After the California wildfires, community leaders are trying to rebuild homes — and trust in government agencies

At a Spanish-language town hall on Oct. 21, immigration lawyer Richard Coshnear urges all undocumented residents affected by the fires to speak with an immigration lawyer before filling out their application for aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. "Right now we think that the information that a person gives to FEMA is not secure or confidential," said Chosnear in Spanish.

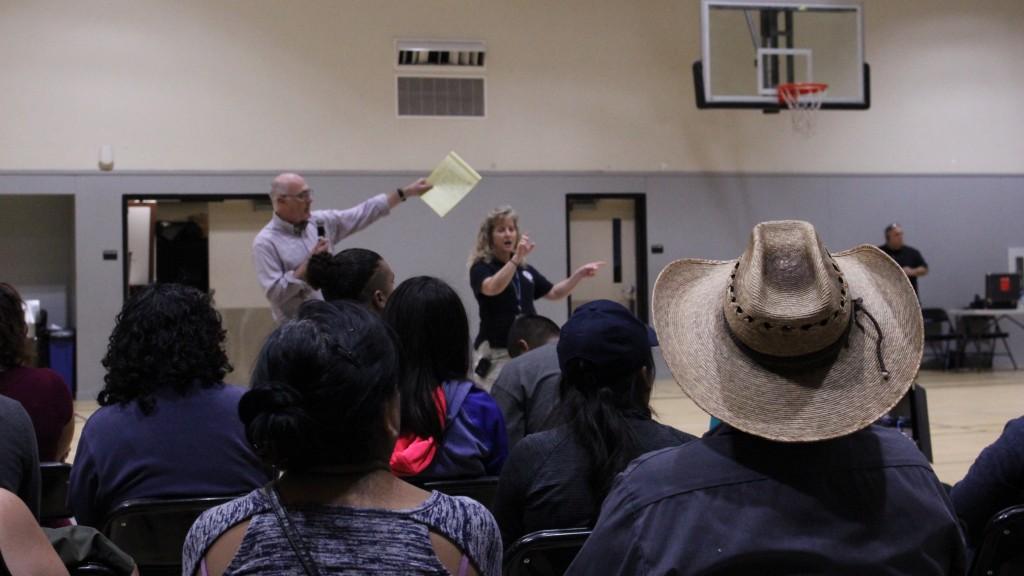

On Oct. 21, when wildfires in Northern California were still smoldering, about 150 people gathered at a middle school gymnasium. Thousands more watched the livestream on Facebook. Officials in Sonoma County, the region most devastated by the fires, had put together a Spanish-language community forum to address the concerns of the Latino community — the first of its kind in the county.

When the floor opened for questions, silence filled the air. But soon, hands started flying.

A man stood to ask if the Federal Emergency Management Agency could provide any guarantee to undocumented parents who applied for aid on behalf of their citizen children that their information would not be shared with immigration agents.

The question was one that lingered in the minds of families who had lost homes, employment or both in the fires. The answer, however, did not provide any certainty.

David Passey, a FEMA director of external affairs, insisted that from other disaster zones in Florida and Texas, he knows of no cases where information was shared with immigration officials.

"It's not a guarantee, but we are interested in helping you to the extent that we can," Passey said in Spanish at the meeting.

That meeting is just one indicator that, for the region’s immigrant residents, uncertainty remains even though the wildfires were put out more than a month ago. And for community leaders, especially those assisting non-English speakers and undocumented residents, the work has just begun.

In the wake of the most destructive wildfires in California’s history, officials and community leaders are rethinking how they respond to emergencies. In Sonoma, local leaders said the county struggled to provide safety and support for some of its most vulnerable groups: undocumented immigrants, their family members and other non-English speakers. Meanwhile, fear of immigration enforcement kept many from seeking aid.

As the county looks to rebuild, officials said they hope to address those fears and learn how to better communicate with all residents during emergency situations. Officials said this is especially crucial in a county where Latinos and other immigrant groups make up over a quarter of the county’s 500,000 residents, powering Sonoma’s tourism and wine industry through work in fields, hotels, restaurants, wineries and high-end homes.

“Our economy would fail if we don’t make sure that we’re finding ways to keep people here, if immigrants don’t have access to important resources that even people with more resources need right now,” said Alegría De La Cruz, the county’s chief deputy counsel.

Estimates of the number of undocumented people living in Sonoma County vary, from 28,000 to 38,500. But community leaders said that number does not provide the whole picture. They said the county didn’t anticipate how many citizens with legal status would fear contacting officials because they have undocumented family members.

De La Cruz estimated that about 120,000 citizens, or about 24 percent of the county’s population, belong to so-called mixed status families.

