Federal investigators walk into the World Trade Center garage on March 2, 1993, to investigate an attack that killed six people. The bombing set off fears of foreigners and asylum seekers in particular.

On February 26, 1993, a group of Islamic extremists parked a rental van with a 1,300-pound homemade bomb in its trunk underneath the World Trade Center in New York City. The subsequent explosion killed six people, injured more than 1,000 and was the largest terrorist attack on US soil at the time.

As Americans processed the news, confusion turned to fear. The attackers were followers of radical sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman, who was living in the US despite being on a terrorism watch list for his alleged role in the 1981 assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. His green card was revoked in 1992, but he requested political asylum and was awaiting his hearing

An influential 60 Minutes episode ran several weeks later. It was called: “How Did He Get Here? Asking For Political Asylum Gains Easy Entrance to US.” The segment opened with a conversation between host Lesley Stahl and Dan Stein from the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

“Every single person on the planet Earth, if he gets into this country, can stay indefinitely by saying two magic words: political asylum,” Stein said. “You say 'political asylum,' you get a work card and you get an indefinite right to stay until the immigration service gets around to hearing your claim.”

The segment goes on to describe the lack of scrutiny that asylum seekers were given at that time and the benefits afforded to them, including a work permit, while they awaited court proceedings — which could take years.

“This was before the Internet and most people watched 60 Minutes,” says Michele Pistone, director of the Clinic for Asylum, Refugee and Emigrant Services at Villanova University in Philadelphia.

That report, she says, set the stage for bipartisan support of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, known by the hard-to-remember acronym IIRIRA. Among other changes, the law made it standard practice to detain asylum seekers while their cases are processed.

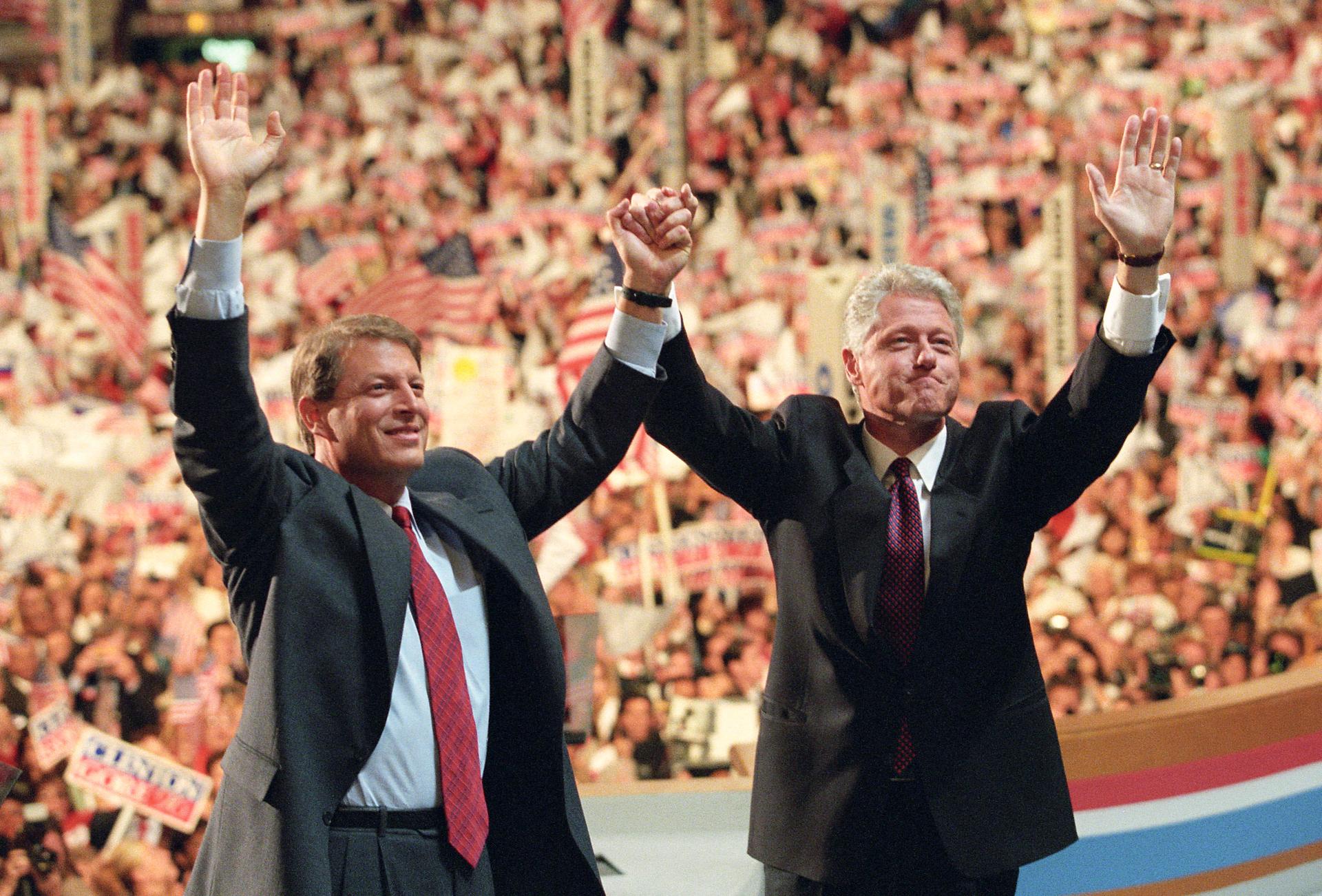

The premise of IIRIRA, enacted during the Bill Clinton administration, was to stop dangerous foreigners like Abdel-Rahman from migrating to the US. The result, though, was a boom in immigrant detention.

“The ‘96 law impacts all of my work,” says Robyn Barnard, an attorney at Human Rights First. Her clients, who she either represents herself or connects with pro-bono attorneys, are often asylum seekers in detention.

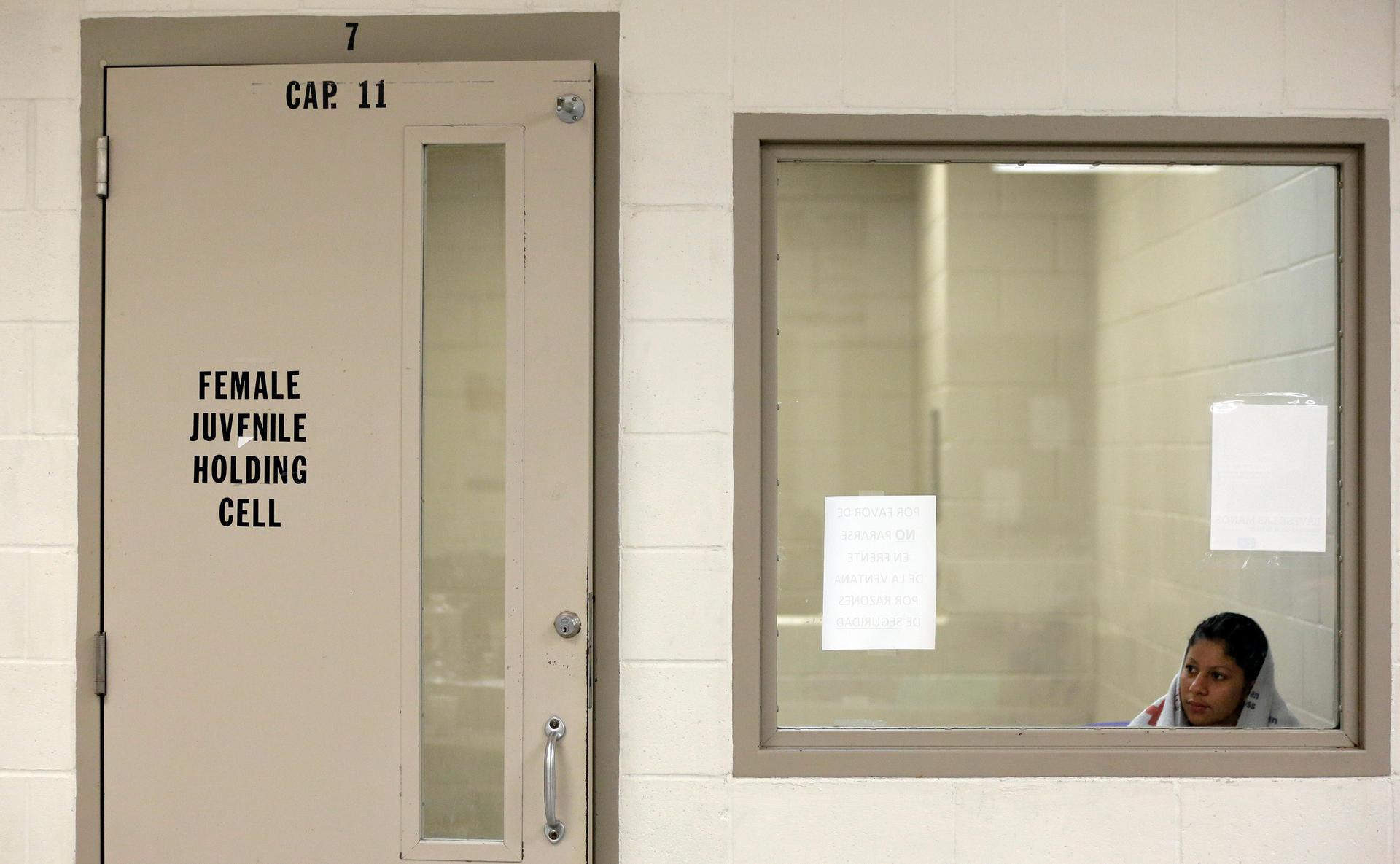

In 2014, more than 44,000 asylum seekers were held in immigration detention. That’s 77 percent of all asylum seekers in court proceedings, according to a Human Rights First report published this August (PDF). But just two decades ago, Barnard’s work would have been mostly unnecessary in America.

