Young, undocumented and trying to ‘keep my sanity’

Erick Silva Palacios, a 23-year-old high school teacher in San Jose, California, came to the US from Mexico when he was a child, without papers. Since 2012, he has worked legally in the US thanks to a program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which a group of Republican-led states now threaten to stop.

Erick Silva Palacios is at his kitchen table, glued to his laptop. He’s watching a press conference with Dick Durbin, the Democratic Illinois senator, and a bipartisan group of senators introducing the latest version of the Dream Act. It would help people like Silva Palacios. He is a 23-year-old high school history teacher who came to the US, without papers, from Mexico when he was 5. The proposed legislation would give him a road to citizenship.

But Silva Palacios knowsthe Dream Act is a long shot. The show of support, though, means a lot right now.

"The timing couldn’t be any better," says Silva Palacios. "There has been a lot of talk about how a lot of different states, and a lot of different senators, are putting pressure on the Trump administration to get rid of DACA."

DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, was implemented by Barack Obama by executive action in 2012. It lets some undocumented immigrants who came to the US as minors (often called Dreamers) work legally, on two-year, renewable permits. But DACA is under threat, and that has many of the more than 750,000 people enrolled in the program nervous, including Silva Palacios, who enrolled in DACA the year it was introduced.

"DACA gives us Social Security numbers, allows us to get jobs, allows us to get driver’s licenses in certain states," he says.

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump said he would end DACA on "day one." But, as president, he has given mixed signals, and the program is still chugging along. Now, attorneys general from Texas, Alabama and eight other Republican-led states warn that they will sue the Trump administration if it does not rescind DACA by Sept. 5. They say it rewardspeople who came to the US illegally — and it’s unconstitutional. It’s a threat with teeth, and members of the Trump administration, including Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly, are not saying that they will defend DACA in court.

It is keeping Silva Palacios on a roller coaster that is intensifying.

"We’ve seen a lot of other marginalized communities get hit hard, and we’re kind of not sure when our turn is going to be," he says. "So, you don’t feel safe anymore. It always feels like we’re tiptoeing our way to 2020, we’re tiptoeing our way to, hopefully, a new president.”

Some days, Silva Palacios wants to hide from the news. "Sometimes you just have to turn the other way. It doesn’t mean you’ve given up, don’t care anymore; it means for right now, I’m going to keep my sanity, I’m going to keep my cool," he says.

But on other days, he wears a black T-shirt with big, white letters, which read, "undocumented, unafraid and unapologetic."

"Some might say that I committed a crime, and so I’m like boasting about committing a crime," he says. "I think it’s just me putting a face to the name."

It has taken awhile for Silva Palacios to feel this confident. He’s known he was undocumented since he was a kid.

