If the multiverse is real, what does that mean for modern-day religion?

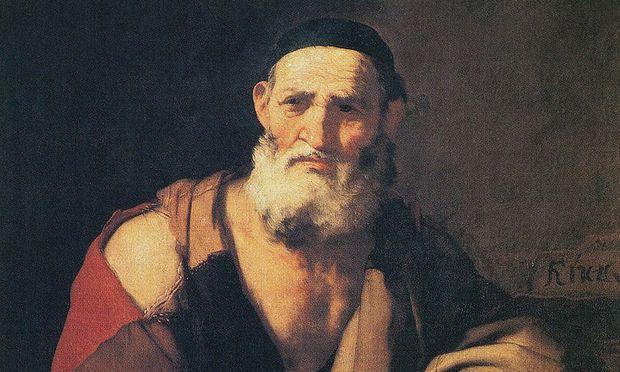

Leucippis, thought by many to be the father of atomist philosophy

There are lots of multiverse theories in play at the moment. They have names ranging from “the quilted multiverse” and “the inflationary universe” and “the ultimate multiverse.” It all feels exciting and new. But it's not as new as you might think.

Multiverse is defined as "a hypothetical collection of identical or diverse universes, including our own."

“The idea of multiple universes is about 2,500 years old,” says Mary-Jane Rubenstein, a professor of religion and philosophy at Wesleyan University. According to Rubenstein, long before nerds in pocket protectors were debating this stuff, nerds in togas were — the Atomist philosophers, of ancient Greece.

“For the ancient Atomist philosophers, the most desirable thing about what we're now calling the multiverse was that it got rid of the need for a god,” Rubinstein says. “If it is the case that our world is the only world, then it's very difficult to explain how everything is so perfect. How is it that sunsets are so beautiful?”

The ancient Atomists turned to the multiverse theory to explain the world’s perfections.

“Their explanation was that it's not the case that some anthropomorphic god or gods made the universe so that it was just perfect the way it is, but that actually our world was just one of an infinite number of other worlds that looked totally different from our world and that worlds were the product just of accident, of particles colliding with one another and randomly forming worlds and an infinite amount of space to play in,” Rubenstein says.

If the multiverse theory continues to grow in popularity it will, as with all new scientific theories and discoveries, present the world with new theological and philosophical problems.

“Every major development in modern western science since Copernicus has been advertised as this radical de-centering of our influence,” Rubenstein says. “In the pre-Copernican universe, the sun was at the center and we were so important, the story goes. And then Copernicus takes us out of the center of the solar system. And then Darwin takes us out of the center of the Garden of Eden. Freud takes us out of control of our own psyches. As science progresses, we learn that we are less and less important than we thought we were. … But of course it doesn't seem to be the case that these purported decentralizations of the importance of the human have in any way contributed to our feeling like we're insignificant.”

Rubenstein has written a book about the multiverse theory called “Worlds Without End: The Many Lives of the Multiverse.” She details some of the complications religions will have to deal with if the multiverse theory continues to gain ground.

“You do run into some fascinating theological problems. Things like, for example, if you are operating within a Christian framework, you would need to ask, ‘Well are there inhabitants of those other universes? And if there are inhabitants of those other universes, are they fallen or not right? Have they sinned? Do all creations fall? And if they have fallen, do they also need Christ to go there to redeem them,” Rubinstein says, “If that’s the case, then theology’s got a serious problem.”

This story first aired on PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen.