40 years after the Arab oil embargo, America still loves its petroleum

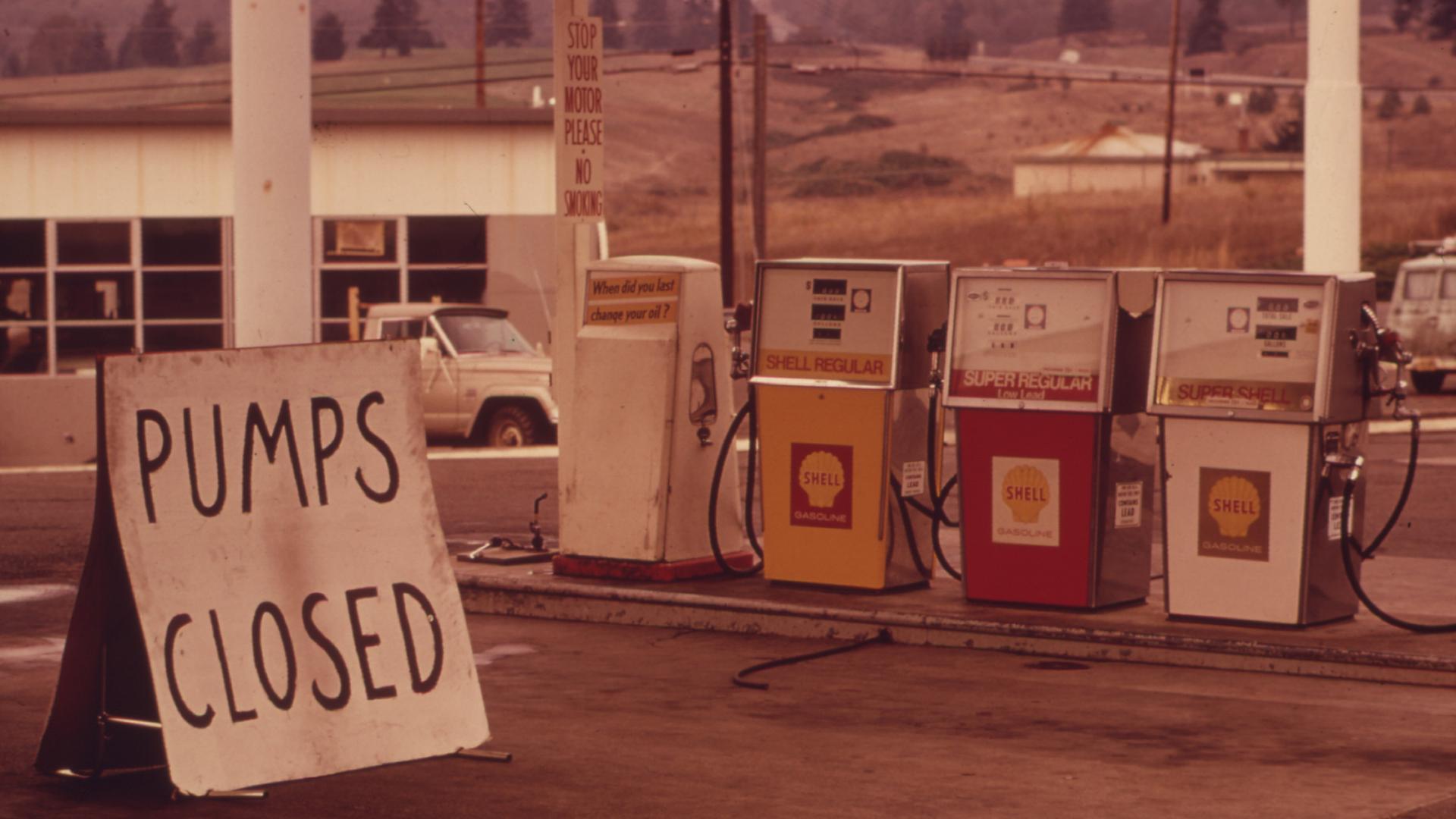

Gasoline shortages prompted by the Arab Oil Embargo hit this station near Interstate 5 in Oregon in October, 1973. The embargo roiled the US economy through the winter of 1973-74, before it was lifted on March 17, 1974.

