The ‘Texas miracle’ is fueling huge economic growth — and the climate change that may end it

The Houston Ship Channel stretches 52 miles from the Gulf of Mexico to the city of Houston. Sea levels have risen 2.2 feet over the last century at Galveston, the main barrier island protecting the Ship Channel from a big storm.

This report appeared on The World as a three-part series. You can listen to each of the audio segments below, or find the entire series here.

There’s not much beautiful about the Houston Ship Channel, but it's awe-inspiring in its own way: It’s the largest international port in the US and one of the busiest in the world.

The port is 52 miles long, hosts 7,000 ships a year, and is surrounded much of the way by warehouses, chemical and oil storage tanks, and construction cranes. It’s essentially one huge monument to the “Texas miracle,” the economic boom that’s delivered high profits and huge job growth even during the economic downturn.

But it’s also a symbol of Texas’ growing catch-22: Sites like the Ship Channel are fueling both the state’s economy and the effects of climate change — Texas is the nation’s top greenhouse gas polluter — bringing the state closer to a potential environmental and economic catastrophe.

And Texas’s leaders are largely in denial about the problem, saying they remain unconvinced by the overwhelming scientific consensus that human pollution is changing the climate.

(Listen to Part One)

(Listen to Part Two)

(Listen to Part Three)

That denial contributes to growing risks for Texas, starting with the Ship Channel. “I’m a little bit frustrated at the pace of progress,” says Houston's Democratic mayor, Annise Parker. She says she's trying to make the state government pay attention to the potential economic threat to the port.

The waterway is enormously vulnerable to big storms blowing in from the Gulf of Mexico, just 50 miles away. In 2001, Tropical Storm Allison caused an estimated $5 billion of damage around the state. And Allison was merely a preview of what might be ahead as climate change warms the world's oceans.

Experts say a big storm at just the wrong time could cause hundreds of billions of dollars in damage. There could also be global effects if shipping were shut down.

"This is real,” says Ray Newby, a coastal geologist at Texas’s General Land Office. "It could accelerate. And so we have to plan for it."

Three years of severe drought have left both reservoirs less than half full. Lake Buchanan’s water level is down roughly 30 feet, and you can drive along much of its vast, sandy bottom without fear of getting stuck — or even wet.

Millions of dollars in revenue and property value have been lost by homes and businesses around the reservoirs, not even considering the threat to the community from dwindling water supplies.

Higher temperatures mean even the huge amounts of rain that fell last summer just got sucked up by the soil, instead of replenishing water supplies.

“Even if rainfall stays the same, you’re going to have a lot more stress on water resources. Period,” says Victor Murphy of the National Weather Service in Fort Worth.

“Nobody ever anticipated that it would be this dry for this long,” says Kevin Kline, who owns a house on Lake Buchanan. “And unfortunately, there may or may not be an end in sight. ”

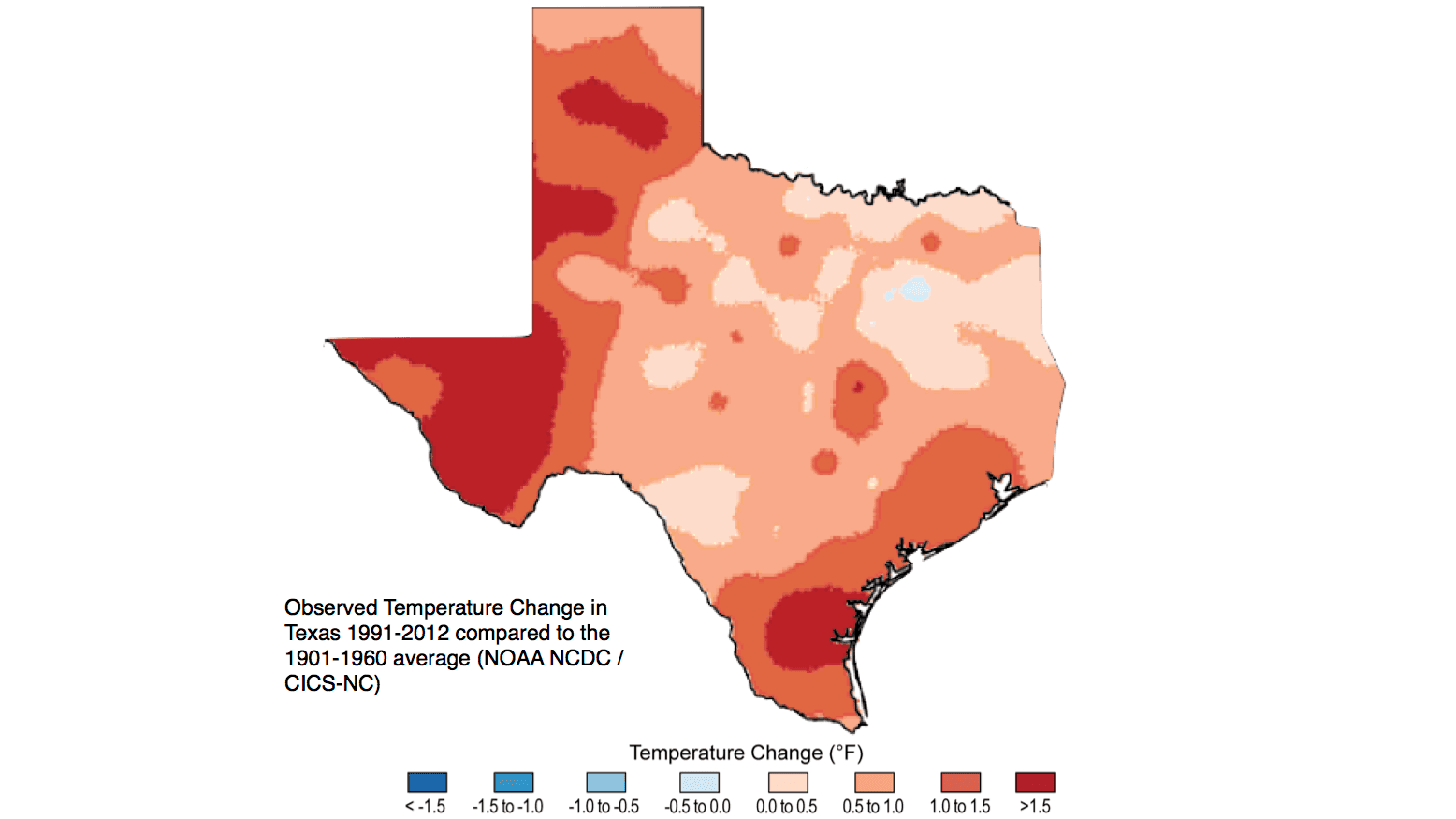

That’s because Texas is warming up. Over the last two decades, it’s become about one degree Fahrenheit hotter here on average.

In the Rio Grande Valley, the state’s fastest growing region, the average daytime high here could go from 97 degrees today to 106 by the end of the century, according to meteorologist Barry Goldsmith.

Goldsmith lives in Brownsville, a booming city in the valley on the Mexican border. But the rising temperatures mean the boom’s days could be numbered.

“142 percent population growth, the number one growth rate in Texas, happens to be one of the areas that would be one of the most impacted by longer-term lack of water,” Goldsmith says.

The state’s fast-growing industries are also at risk. At Ronald Gertson’s farm near the the Gulf of Mexico, the drought means an empty irrigation canal running alongside one of his fields.

It would normally be full of water from the same lakes that supply Austin, but there hasn’t been enough for rice farmers here since 2012.

Gertson was only able to plant a crop this year because he spent millions of dollars to drill wells below his land. It's a temporary fix at best; groundwater in the area is being depleted.

Gertson isn’t sure he believes humans are causing the temperature to rise. But no matter the cause, he knows what will happen if it continues.

