How JFK made NASA his secret weapon in the fight for civil rights in America

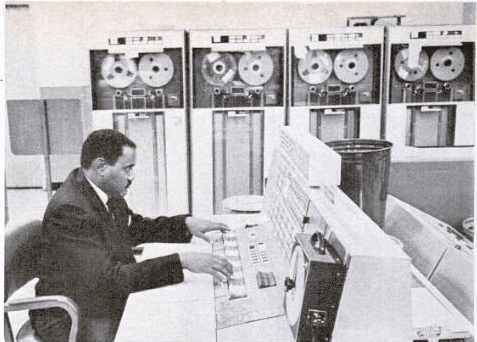

Clyde Foster processes telemetry at the Marshall Space Flight Center in 1965 in a photo that appeared in Ebony magazine. As a NASA employee, Foster was a leader in getting jobs and advancing engineering education for African Americans.

Most Americans know the name of the first black player in professional baseball — Jackie Robinson. But how about the first black professional in the US space program?

That was Julius Montgomery. He was part of a small cadre of African American mathematicians, engineers and technicians who helped power the space race — at a time when laws kept them from using the same toilet as their coworkers. (Later, he also integrated the Florida Institute of Technology.) These men were the vanguard of what became a government strategy to integrate the South.

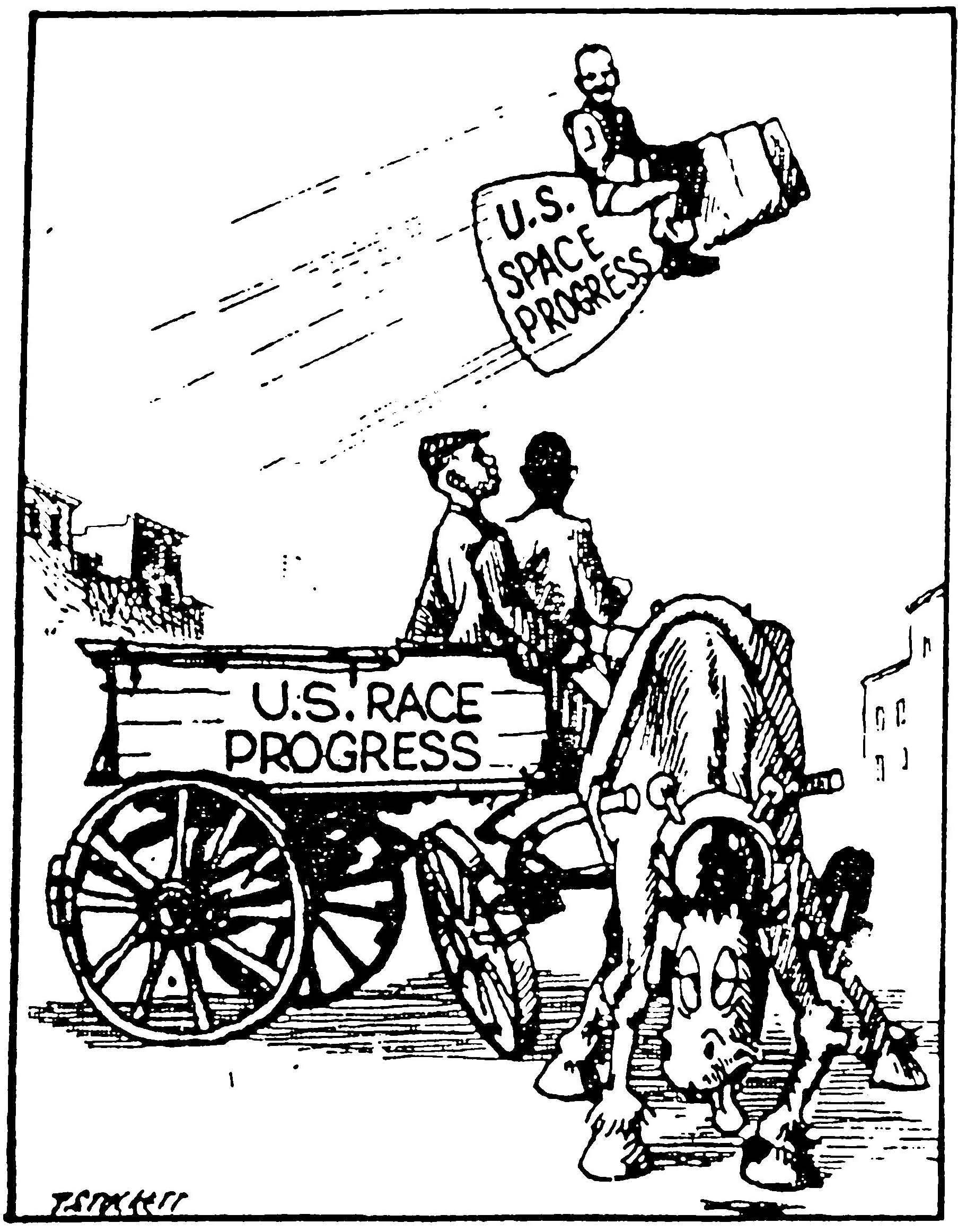

The idea came together because President John F. Kennedy had to deal with the Cold War, the space race and race relations simultaneously. In May 1961, Cosmonaut Yuri Gregarin became the first human in space, US-backed rebels were slaughtered at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, the Freedom Rides were met by bombings, rioting, mass arrests and the imposition of martial law, and President Kennedy committed the nation to put a man on the Moon before the end of the decade.

NASA and its contractors were creating 200,000 new jobs in the American South, from Alabama and Florida to Mississippi and Texas. And Kennedy and his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, saw jobs as a vehicle to achieving racial integration. Johnson thought southern poverty caused southern racism, and he believed that pouring money into the region could bring the South into the nation’s economic — and social — mainstream.

Kennedy placed Johnson at the heads of both his National Space Council and the President’s Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity, enabling the vice president to implement the strategy. NASA and its contractors were required to hire blacks, creating upper-level job opportunities that had never been available before to them, well before passage of the Civil Rights Act made equal employment opportunity the law of the land.

