buying food to eat every day, says Elena Fernández, the behavioral health director for St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.

“They go into depression, they don’t want to leave their home,” she says.

Which is a problem in Orange County. In California, children under 19 can be covered by Medi-Cal, the state Medicaid program, regardless of their immigration status, but adults are not. A Los Angeles County program called “My Health LA” gives residents who cannot get health insurance free access to primary care. And St. John’s provides psychological evaluations and mental health services to about 2,200 undocumented immigrants every year, regardless of their ability to pay. The Los Angeles programs struggle to meet the great need of their patients, and Orange County, 40 miles south, has even fewer options for low-income, undocumented people.

“The health centers are struggling to meet the demand,” says Isabel Becerra, CEO of the Coalition of Orange County Community Health Centers, which runs clinics that provide mental health services with sliding scale fees, regardless of the immigration status of a patient. “There’s not enough bilingual, bicultural providers to adequately address the mental health needs of our populations.” So, at times, she says, patients can wait weeks to be referred to a therapist.

There’s a clinic not far from where Yocelyn lives where she could pay based on what she can afford. But after living in the neighborhood for more than 10 months, she still had never heard of it.

“It’s a cultural barrier. It’s a physical barrier. It’s a transportation barrier,” says Rogelio Valdez, an immigrant advocate and former case manager at AMANECER, a nonprofit that provides behavioral health services to Latinos in Los Angeles County and nearby areas.

Six to eight months of sessions could cost $3,000 to $4,000 without insurance, says Timothy Ryder, executive director of AMANECER. AMANECER doesn’t ask about immigration status either, but Ryder estimates that it serves 500 to 600 people people per year who are undocumented.

Seeking mental health services can be taboo among some Latinos, who fear people will judge them as “crazy,” according to mental health advocates. But some immigrants also fear that getting help will affect their immigration cases.

Lillian Zazueta, an advocate at St. John’s, says it’s a typical question she gets from immigrant parents: “Would this put me in danger of being reported to immigration?”

She tries to assure them that receiving therapy won’t affect them.

That the Trump administration is considering directing the Department of Homeland Security to penalize the legal residency applications of those who use publicly funded services does not help ease the barriers to getting mental health care.

On Sunday, while Yocelyn is at work and her brother is at home with the kids, her 10-year-old daughter draws a map of their apartment and numbers each room. Then the three older children draw numbers to choose which rooms they will have to clean. One of them gets the patio and pouts. Each task comes with pretend money, a symbolic reward for their work.

When they go downstairs, the toddler is hungry so his sister gets him some cut mango from the refrigerator, knocking tomato sauce on the floor in the process. They all rush over to inspect the mess.

Yocelyn comes back from work 10 hours after she left home, and the four children compete for her attention. She pulls a few coins out of her pocket: “My sad tip from today.” She puts the money back in her pocket. Then she takes off her black tennis shoes and sits on the leather sofa.

“I’m going to dress like a Power Ranger when the end of the world comes,” says the 5-year-old.

“And when is that?” Yocelyn asks.

“Next month,” he says.

Her toddler just wants to be in her arms. Yocelyn holds him and sings a lullaby.

“They are the engine that moves me to get up every day,” she says. “I dream of many things, even becoming a grandma.”

Valeria Fernández is a fellow of the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative, part of the International Women’s Media Foundation. The foundation provided some support for this story.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?