A way to save one of North America’s fastest animals

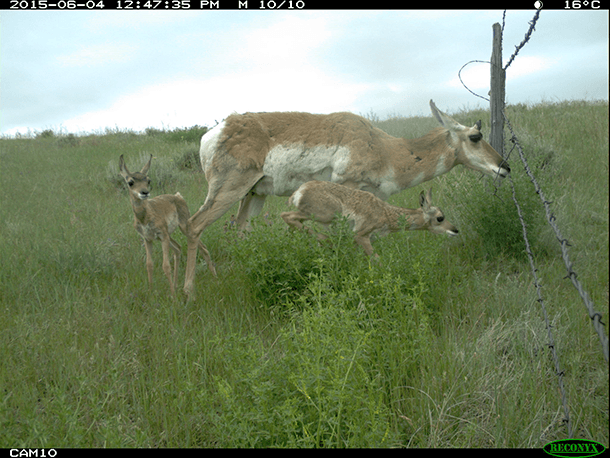

A camera mounted on a fence post captured a female pronghorn and her young looking for a way under a barbed-wire fence.

Pronghorn antelope are one of the fastest land animals on Earth, reaching speeds close to 60 mph. Once, their speed helped them outrun ancient predators, but today the pronghorn faces new challenges that its speed can’t overcome — barbed wire fences that block their ancient migration routes.

The pronghorn is not a true antelope, as classified by zoologists, but just about everyone calls the indigenous pronghorn of North America an antelope anyway. They are graceful animals, smaller than deer, found on sagebrush lands from northern parts of Mexico to the southern edge of Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada.

Some pronghorn populations make annual migrations of 250 miles or more, as they trek from their fawning grounds in the north to their winter range in the south and back again.

In Saskatchewan, ranchers traditionally use only two or three strands of barbed wire on the fences that mark their boundaries, and the antelope can easily slip under the fence. But there are many more fences in Alberta, Montana and elsewhere in the animals’ range that are typically built with five or even six strands of barbed wire. And that’s a problem, because for all their phenomenal speed, pronghorn do not like to jump.

“I think the idea of jumping over a fence is something that’s learned,” says Andrew Jakes, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Montana who has studied pronghorn antelope and their migrations for years. “They absolutely can jump and jump high. … It’s just that they’ve adapted to the tallest thing in their landscape being a sagebrush. So it’s not in their genes, if you will, to jump.”

In the antelope populations Jakes has studied — in Montana, Alberta and Saskatchewan — some migrate and some don’t. He says this two-pronged strategy has helped the species survive.

In their northern range, where the summers are fleeting and the winters harsh, the pronghorn need every advantage they can get. And that’s why the type of fencing the animals encounter on their migration is so critical.

When a herd comes to a barbed wire fence with the lowest wire set too close to the ground, they’re forced to go along the fence — often for a mile or more — until they find a place where they can squeeze under it. The barbed wire tears their hair, exposing them to the cold. And those extra miles spent searching for a crossing add up over the course of a long migration. More miles equals more energy expended, and less time for eating. On the northern prairies, that loss of valuable calories can be the difference between survival and starvation.

So Andrew Jakes has been looking for creative solutions to the fencing dilemma. “There are hundreds of thousands of fences out on the landscape, so it’s really useful to try to identify priority areas to start doing conservation work,” he says. “We wanted to do something that was cost effective, that had buy-in from the landowners and that would do the best by pronghorn.”

On the Matador Ranch in north-central Montana, Jakes, the Alberta Conservation Association and the Nature Conservancy of Montana are collaborating on an innovative fence modification project.

Their first step was to identify locations where pronghorn have historically crossed fences. Then they altered a 20-foot panel of fence adjacent to the crossing in one of three ways: by replacing the bottom strand with smooth wire, by fixing the bottom two strands together with plastic piping, or simply by clipping the bottom strands together. The idea is to see if the pronghorn could be taught to use the modified crossings.

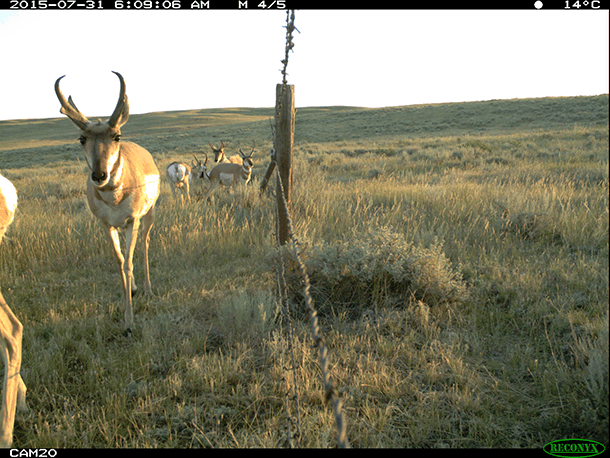

The team set up 16 observation sites, monitored by cameras attached to fence posts, to see how the pronghorn reacted to the changes. In the first few months of the Matador Ranch project, the cameras captured many images of pronghorn antelope. Some of the animals seemed to stare at the modified fence, unsure what to do, while others moved easily under it. The project is still in the data collection phase, so it’s too early to draw any conclusions about its success.

Knowledge of the migration routes is something that is learned and passed on from generation to generation, Jakes says. He’s confident that the fence modification project can help this ancient and hardy North American animal learn new ways to negotiate the obstacles in its path, as it makes the annual trek through the prairies it has inhabited for thousands of years.

This story is based on a report by Clay Scott that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.