They gave her the keys to the mosque — and now she wants to open its doors to the neighborhood

“For the most part, the building is closed,” says 31-year-old Alyssa Ratkewitch of her Brooklyn mosque. “And that’s something I really want to turn around.”

Ever so carefully, Alyssa Ratkewitch pulls out an old Quran from the shelf. She cracks it open, exposing the aging, fragile pages covered in handwritten Arabic script.

“This is one of the handwritten Qurans we have,” the 31-year-old native Brooklynite says. It’s older than most anyone can remember, and is one of the many treasures brought to this modest Brooklyn mosque by Ratkewitch’s relatives at the beginning of the last century.

Ratkewitch is now the caretaker of that legacy. A third-generation American of Lipka Tatar descent — the granddaughter of an imam — she was given the keys to her community’s historic mosque just last year. She is the youngest member of its governing board by decades. She has never had a formal religious education, but it is Ratkewitch who is beginning to chart the future of this mosque, which is struggling to find a purpose as its historically-insular congregation dwindles and disappears.

“It’s been steadily declining since its heyday in the 1950s,” Ratkewitch says. “When I was younger, 20 or 30 years ago, we would get maybe 40 people in. Certainly, I’ve seen the membership, or at least the attendance, decline sharply.”

The Lipka Tatars are a Muslim Turkic ethnic group with 600-year-old roots in lands now split between Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. Several hundred of them immigrated to New York beginning in the late 19th century. In 1907, the community formally organized, and later turned an empty church into a mosque. By the 1950s, the mosque was full each Friday for prayers and social activities. In the basement, imams like Ratkewitch’s grandfather gave religious lessons to kids and taught them Arabic.

“The place was packed with people,” recalls Marion Sedorowitz, who grew up in the mosque and now sits on the board. “It was just amazing, how many people could fit into it.”

For much of its existence, the congregation kept a low profile. Brooklyn’s Lipka Tatars did not interact much with other Muslim groups — with the exception of the few Albanian and Turkish families that joined the congregation — and also never built strong ties to other Polish, Lithuanian or Belarusian communities.

“I can’t really explain it that well,” Ratkewitch says. “There is just this old mentality of being almost isolationist. And in their mind, that is safe. That will keep our members together, and keep the identity from being changed.”

Lipka Tatars largely stopped immigrating to the US during the Cold War, and attendance at the mosque plummeted when younger generations of American Tatars moved away or married non-Muslims. The mosque’s membership still represents around 100 families, but the community only gathers on holidays or for funerals. For the few religious services, attendance is seldom more than a dozen people.

“For the most part, the building is closed,” Ratkewitch says. “And that’s something I really want to turn around.”

It is the slow generational shift in the mosque’s leadership that has started to open the mosque up. After the last Lipka Tatar imam retired, the congregation brought in a Turkish imam. Earlier this year, at Ratkewitch’s suggestion, the community opened its doors on Eid, which Tatars call Uraza bayram, and held a barbecue for the neighborhood, a historically Italian part of Brooklyn.

“It got everybody excited about having people around again,” Ratkewitch says.

Among the other ideas Ratkewitch has: host interfaith lectures; become a place where imams can hold religion classes for local Muslim kids of all backgrounds; use the facility to offer a space for Muslim women to do yoga; or hold more Lipka Tatar cultural events, like cooking classes.

“If we can keep it open, that’d be great,” Ratkewitch says. “I think social programs, whether or not they are directly tied to religion, would be a good idea. We did have a couple of cooking classes — of those old dishes from our grandparents — and we’re going to keep doing that because it was really nice to see, because it was the best turnout we’ve gotten in years.”

“The first time we did that, we had around 40 people come. And it was like, ‘Wow, yeah, this place used to be full, and it can be that again.’”

Touring the mosque, it is easy to see what is at stake. Hung on walls around the building are faded decorations made by congregants long ago. The corner bookshelf in the basement, adorned by a sign that reads “Our Moslem Library,” is increasingly full of old books and notebooks of religion lessons that are mailed to the mosque when elderly members pass away.

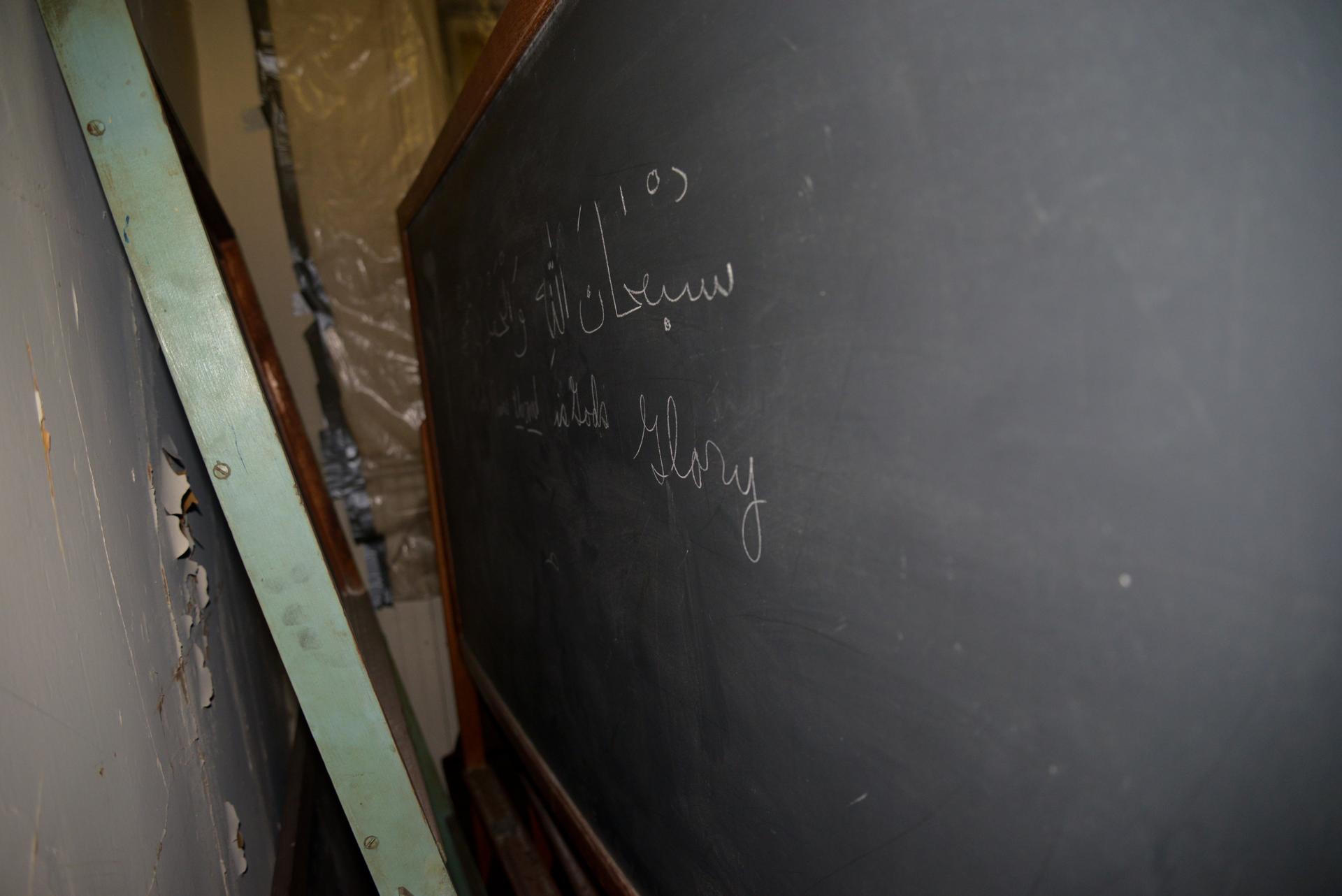

Ratkewitch pulls open a closet door. She moves old chairs and a dusty fan out of the way, revealing a chalkboard. On it, in smooth white letters, are lines of Arabic, left over from one of her grandfather’s religion lessons, likely from the 1960s.

Within this mosque is proof of Islam’s deep roots in the US, and the story of a proud community of immigrants who built an American identity around their faith.

History: More American than apple pie, Muslims have been migrating to the US for centuries

“I don’t want to lose our ancestry,” Sedorowitz says. “The core of religion, the core of family — how it came across here and stuck all those years — it’s all got to mean something, and I don’t want for that to get lost.”

“If [these changes] bring in people for services, I would be very happy,” Ratkewitch says. “If it doesn’t, and it just remains a space that is a standing piece of history of New York and of Tatars, then that’s cool, too. I would accept both of those.”