The wildfires, which broke out in the late evening hours of Oct. 8, burned more than 200,000 acres of land, searing through vineyards, hospitals, hotels, schools and homes. In Sonoma County alone, 5,100 residences were destroyed.

The blaze also exposed the isolation many immigrants have long felt in the region — in part due to a highly stratified economy, educational attainment disparities and a severe affordable housing crisis. In the past year, President Donald Trump’s hardline immigration policies have only escalated fear of government agencies within the immigrant community.

Many undocumented evacuees reportedly fled to the coast to camp on beaches or sleep in cars rather than in shelters where they feared government agents would round them up.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) said the agency would suspend enforcement operations “at evacuation sites, or assistance centers such as shelters or food banks,” but the county struggled to convince evacuees this was true.

In the midst of the wildfires, a feud broke out between ICE and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s office. Thomas Homan, then the acting director of ICE, who has since been nominated to take over the position permanently, called the county an “uncooperative jurisdiction” and implied that an undocumented immigrant could have kindled the deadly wildfires. Sonoma County Sheriff Rob Giordano denounced the statement as “inaccurate” and “inflammatory.” The fire Homan referred to in his statement was actually unrelated to the wildfires that devastated the region. The cause of those wildfires is still under investigation.

During the fires, county officials struggled to send evacuation alerts and disaster information in Spanish. Several Spanish-language outlets, including KBBF, a bilingual community radio station, filled the gap.

“If no information is provided, that gives the opportunity for misinformation,” said Bernice Espinoza, a deputy public defender and criminal immigration specialist.

Espinoza informally stepped into the role of language coordinator when she realized no such position existed in the county’s emergency response plan. She spoke to Spanish-language media, translated documents and interpreted at press conferences, while coordinating bilingual staff and volunteers at the county’s Local Assistance Center.

But Spanish is not the only secondary language that’s important in the area. Espinoza said there are sizable Eritrean, Fijian, Cambodian and Laotian communities that might not have received critical information in their native languages. The county is also home to immigrants from southern Mexico who speak indigenous languages like Mixteco, Triqui and Chatino

From the moment the fires broke out, Sonoma County residents mobilized to provide informal alerts, aid and shelter to those who feared government-run programs.

At Windsor High School, hundreds of large boxes of donated food, clothes and toys were dropped off at a grassroots evacuation shelter run by mostly Latino high school and college students.

As impacted residents began applying for FEMA aid, people took notice of a clause on registration forms, which states that personal information “may be subject to sharing” with other government agencies. While undocumented adults are not eligible themselves for FEMA aid, they can apply on behalf of documented members of the household, like US-born children.

Espinoza says a young woman emailed her with questions. Her undocumented mother had filled out a FEMA application on behalf of her two disabled, special-needs sons who are legal citizens, after she lost her home in the fire. The woman worried that her mother’s name might be shared with ICE. “Is my mom going to get deported?” she asked, adding that she would be unable to take responsibility for her brothers should she lose the special legal status afforded to her through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which the Trump administration started phasing out in September.

“I said to her … we’re not gonna let that happen,” Espinoza recounted. “If we need to protect our community with impact civil rights litigation, then we will.”

Three local nonprofits launched a crowdfunding effort called UndocuFund to provide ongoing aid to undocumented individuals who are ineligible or afraid to apply to FEMA. As of Nov. 29, they have raised $2.4 million of their $5 million goal and more than 1,000 families have applied for aid. The number of families could double, according to Susan Shaw, co-director of the North Bay Organizing Project, which helped launch the fund.

The county has not yet conducted a formal evaluation of its emergency response, but county affairs analyst Hannah Euser said officials plan to look at “outreach efforts to ensure adequate response to all community member needs.”

Some local leaders see these fires as a critical opportunity to establish better dialogue and trust between local government and the immigrant community.

One such initiative is “Sonoma County Rises / Sonoma County Se Levanta,” a collective of nonprofit and elected officials that has created a website to solicit feedback from those affected by the fires. The goal is to rebuild a more inclusive and equitable community.

Sonoma County Supervisor Lynda Hopkins, who is on the collective’s board, envisions a series of town halls in local communities, because “all of those decisions being made and all of those initiatives should ultimately be guided by community voice and community representation.”

De La Cruz and Espinoza hope to see more Spanish speakers at future town halls.

“I think Sonoma county's in a great place to understand that language access is the difference between life or death in these kind of situations,” De La Cruz said.

Editor’s note: When this story was published, it contained a photo of an indigenous community worker and his family members. Though the family gave permission for their photo to be taken and published, after it was published they became concerned for their own safety. Though we generally do not alter published content unless it is inaccurate, we will consider requests when it is to protect the safety of individuals in our stories. Accordingly, we have removed the photo from our story.

This story is part of a partnership with students at the Stanford Journalism Program.