Recycling sewage into drinking water is no big deal. They’ve been doing it in Namibia for 50 years.

The Goreangab water treatment plant uses a process that partially mimics nature to turn sewage from Windhoek’s 300,000 residents back into potable water. It opened in 1968 and was the first such plant in the world.

On the outskirts of Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, there’s a huge, churning vat of nasty brown liquid. It's so stinky that my guide, the man who runs Windhoek's water department, tells me I might want to stay in the car.

But this is what I came to see — raw sewage, on its way to being turned back into drinking water.

The Goreangab waste treatment plant is where most of the wastewater from Windhoek’s 300,000 residents ends up. But it’s not your run-of-the-mill sewage plant. It’s the first stop in the city’s pioneering water recycling system.

Cities around the world are wrestling with whether they should build facilities like this. But here, in the middle of a desert in a remote corner of southern Africa, they’ve been recycling wastewater for almost 50 years.

It’s cutting-edge technology, but it’s based on the humblest of creatures — bacteria.

“Everything is done biologically, by the organisms,” explains Justina Haihambo, a process engineer at the plant. The bacteria help digest the human waste and pull it out of the water, essentially mimicking what happens in nature but a whole lot faster.

Speed was important when the plant was built back in the 1960s, and it’s even more important today.

“The plant was originally designed to treat 27,000 cubic meters [of sewage] a day,” says Haihambo. “But now sometimes during peak hours, we have around 41,000 cubic meters a day. Way more than it was designed for.”

That’s because Windhoek is bigger now than it was back then, and it’s again on the verge of running out of water from natural sources. The local reservoir, or dam, is almost empty.

“Our next rainy season is expected in January [or] February next year,” says water department head Pierre van Rensburg. “But we know before that the dams will be out. And we also don’t know how much rain we will get. We went through the last rainy season without having any inflow on the dams.”

The drought that’s ravaging much of southern Africa is hitting Namibia hard, too. But van Rensburg grew up here, and he says water was always scarce.

“I can remember similar to what we have now, not being able to water your lawn,” he says. “Having to bathe in the same bath as others, collecting every drop of rainwater to try and use it to keep some plants alive.”

Before the mid-1900s, Windhoek got most of its water from nearby springs. But they dried up, and without much rain, it seemed the only way to keep up with demand was by taking what at the time was the radical step of reusing the city’s wastewater.

These days, such a plan can bring howls of protest by consumers repulsed by the idea of drinking recycled sewage. But the technology pioneered here has proven safe.

Not that there was much public input at the time. Back in the '60s, Namibia was controlled by apartheid-era South Africa, and the government wasn’t much concerned with public opinion, especially with the majority-black population.

Today, though, no one I talked with had any complaints about drinking recycled water. And van Rensburg says locals are now proud to have pioneered the idea.

“If you talk about the cradle of water reclamation, potable reclamation, everybody comes and see this. This is where it all started in 1968.”

