This graphic designer makes ‘smell maps’ of cities around the world

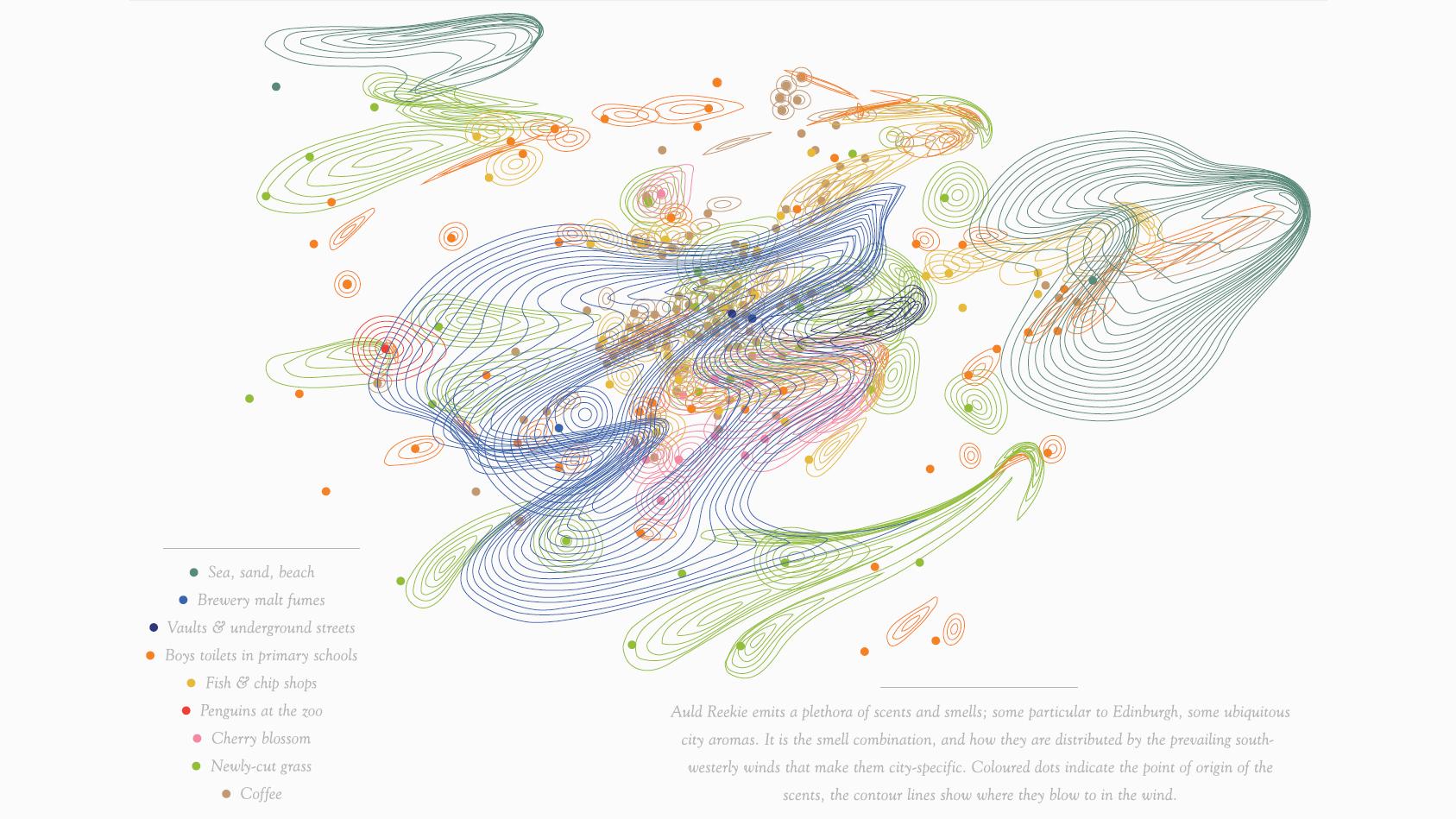

“Smells of Auld Reekie on a very breezy day in 2011” — Kate McLean’s smell map of Edinburgh.

What city can you smell?

Is that garlic bread? Or, is it garlic bread and bug spray? And sewage?

