Harvey may have caught Texas by surprise, but other places have been getting ready for more extreme weather

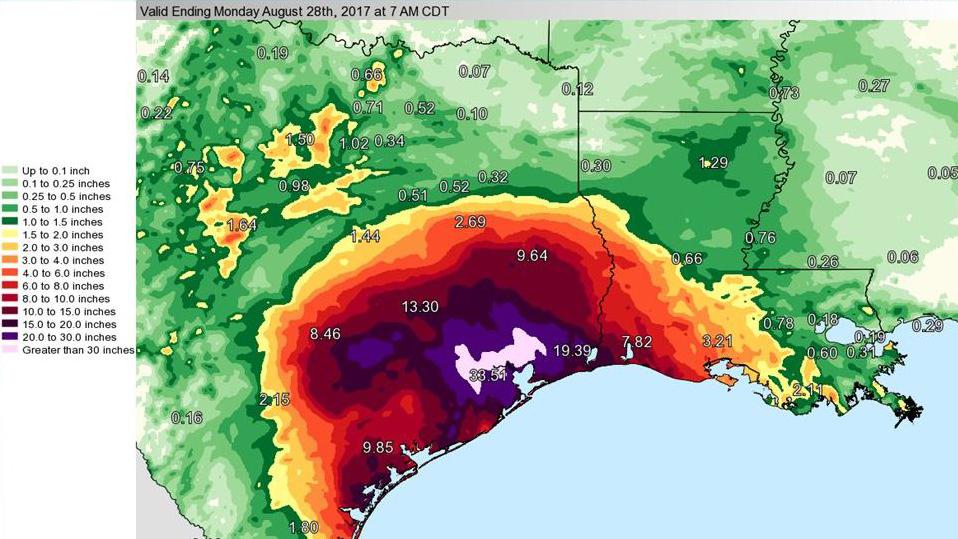

"So much rain has fallen," the National Weather Service tweeted about Harvey on Monday, "we've had to update the color charts on our graphics in order to effectively map it."

We don't know how much the epic flooding from Tropical Storm Harvey in Texas has been influenced by human pollution of the atmosphere, but the storm has likely been worse than it would’ve been generations ago, before we started pumping massive amounts of carbon into the air.

“Harvey was almost certainly more intense than it would have been in the absence of human-caused [global] warming,” writes leading atmospheric scientist Michael Mann, of Penn State University.

It’s a variation of an increasingly common story around the world, and it comes down to simple physics. Carbon pollution traps more of the sun’s heat — more energy — in the air and oceans. Warmer water leads to more evaporation. Warmer air can hold more water. And more water in the air “creates the potential for much greater rainfalls and greater flooding,” Mann says.

The trend is similar with heat and drought.

“[Recent] heat waves in India, Pakistan, China, Europe, Africa, Americas — in almost every case now we see that our emissions are making the events more intense or longer-lasting,” says Katharine Mach, who runs the Environment Assessment Facility at Stanford University.

Bottom line, says Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, “climate change just makes all of the weather events a little more extreme than they otherwise would be.”

The calamitous events of this week in Texas might suggest that we’re at the mercy of this new era of supercharged weather. But Mach, who focuses on how countries and communities around the world can respond to the growing threats from climate change, says it doesn’t have to be that way. She says many places are taking the threats of increasing severe weather events very seriously and rising to the challenge.

The Netherlands, for example, “has a top-to-bottom risk management approach” to climate threats, she says. France responded to a deadly extreme heat wave in 2003 by developing an early warning system and setting up cooling centers, which Mach says helped the country better ride out another heat wave three years later.

And then there’s New York City after superstorm Sandy.

“That event in many ways was a trigger for building back better,” Mach says. The region has been “thinking about everything from flood insurance, retreat among some communities, raising up boilers in hospitals so that critical infrastructure is safe, and even reimagining what the cityscape might look like so that it's more resilient.”

But Mach says ambitious action on climate isn’t restricted to high income countries.

Bangladesh, for instance — among the world’s poorest countries — has responded to the growing threat from cyclones that regularly hit the country by “developing protective structures so that they can raise up livestock and keep them safe, and also tapping the power of communities to provide early warning when a storm is coming.”

Mach calls those changes “very compelling” and says they have made a big difference in storm mortality in the country.

She says similar strides are being made in parts of Africa.

“We … see it in terms of community-based adaptation across the African continent,” Mach says. “Some of the most ambitious city-scale action, for example, has happened in Durban, South Africa. We see communities … coming together to think about what does [climate change] mean for planning for increased risk of flooding in some places, increased risk of drought in others. And [these are] communities that are already more on the margin,” compared to here in the US.

A big theme in adaptation, Mach says, is that “not all poor people are vulnerable and not all vulnerable people are poor.”

And not all places that have the resources to respond well to the threat have been. Texas itself is a prime example. It’s one of the most vulnerable places in the country to the effects of climate change, from raging floods to searing heat. But the state’s leaders have generally rejected any concern about climate change, and the state has taken very little action to prepare for it.

“We're already too late in some respects,” former state environmental regulator Larry Soward told The World in 2014.

Soward served under former Texas governor Rick Perry, who while in office rejected the overwhelming scientific evidence for human-caused climate change, and who now leads the US Department of Energy. But Soward parted ways with the Texas Republican establishment on climate change.

“If we don't start doing something today, we are going to have significant costs, in economic damage, property, lives, environmental damage, that could have been avoided to some extent, ” he said at the time.

Texas’s reluctance up to now to squarely face the risks of climate change drives home another key lesson from Mach’s work: that the barriers to climate change adaptation aren’t just about resources.

“In some places it's very much [about] financial capital,” she says, “do locations have the money. In other cases, the barriers… are more social or ideological, for example not paying attention to the way that risks are changing even if the scientific capacity is there to evaluate them.”

And Mach says the US federal government is moving in that direction.

“President Trump just rolled back an Obama era effort … to take into account flood risk for federal infrastructure,” Mach says. “That kind of backsliding it's not smart management or ambitious management in a changing climate.”

Neena Satija of the Texas Tribune contributed to this report

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?