Advocacy groups say that in 1996, there were slightly more than 6,000 beds available for immigrant detainees. Now, the government fills about 34,000 beds per day.

It’s not just that there are more asylum seekers entering the country, though. In 1996 more than 116,000 “affirmative asylum applications” were filed — that is, people who came forward to request asylum (PDF). Last year, 83,000 applications were filed (PDF).

This law was intended to increase national security, and to weed out people who were claiming persecution but actually coming to the US for financial gain. This type of economic migrant was seen in the boats of Chinese peasants arriving on US shores in the early ‘90s. They had been promised jobs by the smugglers who brought them — the scheme came to national attention when one boat crashed in June 1993, killing at least seven people.

What they got when they arrived amounted to indentured servitude. Some critics said lax asylum laws provided incentive for economic migrants to come en masse.

“The best way is to actually hold the people in detention, and word will get back,” Richard Kinney told the Washington Post in 1993. He was the spokesman for the Immigration and Naturalization Service, a now-defunct federal agency.

Increasing immigration detention was what the law was intended to do, says Ruth Wasem, a professor of public policy at the University of Texas, Austin. Wasem was an immigration specialist for the Congressional Research Service when the law was written and passed.

“There often is this view: one person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist. If you have asylum seekers coming from war-torn areas where it's hard to tell the good guys from the bad guys, there are people who view asylum seekers more suspiciously than they would other immigrants,” she says.

IIRIRA made it mandatory that anyone who arrives at a border or an airport and declares that he or she is seeking asylum is detained. If immigration officials find their claim not credible, they are put into a fast track for deportation, known as “expedited removal,” before ever having a day in court. If their fear is determined to be credible, then they are released only if officials decide that they are not a flight risk and they can afford to pay a bail bond to the court — which they often cannot.

Today, women and children fleeing from targeted gang violence in Central America’s Northern Triangle — Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras — are frequently subjected to IIRIRA. In 2014, the Obama administration announced its plan to deal with the influx of families from this region arriving at the US-Mexico border: step up detention and fast-tracked deportation. At the time there were 100 beds in immigration detention for parents with children. There are now 3,700 (PDF).

Often, by the time Barnard meets a client, he or she has been in detention for months. The hardest part of her job, she says, is telling asylum seekers that she and her nonprofit organization simply don’t have the bandwidth to take on their cases.

“It's really sad to have to respond and say, ‘Here are some documents you could use in your case,’” she says, thinking of the numerous detained asylum seekers who have to navigate the complex immigration system on their own, from behind bars.

Typically, the Human Rights First report found, asylum seekers linger in detention for months and sometimes over a year. On average, Barnard says, her clients are detained six to eight months. The US Supreme Court is currently deliberating on a case that will decide whether immigrants detained over six months should be automatically eligible for a bond hearing.

“Many of our clients come to the US specifically to seek protection, so they believe that they should do the right thing and tell the authorities as soon as they have any interaction with them that they're here to seek asylum,” she says. However, she says, her clients are surprised when they are put behind bars, with no guarantee of a day in court.

“They are wholly reliant on Immigration and Customs Enforcement to decide to release them from detention,” she says.

She recalls one client who was recently granted refugee status. He is gay and fled persecution for his sexual orientation in his home country, El Salvador. During his nearly one year in detention, she says, he was sexually assaulted.

Another recent client, a woman from Colombia, fled her abusive husband, fearing for her life. She spent eight months in detention — despite letters from her family in the US begging she be released — before being granted refugee status.

Wasem says mandatory detention and expedited removal were designed to help genuine asylum seekers by weeding out those who, as lawmakers described, were trying to “game the system.”

“Most would agree that when you have a system that is overwhelmed and backed up with frivolous claims that the bonified asylum seeker is also disadvantaged because they're stuck in this backlog, in purgatory of immigration status,” she says.

“The idea was that it would deter the abuse of the asylum system,” says Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies at the conservative Center for Immigration Studies which advocates for tighter restrictions on immigration. “If there were dangerous people who were asking for asylum, they would not disappear into the woodwork. The immigration agency still had the discretion to release people if they felt that they could do so safely,” she says.

In the 20 years since IIRIRA, Pistone, at the Villanova University law clinic, has advocated for reform. In particular, she hopes that expedited removal and mandatory detention only be used in emergency situations, not as blanket tools.

There has not been meaningful changes to the law, nor has public perception of asylum seekers drastically changed, but Pistone says she is hopeful. At the law school where she teaches, colleagues have begun to express interest in auditing her classes and learning how to advocate for refugees.

Even with President-elect Donald Trump’s tough rhetoric on asylum seekers, Pistone thinks more and more Americans are beginning to recognize the inadequacies of our asylum system.

“At a grassroots level, I'm seeing more support than ever,” she says. Her peers, she says, increasingly want to learn to volunteer as asylum attorneys.

More: Many women seeking asylum in the US have been released from detention — but with ankle monitors

First person: What it’s like to represent detained immigrants in overloaded courts — day in and day out

Also: Idaho’s first Syrian refugee wants Americans to understand their country's vetting process