This doctoral student is building public toilets in India that also provide clean drinking water

Children drink water from the SHRI sanitation system.

When Anoop Jain graduated from college in 2009 and got a good job as an engineer, his parents figured he was set.

But then a year later, he left his engineering job to go to India to work in community development.

At first, he says, his parents, who are Indian immigrants, were "really nervous." But now, they're happy with what he's doing.

He's founded an organization called Sanitation and Health Rights in India (or SHRI) that builds public toilets in Bihar state, one of the poorest in India. SHRI works with local communities to end the practice of open defection, a huge public health issue in India. An estimated 600 million people in India lack access to toilets and sanitation.

SHRI now has four public facilities, and they hope to complete two new facilities by the end of the summer.

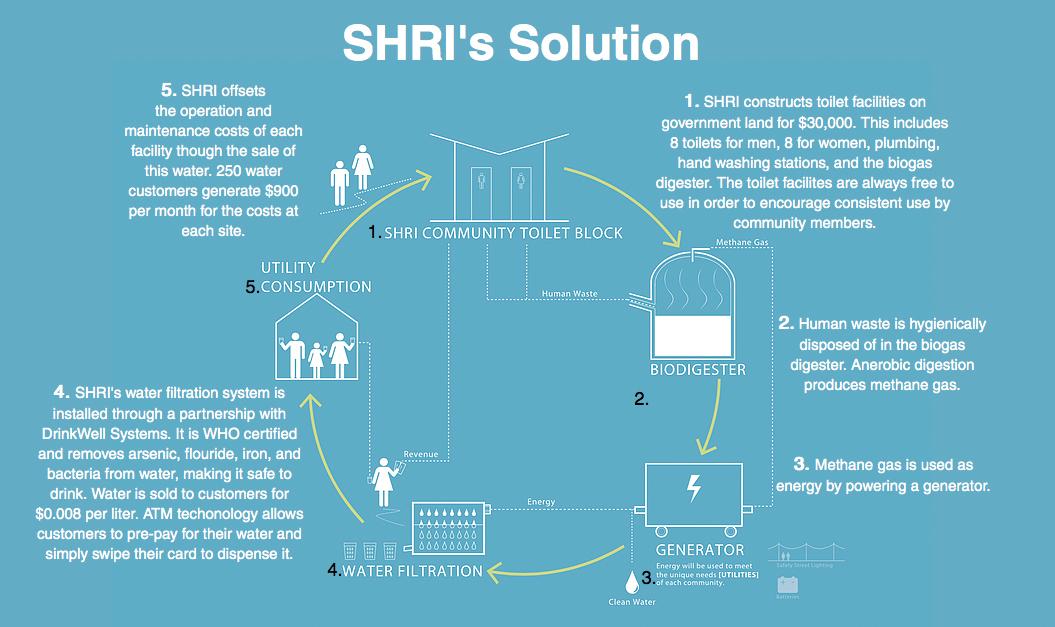

These toilets also serve another function: they provide clean drinking water. As the waste from the toilets decomposes in an underground tank, it produces methane gas, which is used to power a water filtration plant that supplies clean drinking water.

The Indian government, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has pledged to build millions of toilets to deal with the lack of sanitation. But just building toilets doesn't address the entire problem. Reports suggest that many people aren't using the government toilets, especially in rural areas.

Jain says his group assumes that people want to use toilets. One problem with the government toilets, he says, is that they have pit latrines that fill up with waste. People either have to pay to get them emptied or do it themselves. "No family wants to do that, especially in areas where the caste system is still so deeply entrenched," Jain says. "They don't want to be associated with the 'untouchable' caste, which in many parts of India is still responsible for emptying waste."

SHRI's toilets are free because they want to encourage people to use them. They sell the filtered water at a nominal fee to help fund the operation.

"So far we're seeing 3,000 to 4,000 men, women and children a day at our toilet facilities, and we sell over 100,000 liters of safe drinking water each month."

But he says working in India can be a humbling experience. In the US, "I consider myself a person of color," he says. "But when I'm in India, I am seen as an American" — essentially a white American.

He dresses like an American, and he speaks Hindi with an American accent.

Jain recalls one incident when he got into an argument with a group of young men in Bihar state who were harassing the workers building the toilets. Although the young men were from the Brahmin caste (India’s highest caste), they were also poor. And they started yelling at the workers.

"They were afraid that the low caste community was getting services and they would be left behind," Jain says.

When he tried to speak to the men in Hindi, one of them responded in English. "He was telling me that I didn't know what I was doing. He said 'my friends and I are all out of work. You're building toilets. Why don't you get me a job?' "

Jain says when he tried to explain that SHRI wanted to help the poorest of the poor, the young man shot back, "Who are you to decide who's poor here?"

Jain says he struggles with the fact that he's always an outsider, but he accepts it.

"Too often development workers begin to feel that maybe we are part of the community," he says, "and we're not."