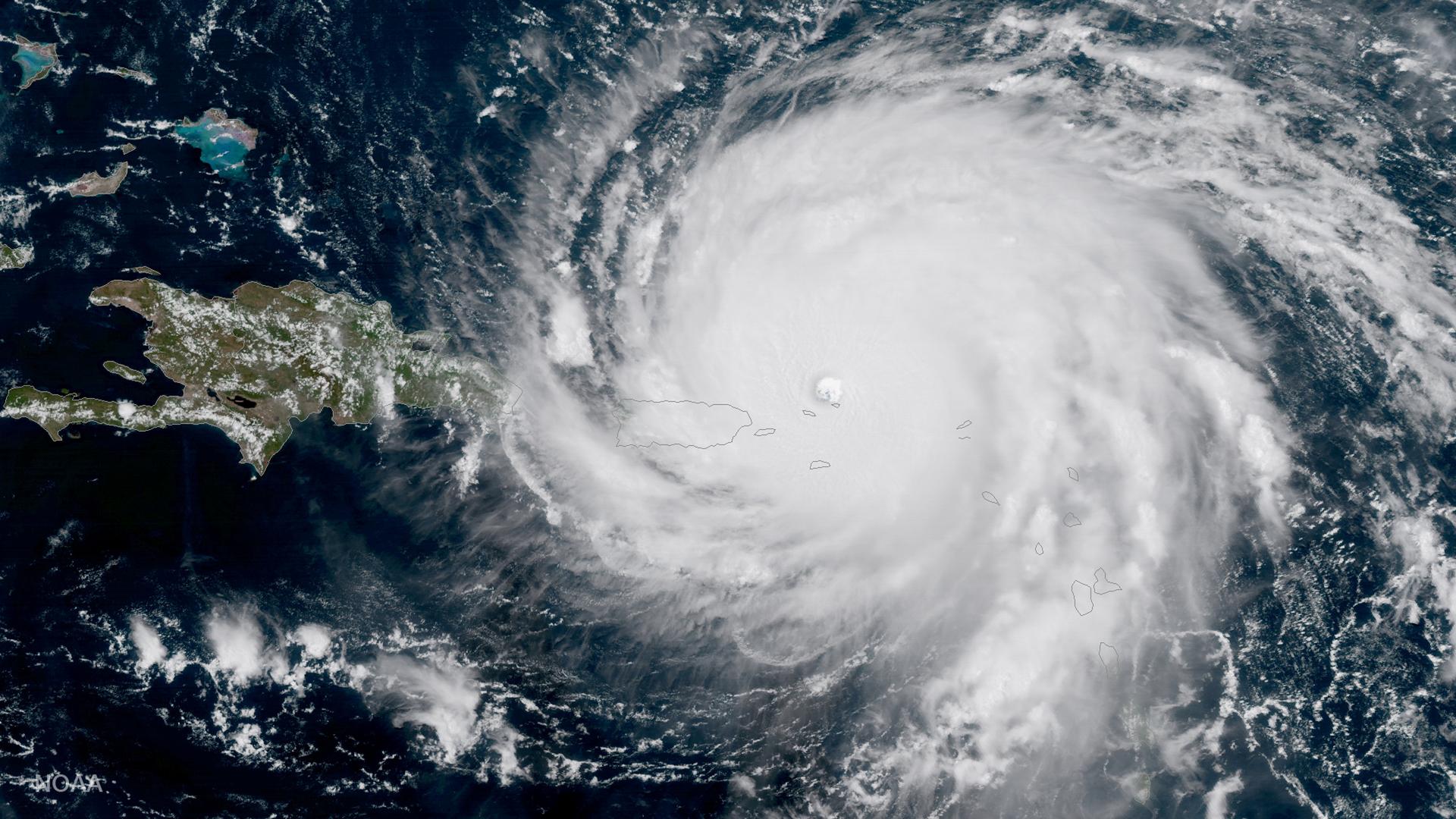

Hurricane Irma, a record Category 5 storm, is seen approaching Puerto Rico in this NOAA National Weather Service National Hurricane Center satellite image taken on September 6, 2017.

Another week, another Atlantic storm that weather watchers are calling "unprecedented."

