How Iranian scientists at one Harvard lab are reacting to Trump’s immigration restrictions

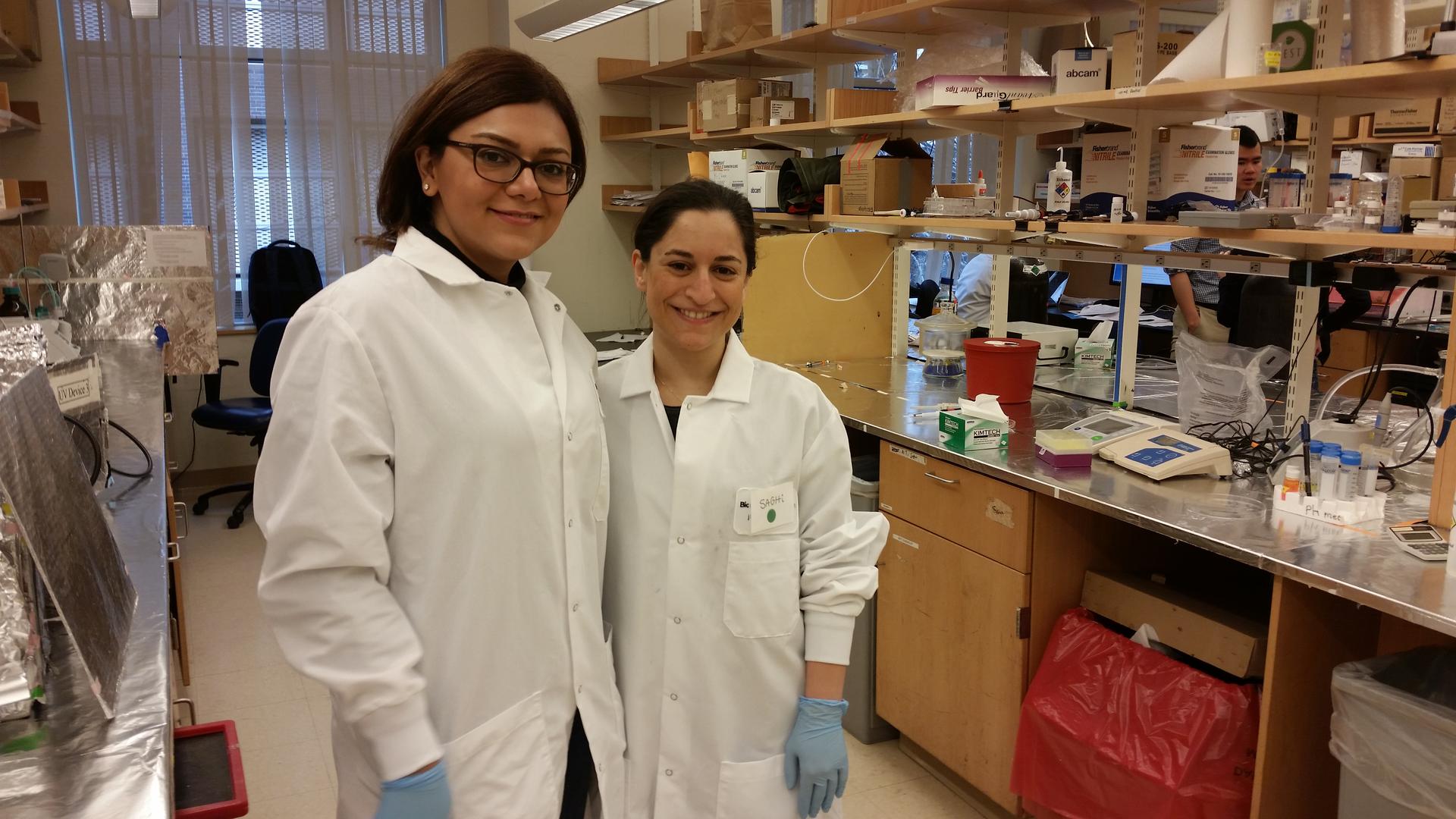

Dr. Elmira Jalilian, left, and Dr. Saghi Saghazedhi work at Harvard's Tissue Engineering Lab.

Scientists from Iran loom large in the history of American innovation.

In the 1980s, an Iranian American doctor, Gholam A. Peyman, helped invent laser eye surgery. In 2014, Maryam Mirzakhani became the first Iranian and the first woman to win the highest award in mathematics — the Fields Medal. And those are just a couple examples. Last year, 12,000 students came from Iran to the United States.

With that history in mind, Professor Ali Khademhosseini was disturbed to learn about President Donald Trump’s executive order barring nationals from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US. “I was very shocked,” said Khademhosseini, a US citizen who was born in Iran, one of the listed countries. “Particularly because my own wife, who is now a green card holder, is affected by this.”

Khademhosseini has spent the past few days discussing the new restrictions with colleagues, who come from all over the world. There are lab members from China, Korea, Italy and Iran, among other countries. Thanks to the executive order, a shadow of uncertainty has fallen over the Iranians who work there.

“The visa has never been easy for Iranians,” said Saghi Saghazadeh, a lab scientist on a work visa who is affected by the travel ban. “Is this just a direct way of saying, ‘leave our country’?”

Saghazadeh, who also studied in France and Belgium, said she’s willing to work elsewhere if she must. “If I’m not welcome here, I will go wherever else that I am welcome. I don’t know, Canada, Australia, Europe. Wherever I’m not seen as trouble.”

More than a dozen scientists who were waiting to join Khademhosseini’s lab are now unsure if they’ll be able to come. And those who already work there have been rethinking their plans. One scientist said her husband is currently visiting the US. He’s worried that if he goes back to Iran, he’ll be separated indefinitely from his wife.

Currently, several court cases are challenging the executive order, but it’s not clear whether different policies will emerge for dual citizens, green card holders, and scientists on work visas. Khademhosseini is worried that American science as a whole will suffer if these issues aren't quickly resolved.

Ali Tamayol, a doctor who works at the lab, said he’s worried he made a mistake when he came to the US from Canada four years ago. “I didn’t have that feeling a few weeks ago,” he said.

Tamayol said he is upset with the US government, but he isn’t angry at Americans in general. “I know that they supported us. We saw on the news,” he said, referring to airport protests across the country. But Tamayol did express surprise that the government would allow such a broad immigration and refugee restriction. “I want to say I’m disappointed.”

Ever since the executive order, it’s been tense in the lab. But ask these scientists about their work, and the mood suddenly lightens. “So like when you are asking about this, we have a smile on our face, because this is what we like to talk about,” Saghazadeh said.

She explained how her colleagues grow different kinds of human cells, which they then suspend in a special gel. The gel can be loaded into a 3-D printer. The result? 3-D printed human tissues.

Her lab mate, Elmira Jalilian, said she came to the United States because she was passionate about discovery. “We work hours and hours in the lab, even on Saturday, Sunday,” she said. “We are working so hard to push things forward.”

Her biggest concern is that her immigration status could make it impossible for her to keep doing research here. “This is something that breaks our hearts,” she said.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the last name of Elmira Jalilian. This version has been corrected.