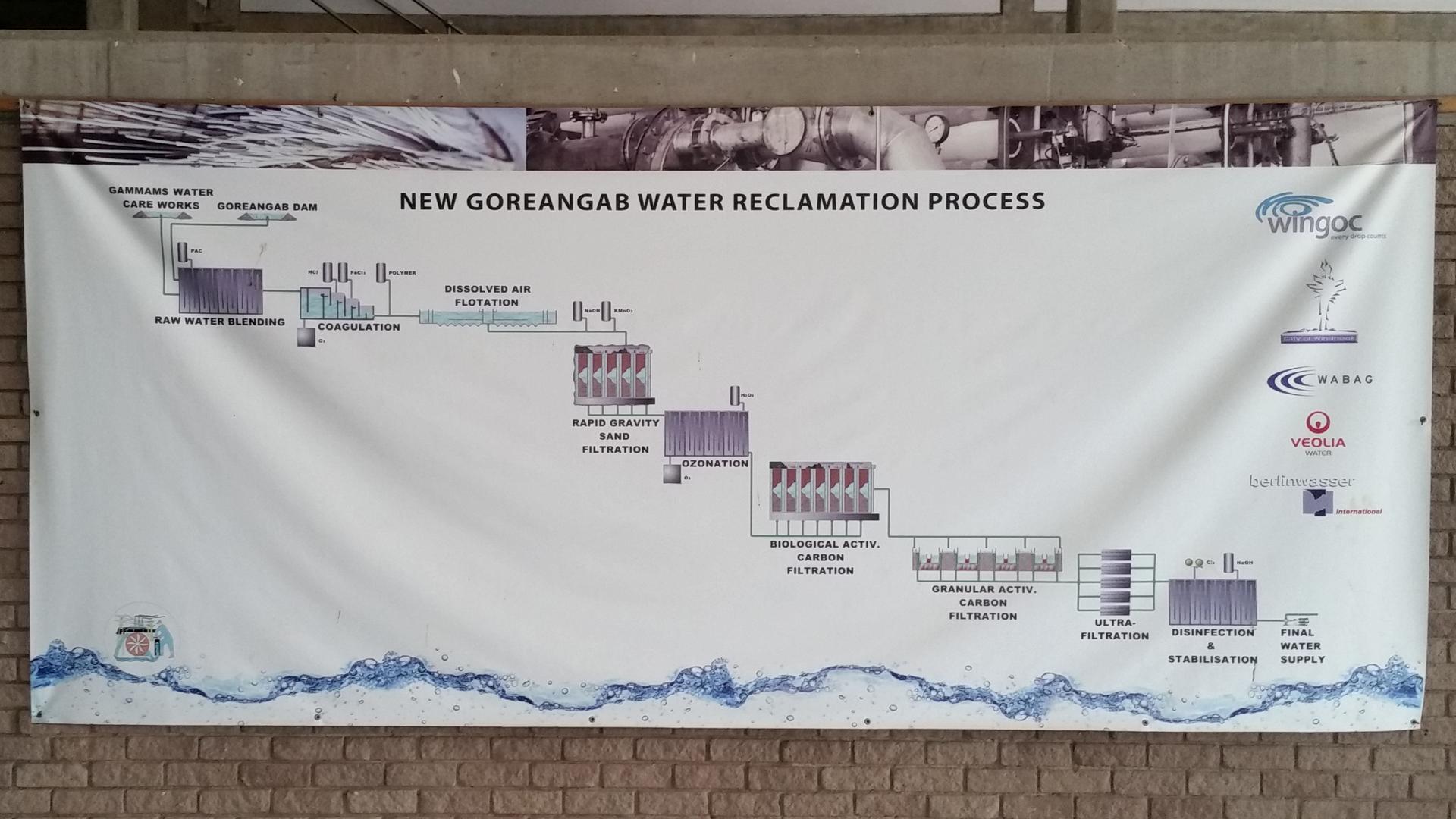

The plant’s been updated since then. Today, after the sewage we started with has already been cleaned to the point where most cities would just pump it back into a river or the sea, it’s sent off to be further purified with ozone and activated carbon.

Of course, it’s not like this pioneering plant helped make Windhoek a modern metropolis. Just outside Goreangab’s gates, there's a huge slum of corrugated tin huts.

It's strange to see such poverty right next to this cutting-edge facility. But van Rensburg says it actually makes a lot of sense. Namibia has struggled with basic needs, and necessity is the mother of invention.

“If you look at the world, the pressing need is always in developing countries,” van Rensburg says. “It's a fast-changing environment. So, you always have to be innovative to try and stay a step ahead.”

Van Rensburg thinks developing countries like Namibia can lead the world in innovation — if they can gain access to funding and skilled labor.

“The fact that an idea can be generated in a developing country, that can actually inspire a similar trend in a developed country, is definitely, in my opinion, something that can happen,” he says.

Goreangab gets a lot of visitors from developed countries facing water shortages. Experts have come from Australia, Singapore and the US to see where water reclamation started. All those countries now have their own sewage recycling plants.

This place doesn’t supply every drop of Windhoek’s water. The city still taps groundwater and harvests some of what does fall from the sky. But the future here may be even drier than the past, so water recycling is more important than ever.

And the people who work at and run this plant put their water where their mouth is. There’s a drinking fountain on the way out of the plant that burbles with clear, cool water.

“That is the product from this plant,” says van Rensburg. “It's 100 percent purified sewage water.”

I take a sip, then another. It tastes delicious. And I lived to tell the tale.

Related:

Can an Indian-American tackle India’s twin challenges of poor sanitation and lack of clean water?

In its worst water emergency since the Dust Bowl, California needs solutions fast

Desert Lunch: Coaxing Climate-Friendly Food from the World’s Driest Places