Hurricane Irma slammed into the eastern Caribbean and Puerto Rico with 185 mph winds on Wednesday while millions in Haiti, Cuba and Florida fled or hunkered down in anticipation of the storm’s arrival later in the week.

Meanwhile, residents of Texas and Louisiana are still drying out and surveying the damage after Harvey dumped record rains on the region last week.

There's a lot of plain old bad luck involved in these back-to-back tempests setting their sights on the southeastern US barely a week apart. But the one-two punch of off-the-charts storms has a lot of people wondering whether it’s also a sign of climate change at work.

The unsatisfying answer is Yes, No and It’s the wrong question.

Climate change does have something to do with the destructive power of these two storms. In the simplest terms, rising levels of greenhouse gas pollution in the atmosphere is trapping more heat, and heat is what fuels storms.

But as with all weather phenomena, the genesis of hurricanes and other tropical storms is extremely complicated, and much of it comes down to the randomness of nature.

Big storms emerge in the tropical Atlantic and Pacific every year, and always have, including some very big ones that we barely notice because they never make landfall. Some years there are more, some years fewer, and there is a huge number of factors involved in when they develop, how strong they get and where they go.

It’s also not uncommon for tropical storms to be stacked up across the Atlantic at this time of year.

So, nature cooking up these two storms and sending them in roughly the same direction just about at once is pretty much just the luck of the draw.

Remember also that while they’re both the same kind of storm, they’re very different in their particulars. With Harvey, the worst effects came from massive amounts of rain — a record amount for the Houston area. With Irma, at least as of now, the big concern is wind — some of the highest and most dangerous winds ever recorded for a storm in this part of the world.

Again, to a large degree, the randomness of nature at work.

But what about that Yes to a role for climate change?

While the two storms are natural phenomena, they’re taking place in a very different environment than they would have just a few years ago.

Remember, greenhouse gas pollution makes the Earth hold more heat in the atmosphere and the oceans — more energy that leads to more powerful storms.

Warmer air can also hold more water, which in turn means more rain. Climate scientists say very warm water in the Gulf of Mexico basically pumped a lot more water into Harvey and made that storm’s rainfall worse than it would otherwise have been.

Finally, warmer air and water are also contributing to rising sea levels, which in turn bring higher storm surges — higher water gets pushed farther inland.

So the answer to the question “are these unprecedented back-to-back storms a sign of climate change,” is No, nature cooked them up, and Yes, climate change almost certainly made them worse. They are a product of a nature-plus.

Climate is what you expect, a scientist once told me, while weather is what you get. But what we expect is changing because of human activity, so what we get is changing too.

Extreme weather has always happened and always will. Climate change doesn't cause a hurricane or a blizzard or a drought. But it likely does make many of them worse.

The better question when it comes to climate change and extreme weather events isn’t about cause, it’s about influence. How much might climate change have altered the odds of a particular event becoming as bad as it was, and having the impact that it did?

Scientists are actually getting pretty good at answering that question soon after many extreme weather events. That’s important work, but it also shows how mired we still are in the false debate over whether climate change is real, and dangerous. Scientists have to keep proving it over and over again.

We know that climate change is here, and we know that it’s going to get worse and that there will be a lot more Harveys and Irmas and unnamed floods and heatwaves and droughts that will cause a lot more damage than they otherwise would have.

That’s why virtually every nation in the world agreed two years ago — now minus the US — to face the challenge, try to dial back emissions to reduce the damage and pump resources into helping get ready for what we know is coming.

Among other things, that means seriously evaluating the risks in vulnerable places like Houston and Miami, and perhaps redesigning communities to better protect them and their residents and businesses from the worst effects of both extreme weather events and the daily creep of a changing climate. In some cases, it might even mean helping people and communities move away from the most vulnerable places.

Where and how to do those things are tough questions. When it’s worth diverting scarce resources from other priorities is another one. How we’ll deal with the emotional and social impacts of all of these changes is yet another. Along with more extreme weather, climate change is bringing a raft of tough questions that we’ll be reckoning with for generations.

But in 2017, Is it affecting our weather? isn’t one of those tough questions anymore. It’s an easy one.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?