“It could be devastating,” Gertson says. “Not just to our industry, but to every industry in this state, if we’re going into one of those really severe extended dry climates.”

Yet the state seems to be moving slowly, if at all, to address the potential effects of climate change.

Texas voters approved $2 billion for new water projects, but the agency in charge of spending the money doesn’t take a hotter and drier climate into account in its planning.

“The board doesn’t have an official position on climate change,” says Robert Mace, an administrator at the Texas Water Development Board. There’s also no state agency closely studying the possible effects of rising sea level on Gulf Coast region, with its oil infrastructure and six million residents.

The legislature’s answer probably won’t be much better: Neither Texas’ Republican-led legislature, nor its Republican governor, Rick Perry, accept the scientific consensus on climate change. The idea that humans are changing the climate is the subject of scorn and derision among Texas’s top politicians

That wasn’t always the case: In 2000, state regulators began working on a report on the impact of rising greenhouse gas emissions. A draft included warnings about bigger storms, higher summer temperatures, and their impacts on buildings, infrastructure and people.

But the report was crafted just as the politics of the issue were changing dramatically. George W. Bush said he took the issue seriously as Texas governor, but he began backtracking on climate promises and tamping down federal climate initiatives almost as soon as he took the presidency.

At the same time, a new fossil fuel boom was taking off in the US, especially in Texas. The 2000 report and its recommendations for cutting carbon emissions in Texas went nowhere. The argument for inaction then was the same as now: we just don’t know enough to take tough action to curb emissions.

“We need more science,” says Kathleen Hartnett White, who was a top Texas environmental official at the time. White says we still don’t know “the extent to which CO2 — manmade CO2 — is or is not dominating climate dynamics.”

White now focuses on climate and energy issues at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank. She says that even if climate scientists are right, and the US were to eliminate all CO2 emissions, “the impact on projected increases in temperature, because of other countries, would be like reducing it by .01 degree. I mean, not a meaningful reduction.”

Most climate activists disagree, saying the US needs to lead the world in cutting emissions. But it’s hard to do that without Texas. Along with being the biggest carbon polluter in the country, the state also has huge political influence in Washington and with other states.

“If Texas were more proactive in dealing with climate change, that would send a signal more broadly,” says Michael Levi, a senior fellow for energy and environment at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“The states have a direct impact on emissions,” Levi says. “The more states are doing to reduce emissions, the easier it is for the federal government to accomplish broader goals.”

But Levi’s doubtful that would happen unless the national conversation on climate started to move too, and that prospect has only gotten dimmer since this fall’s elections. For many, the November vote just locked in the status quo among Republicans.

“Climate change is associated with a liberal agenda that most Republicans are initially going to reject,” says Kip Averitt, a former Republican state senator in Texas.

His solution is to change the terms of the climate conversation. Averitt is now an advocate for lower-carbon energy like natural gas, solar and wind power. But when he talks about this with fellow conservatives, he has a strategy: Don’t mention “climate change.”

“When we talk about drought, that’s something everybody understands,” Averitt argues. “They see their water supplies drying out and they see the farmlands going to waste.”

“Oh, by the way,” he says, “that means we have to reduce greenhouse gases. We don’t mention that.”

But in some respects, says Larry Soward, a former state environmental regulator “we're already too late” to contain the risks to Texas. Soward was appointed by Governor Perry and counts him as a friend, but he’s become a fierce critic of Texas Republicans on climate change.

“If we don't start doing something today, we are going to have significant costs — in economic damage, property, lives, environmental damage — that could have been avoided to some extent,” Soward says.

Ronald Gertson, the rice farmer on the gulf, has a clear idea of how things might go as much of Texas warms up and dries out.

“We’re going to be wanting to send the people back north who came here over the last 20 years,” Gertson says. “And they’re going to be wanting to leave.”

This report is based on a series of radio pieces produced in partnership with The Texas Tribune.