Humanity has entered a global warming minefield, climate scientists say

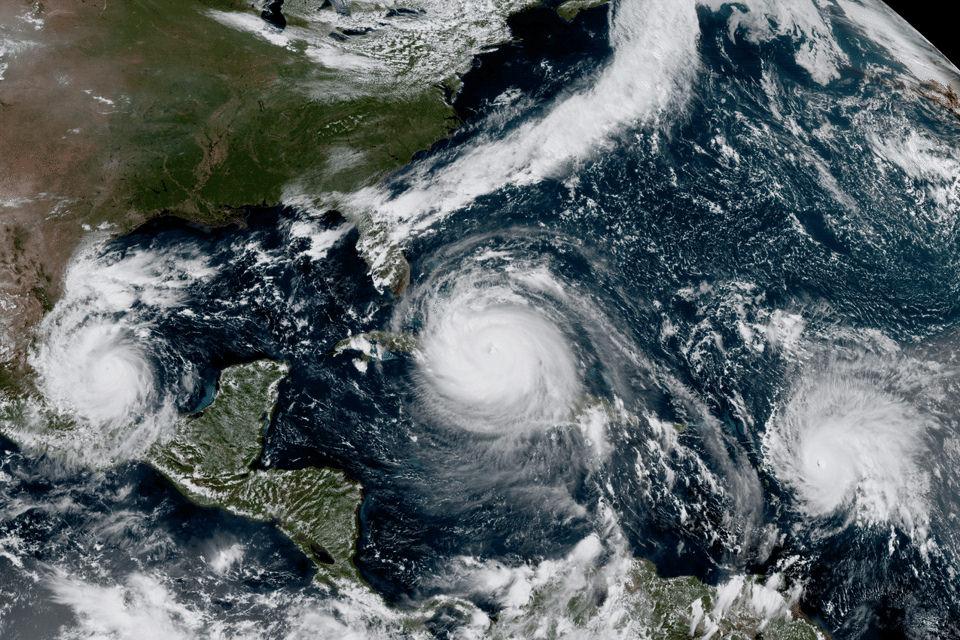

Three hurricanes at once — Irma, Katia and Jose — seen from satellite in early September.

This year’s deadly hurricanes, record-shattering firestorms and severe drought are linked to global warming, and the prospect of more unpleasant surprises seems likely, climate experts warn.

“What we're seeing is the veritable tip of the iceberg,” says Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science and director of the Earth Systems Science Center at Penn State University.

“If we continue on the path that we're on,” he says, “there's no reason not to expect that we will see even more intense hurricanes and more extreme weather events of the sort we're already starting to see — unprecedented flooding events [and] unprecedented heat waves, droughts and wildfire."

Related: Tropical forests are becoming net carbon producers, instead of carbon sinks

Just in the last few years, Mann points out, researchers have measured record global ocean temperatures, which have led to the strongest hurricane in the Northern Hemisphere, Hurricane Patricia; the strongest hurricane in the Southern Hemisphere, Hurricane Winston; and the strongest storm ever recorded in the open Atlantic, Hurricane Irma.

“It’s not a coincidence,” Mann says. “As these ocean temperatures continue to warm, we are going to see the strongest storms get stronger.”

Mann takes issue with the widespread notion that “there's some tipping point — that once we warm the planet enough, once we put enough carbon into the atmosphere, we sort of go off this metaphorical cliff.”

“It's more like we're stepping out onto a minefield and we don't know exactly where those mines are.”

“In reality,” he says, “it's much more subtle than that. There isn't one tipping point. There isn't one cliff that we go off. It's more like we're stepping out onto a minefield and we don't know exactly where those mines are, but the farther we step out into the minefield — the more we warm the planet — the more likely it is that we do set off these mines, that we do encounter devastating tipping point-like changes in the climate.”

The melting ice sheets in the West Antarctic and Greenland are good examples of “mines” that could lead to other catastrophic consequences.

Billions and billions of gallons of freshwater flowing into the North Atlantic could potentially shut down the ocean circulation pattern called “the great conveyor belt,” Mann explains. That, in turn, could devastate fish populations in the North Atlantic, one of the most productive marine environments in the world. In addition, emerging evidence suggests that if that “conveyor belt” were to shut down, waters in the tropical Atlantic and in the Caribbean could warm even more, further intensifying future hurricanes.

Related: This 18-year-old from New York is suing the Trump administration over climate change

For some perspective of where we currently are in the minefield, Mann notes that atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide have increased from pre-industrial levels of about 280 parts per million to just over 410 parts per million — a level that is “unprecedented over millions of years.”

“If that number crosses 450 parts per million, we most likely commit to catastrophic warming of more than 2 degrees Celsius," he says. "Once we warm the planet more than 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit, relative to the pre-industrial, that's when we start to run into the most dangerous mines."

To be clear, he adds, for people in places like the Caribbean Islands, Bangladesh and low-lying Pacific islands, or for farmers in California, “dangerous climate change has already arrived.” Two degrees Celsius is more or less a political consensus about what is achievable, not a magic number that will save the planet from the consequences of climate change.

Mann does see a little good news. Global carbon emissions have flatlined for the last three years, even as the global economy has continued to grow, he points out. This suggests a possible “decoupling” of the economy from carbon emissions, which Mann attributes to the dramatic growth in renewable energy around the world.

States, municipalities, communities and many large corporations, including some in the energy sector, are moving ahead with preparations for a low-carbon, renewable energy future, despite the movement backward under the Trump administration, Mann notes.

Related: Trump is ending Obama-era emissions cuts. How will CO2 emissions change?

Still, flatlining emissions won’t be sufficient. “As long as we're flat, we're still loading the atmosphere with carbon. We've got to bring those emissions down to zero," he maintains.

For now, the world still has a “carbon budget,” Mann says. Nations can still afford to burn a certain amount of carbon and keep warming below the dangerous 2 degrees Celsius/3.5 degrees Fahrenheit threshold. “If that's the goal — and that seems to be the goal that's been agreed upon by the nations of the world — we can still do it. Our own studies show that there is a path forward.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.