We’re walking through the North End, an Italian neighborhood in Boston. These may not be the kinds of things you’d notice on an average city tour, but this tour, it’s a smell walk. We’re just using our noses.

“It takes a lot of concentration to use your nose when you don’t normally use it in that way,” says Kate McLean, our guide. She laughs easily and wears a dark brown fedora. You can easily spot her in the crowd.

“I’m going to be really safety conscious here because one of the things that happens is you end up concentrating a lot on smell so if I say 'stop' or 'go' — go is when you should be crossing the road!”

McLean has conducted these smell walks in different parts of the world over the past several years. For her, they are sensory research trips. Today, she’s collecting data so she can map Boston by smell.

“What I’m very interested in is other people’s perception of a place by smell and then aggregating that to form smell maps,” she says. “They’re an attempt to make something visual that is ephemeral.”

McLean is a graphic designer and senior lecturer in graphic design at Canterbury Christ Church in England. She’s also a PhD Candidate at the Royal College of Art in London where she studies smell mapping. She’s already smell-mapped Edinburgh, Glasgow, Paris, Amsterdam, Milan, Newport, Rhode Island, and one particularly aromatic block in New York City. She has plans to work on smell mapping in Pamplona, Spain as well.

These maps are colorful interpretations of what a smell is doing in a particular place and how it moves. Take newly cut grass, for example. McLean smells it near a park, so on the map there’s a green dot in the park to represent the source of it.

Then, around the dot are flowing contour lines of the same color that show the strength or the range of that newly cut grass smell. The map legends include things like the ocean, beach roses, birds’ nests and fudge.

“We rarely have a common language for smell, which is another reason for putting it on a map and saying okay, it starts here,” McLean says. “It’s a suggestion about what you might smell when you’re here, but really it’s a call to go outside and actually smell for yourself.”

Ten of us weave through the aromas of the neighborhood. There’s a lot to smell on this block. I’m getting garlic and pavement and rubber tires.

“It smells really smoky in places; not bad, just smoky, like a cooking smoke, not a cigarette smoke. I’m hungry now,” says Lisa Johnson, a food blogger on the smell tour.

The other smellers include some of McLean’s graphic design students and me, a radio producer trying to capture smell in sound. Each of us has a sheet of paper with our mapped walk and room for notes – what do we smell as we walk and how strong is the odor – all data for McLean’s map.

We walk down an alley with window air conditioners humming. We take in the salt air of the waterfront, the smoke of cigarettes, a hit of strong cologne. It’s overwhelming to pay so much attention to it.

“I think we breathe something like 24,000 times a day, so there’s 24,000 opportunities for us to smell something every day, which when you think about it is insane,” says McLean.

She wanted to see whether smell really mattered to people, if it affected us in relation to memory and place. She started smelling places more closely, talking with local residents and smell experts, and leading smell walks.

One of the first smell maps McLean designed was of Paris.

“The smells there were cheese, wine, rain and Yve Saint Laurent perfume, because Parisian women take that away with them to remind themselves of Paris and where they come from,” McLean says.

Then Edinburgh.

“One of the smells was the boys’ toilets in primary school, another one was penguins at the zoo, and another one was the newly cut grass with a lot of the golf courses that actually are in the city," she says. "The domineering smell of Edinburgh is actually the brewery and the malt fumes from that. They can be detected way across the city.”

When Kate has exhibitions of her work, she recreates the smells from the maps in small bottles. So if you’re looking at her map of Glasgow, you could pick up a bottle to take in the oily sponges and soaking rusty nails – the smell of the subway. If you’re looking at the smells mapped in Newport, Rhode Island, you could take in the lobster bait by sniffing the bottle of a rotting skate.

“There’s something about saying, okay, you smell that but what do I smell? We have specific memories of places and smells that are very personal to us. They’re part of a picture we build up of a place. It has visual elements but it also has olfactory elements.”

We arrive at Faneuil Hall, a busy outdoor market in Boston lined with bars. Magicians make animal balloons; men in tiny food stalls sell roasted peanuts. And McLean catches a scent, one I wasn’t expecting.

“Whoa! I love that smell. This is the smell of sewers. I actually really like it!” she says. “Smells like that are proof that there’s life, there’s people. We’re creating smells, but then they’ll disappear into the environment. It’s evidence of life."

Update: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that we breathe 240,000 times per day. It's actually about 24,000 times.