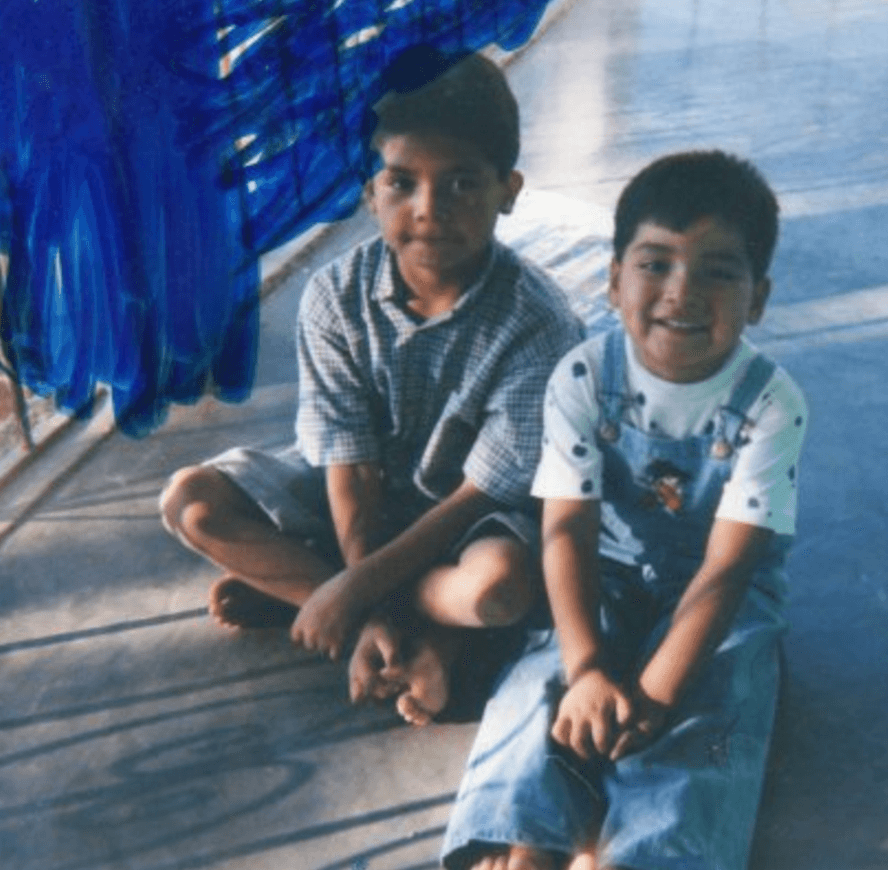

"We crossed [the border] in a car with fake documentation," he says. "So, we pretended to be asleep, and they presented documentation of other US children."

He knew he had to be careful; he was taught to duck when police cars went by in the neighborhood he grew up in San Jose, in a heavily immigrant part of the city.

"So, as kids we learned to avoid police, we learned to be wary," he says.

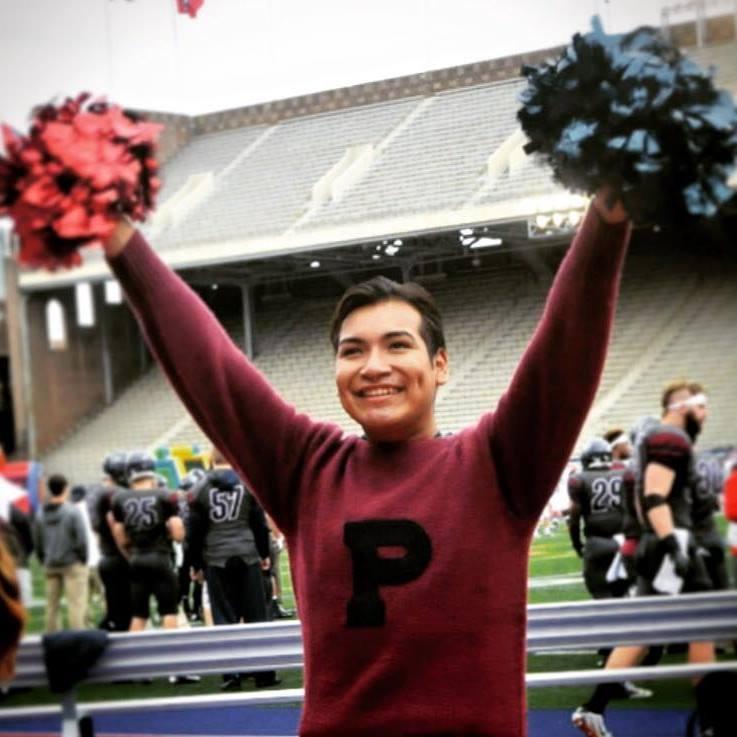

But Silva Palacios has done well. Last May, he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in the same class as Tiffany Trump.

"Donald Trump’s daughter sat four people down from me during our commencement ceremony," he says.

Donald Trump was also in the same audience as Silva Palacios's dad, an undocumented construction worker from Mexico.

"Just seeing my dad in the audience and seeing Donald Trump in the audience, I felt like I was able to give my parents the biggest thank you I could give them," Silva Palacios says.

He also realizes that plenty of people think that he should go back to Mexico. He recalls a conversation he had in Wisconsin with a friend’s mom who voted for Trump.

"She just asked what I do and all that jazz," he says. "And by the end of the conversation, she realized that you don’t necessarily hear about undocumented immigrants who are working and contributing to society because that’s not going to drive the message forward of us being bad people."

He says she also asked him why he couldn't just go through the process to make him a US citizen.

"That always seems to be such an easy option to someone who isn’t undocumented. Well, just get in line," Silva Palacios says. "But it’s backlogged. They’re still working on cases from 1996."

When asked about how he sees his future in the US, Silva Palacios says, "I want what everyone else wants. I want the nice house, a white picket fence, the dog!"

His parents, however, are tired of being undocumented. His mom returned to Mexico three years ago, his dad is seriously considering going back. It's leaving Silva Palacios on his own, living with fellow teachers in a one-story home in San Jose. It's on a quiet street not far from where he grew up, and he points out his favorite part of his home: the front yard, with its palm tree and picket fence. Home, he hopes, for good.