Descendants of Syrian immigrants to North Dakota stand before a replica of one of the first mosques in the US, built in the city of Ross around 1930.

Muslims have been coming to the US for centuries, but you wouldn’t know it by the intense debates that continue to surround the movement of Muslims across international borders.

Republican presidential candidates Sen. Ted Cruz and Donald Trump have called for the US to effectively ban Syrian refugees from entering the country. The South Carolina Senate passed a bill that would require all refugees to register with the state, subjecting themselves to surveillance. On social media, the hashtag #StopIslam trended internationally in the hours after the Mar. 22 terrorist attack in Brussels.

Together, these reactions contribute to the idea that Muslim migration to the US is somehow distinct from America’s history as a “nation of immigrants.” Columnist Mark Nuckols summarized the sentiment when he wrote in Townhall about “problematic immigrants” to the US.

The “most problematic,” he writes, are Muslims from the Middle East and Africa. “This most recent wave of immigrants are often more resistant to easy assimilation and more reluctant to accept this country as truly their own,” he says.

In truth, Muslims have been part of this country since before the thirteen original colonies even declared their independence and became a nation. The examples below offer a glimpse of the long history of their migration and contributions to the US.

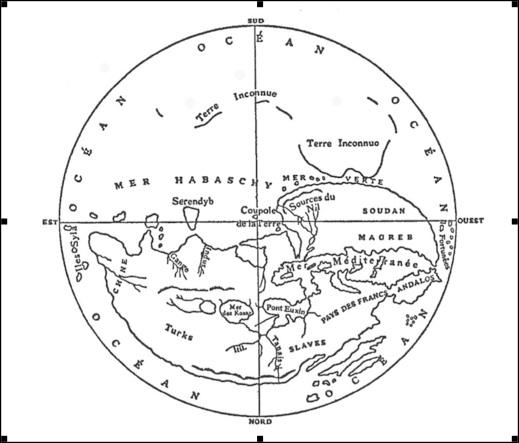

Muslims were among the first to explore the “New World”

Individuals like Christopher Columbus are often recognized as among the first to “discover” the Americas (despite, of course, the long presence of the indigenous).

But those explorations would not have been possible without Muslims.

Historian Leslie Brout Jr. notes in his book The African Experience in Spanish America: 1502 to the Present Day that many Muslim men accompanied European travelers clamoring to “discover” the Americas in the 1500s. Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Hernán Cortés, Pánfilo de Narváez, Pedro de Alvarado, Francisco de Montejo, and other conquistadors all brought Muslims with them to aid in their early expeditions in the Western Hemisphere.

For example, a Muslim man named Estevanico was sold into slavery in the 1520s and brought to the Americas to aid Spain’s exploration of present-day Florida. Although he was a slave until his death, Brout writes that Estevanico became famous for completing an eight-year journey on foot from Florida to Mexico City.

The labor of enslaved Muslims helped build the United States

As historian Sylviane A. Diouf writes in her book Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas, Muslim men, women, and children were among the first people taken by force from their homes in West Africa in the Atlantic slave trade.

It’s estimated that between 10 and 15 percent of all Africans forced into bondage in the United States were Muslims. These individuals, many of whom were among the most educated and renowned in their homelands, were forced to work as slaves in the Americas. Several of them published narratives about their time in captivity.

Omar Ibn Sayyid, for example, was taken from his home in present day Senegal and forced into slavery in South Carolina around the year 1770. In 1831 he published his autobiography in Arabic, which was later translated into English.

Sayyid’s autobiography reveals in his own words his experiences being taken from his home, his life under slavery in the United States and his devotion to Islam. Today, a mosque in Fayetteville, North Carolina is named in his honor.

In his book Muslims in America, historian Edward Curtis describes the experience of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, who became known as Job Ben Solomon after he was taken from West Africa in 1731 and sold into slavery to a tobacco farmer in Annapolis, Maryland.