NASA created a contractors’ group in Alabama that used its money and influence to make sure African Americans got space jobs. The agency hired Charlie Smoot, called NASA’s “first Negro recruiter” in official histories, to travel the nation making the tough case to persuade black scientists and engineers to move into a South where they faced persecution and less freedom. NASA invited the presidents of the nation’s black colleges to Huntsville in 1963 and opened the agency’s college Co-Op program to blacks.

Then, through the early 1960s, the African American scientists, technicians and engineers continued the progress. When mathematician Clyde Foster couldn’t get into NASA’s whites-only advanced training program in Alabama, he convinced the agency to create a separate-but-equal training program for blacks.

Frank Crossley, the first African-American Ph.D. in metallurgical engineering, pushed his surprised superiors at Lockheed Missiles and Space to give him equal status with his peers after they had told him, “you are qualified to be a senior member, but because you are so advanced for a Negro, we thought you were content.” For his part, Julius Montgomery faced down Ku Klux Klansmen working at Cape Canaveral who refused to acknowledge him or shake his hand on his first day of work.

These men didn’t lead protests or sit-ins (even when given the opportunity.) They realized a different kind of civil rights victory — quietly breaking through color barriers in education, employment, and politics. They ended up embedded in what would become the New South — reviving and governing formerly defunct black towns, integrating southern colleges, earning Ph.Ds and good jobs in advanced fields and patenting important new inventions.

In May of 1961 after Alan Shepard’s historic Mercury mission, America’s leading black newspaper, the New York Amsterdam News, ran a front-page column that asked a question on the minds of millions of Americans. “If you are like me,” executive editor Jack Hicks wrote, “as soon as you finished thrilling to the flight of the United States’s first man into outer space, your next thought was, ‘I wonder if there were any Negroes who had anything to do with Commander Shepard’s flight?’”

The story of how African Americans contributed to US success in space is just making it into the history books. And so is the story of how the space race, the Cold War and civil rights came together to reshape the American South.