Forty years ago this month, America heaved a big sigh of relief. The five-month long Arab oil embargo was finally over.

The previous fall, Arab oil countries had suddenly jacked up prices and cut supplies to the US and other western countries in retaliation for US support of Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

They called off the embargo on March 17, 1974, when the US agreed to negotiate with Syria and Israel. But the crisis rocked the heavily oil-dependent US economy, and it brought promises of big changes in US energy use.

So what became of those promises? Well first, let’s dial back a bit.

For those of us who lived through it, the oil embargo wasn’t just an inconvenience, it was an outrage. Cheap oil seemed an American birthright — never mind that we imported more than a third of it.

Everyone from country singers to President Richard Nixon vowed America would not stand idly by and let other countries determine our destiny. From now on, Nixon declared, American energy policy would be based on the truly American principle of independence.

For Nixon, the road to energy independence had four lanes. First, conserve — turn down our thermostats and build more efficient cars.

Second, create a strategic oil reserve, to guard against future shocks. Third, ramp up domestic production, by drilling in places like Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico. And fourth, develop alternatives to fossil fuels.

This last one struck a chord with a young engineer named Jefferson Tester. He had just gotten his doctorate from MIT and was eager to tackle “important problems” when the embargo hit.

“Many of us felt that was a career-changing event,” Tester says of the embargo. “It really put us on a very different path with respect to how we viewed our future as engineers and scientists.”

Tester decided to work on geothermal energy. It was challenging, it was socially useful, and there was funding, at least for a while.

“In the early period, it was sustained,” Tester says. “There was quite a bit of activity in almost every aspect of renewable energy development. But there wasn’t the political will to take a long-term view.”

That will was overwhelmed, says MIT energy historian Meg Jacobs, by the oil price collapse of the mid-1980s.

“All of that alternative energy research stops” at that point, Jacobs recalls. “So everyone who had been working on solar, or wind power, they just put all of their plans in the drawer.” And there they pretty much stayed for almost 20 years.

This was a problem, since new sources of energy typically take decades to develop. But who needed them when oil was so cheap?

By the late ‘80s, the US was on the energy version of a drinking binge. Over the next 15 years or so, we bought millions of gas-guzzling SUVs, we doubled our oil imports, and we fought two wars in oil-producing states in the Middle East.

But in the early 2000s, oil prices spiked again, driven at least in part by fears that the world was running out. And suddenly, energy independence was back on the agenda. President Barack Obama made it a plank in his 2012 re-election campaign.

At one rally in Oklahoma, Obama touted his administration’s record of opening up millions of acres of federal land and offshore tracts for gas and oil exploration.

“We are drilling all over the place,” Obama told the crowd. And, he said, that was paying off with a boom in domestic production.

Of course, the president went on to say drilling isn’t enough. He reiterated his call to keep improving efficiency and developing renewables — what he calls his “all of the above” energy strategy.

Forty years after the Arab oil embargo, the American energy picture is a lot less different than many people hoped it would be.

We get about 50 percent more of our energy from renewable sources now than we did back then, but it’s still less than 10 percent of the total. We use about 15 percent less oil per person, but that’s still five times the global average. And despite the current boom in domestic production, we import an even higher percentage than we did in 1974.

For Jefferson Tester, the geothermal engineer, that hardly sounds like progress.

“I guess I’ve become a little bit impatient with our lack of a true sense of urgency among the public right now to really move this along faster, with all of the signs out there — climate change issues, sustainability issues in general,” Tester says.

Of course, climate change and sustainability were not what motivated Richard Nixon to set out on the road to energy independence. But they’re very much on the minds of today’s young scientists and engineers.

Tester now teaches renewable energy at Cornell, and he says his students are feeling the same excitement he felt back in the 1970s.

“So if there was ever a good time for this country and other developed countries to reinvest in the future, now would be it,” he says. “Because they have a younger generation who wants to work on this, and there’s plenty of need.”

Forty years ago, our national challenge was how to reduce our reliance on unfriendly governments for our desperately needed oil. Now it’s how to wean ourselves from fossil fuels altogether.

Tester says that will take at least another 40 years — if, this time, we’re willing to stay the course.