Solomon was able to escape slavery after less than three years of bondage. He could read and write in Arabic, so he wrote a letter to his father with the hopes that he might send money to ransom his freedom. His father never received the letter. However, the letter did finds its way to the hands of James Oglethorpe, the founder of Georgia, who had it translated into English.

Oglethorpe was so impressed with Solomon that he purchased the freedom bond himself.

Slavery ends, Muslim influence continues

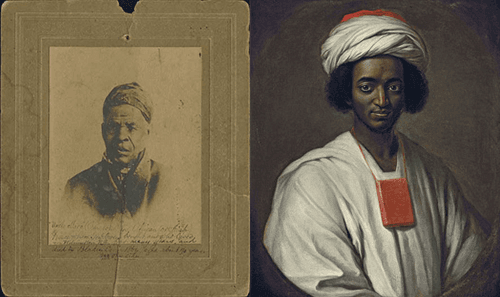

[[{“fid”:”100130″,”view_mode”:”image_on_left”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Cover of \”Islam in America” showing author in a turban and suit”,”height”:1148,”width”:826,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-left”,”data-delta”:”3″},”fields”:{}}]]

Muslims played important roles in securing a Northern victory in the United States Civil War and bringing about the end of slavery. Curtis’s Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History explains that nearly 300 people with Muslim last names fought in the Civil War.

Several became officers, including Moses Osman, a captain in the 104th Illinois Infantry. After being subjected to slavery in Turkey, Russia, and the US when he was forced to serve a European traveler who crossed the Atlantic, Mohammed Ali ben Said fought in the Civil War from 1863 to 1865 and earned the rank of sergeant in the Union Army. After his emancipation, Said went on to travel the world before settling in Alabama. He published his autobiography in 1873 before passing away in 1882.

While emancipation allowed former Muslim slaves to practice their religion more freely, they were not the only ones who practiced Islam in the US after the Civil War.

Alexander Russell Webb, born in 1846, was a middle class white Protestant who converted to Islam in 1887 after traveling the world in his capacity as the US Consul to the Philippines. When he returned to the US in 1893, he started a newspaper called “The Moslem World,” published a book called Islam in America and was selected to be a representative of Islam at the Chicago World Fair.

Nativism and exclusionary immigration laws took hold in the early 1900s, but Muslims lived all over the country

With the turn of the 20th century came the rise of anti-immigrant feelings among Americans. Nevertheless, Muslim American communities continued to grow. In North Dakota, for example, Syrian and Lebanese Muslim immigrants worked as farmers in the Great Plains.

As part of the New Deal, the Works Progress Administration interviewed Mike Abdullah, a Syrian native, about life in North Dakota. Abdullah and his fellow community members in North Dakota were practicing Muslims whose experiences mirrored those of many farmers who worked the land in the American heartland from the 1900s through the middle of the century.

[[{“fid”:”100133″,”view_mode”:”image_on_right”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Entry for \”Syrian””,”height”:832,”width”:489,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-right”,”data-delta”:”5″},”fields”:{}}]]Muslims lived and worked across the US. Historian Vivek Bald writes in Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian Americans that Muslims labored not only as farmers but also as industrial and service workers. They immersed themselves in Creole, African American and Puerto Rican neighborhoods in New Orleans, Detroit, Baltimore and New York City. The growth of these diverse communities continued despite the passing of laws that didn’t bode well for Muslims hoping to come to the US.

The Immigration Act of 1917 barred immigration from Asia, and the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 introduced numerical quotas that restricted the entry of immigrants according to their country of origin. Many countries with sizeable Muslim populations received low quotas and Muslims from Asian countries were excluded outright.

The Hart-Cellar Act of 1965 eventually eliminated national origins quotas and made it easier for Muslims — at least those who were skilled and professional workers — to migrate to the US. This landmark legislation was just part of the continuation of Muslim migration to the US — not the beginning.

These examples only scratch the surface of stories about the long history of Muslims in the United States. Feel free to share more stories and histories in the comments. This story was produced in partnership with the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota.