‘The Story of Film’ took 6 years to make. You can see it in 15 hours.

Mark Cousins, during his six-year journey to create “The Story of Film,” shooting the skyline of Hong Kong with a statue of hometown hero and martial artist Bruce Lee in the foreground.

Most "histories of the movies" start the story with Thomas Edison and then head to D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, the studio system and beyond. With the possible mention of the Lumiere Brothers and a bit of French New Wave, it's usually an American story. Well, Irish film critic and extreme film enthusiast Mark Cousins wasn't happy with that version.

"There were big holes in movie history," Cousins says.

He should know. Cousins has found refuge in films — from just about everywhere — since his childhood in Belfast.

"It was a slightly nervy place. You know there was a war on, but when I went to the movie house, even before the movie started, I felt safe and could feel myself unwind and it just felt like getting onto a magic carpet and flying around the world."

Cousins spent his teens and 20s on the lookout for obscure films he'd read about in film quarterlies and journals.

"It was like dogged determination," says Cousins. "I would hear about some Ethiopian film from the 1960s. Sometimes it would take me eight years to actually see it."

He had an especially close long-distance relationship with Kim's Video Library in New York City. But the more films he saw, the more he realized something was missing from the many film histories he'd read.

"It seemed to me incredibly annoying that our general sense of what the great movies are, whether it's 'The Godfather,' 'Citizen Kane,' 'Taxi Driver,' 'The Searchers,'" says Cousins. "These are all great films but when we talk about the great movies we don't mention anything from Africa at all." Or from women, or Latin America. Cousins was frustrated. So he wrote his own history of the movies, "The Story of Film."

"I think 'The Story of Film' was made out of a degree of anger over the fact that the film history we have is far too narcissistic and far too self-regarding."

But then Cousins got the crazy idea of turning his 500-page tome into a documentary. And that's where the fun really started. Cousins spent the next six years traveling the globe, his film camera in his backpack. He'd catch up with famous film directors and film them in the comfort of their living room, no PR people, no talk of red carpets or movie stars.

But then Cousins got the crazy idea of turning his 500-page tome into a documentary. And that's where the fun really started. Cousins spent the next six years traveling the globe, his film camera in his backpack. He'd catch up with famous film directors and film them in the comfort of their living room, no PR people, no talk of red carpets or movie stars.

More importantly, he spent an enormous amount of time filming all the cities and towns where the great films of the world were actually made. And Cousins began to realize something.

"The more I traveled around the world, the more I filmed at dawn in Calcutta and the more I filmed in Paris in November with the ice on the streets, I began to realize that film is, among many things, the art of place. Cinema is brilliant at capturing the placeness of a place."

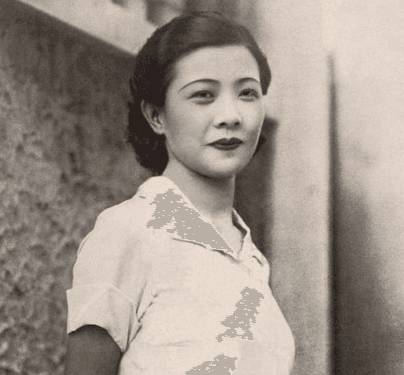

Cousins takes us to Shanghai to explore the thriving film scene there in the early 1930s. He films old movie sets and interviews older passersby about what they remember about those movies. Cousins is especially enchanted with a huge movie star from that era: Raun Lingyu, often called the Chinese Greta Garbo. Her films were gritty and realistic. One of them concerns a single mother who pays for her child's schooling by becoming a prostitute.

"People say that realistic acting began witih Marlon Brando in America. But Ruan expressed weariness, understated gestures, her body language. And this was in 1934," says Cousins.

Cousins loves American films too and spends plenty of time on them in "The Story of Film," but, at some point, he always pivots, as if to say, "But wait. Look what they were doing in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East."

He compares the experimentation going in the edgy American films of the 1970s like "Chinatown," "The Godfather" and "Mean Streets" with the so-called "third cinema" of Africa, where filmmakers were struggling to produce films that reflected independence from their colonizers.

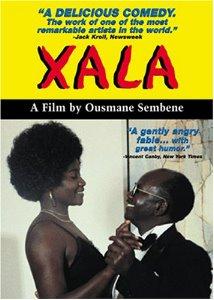

Cousins shows a scene from the 1975 film "Xala" by Senegalese director, Ousmane Sembene. It's a satire about a newly independent Senegal. In one scene, we see the newly liberated Senegalese smashing the symbols of their French overlords. In the next scene, the new Senegalese businessmen are acting just like their French colonizers, showing off their new briefcases and washing their cars with Evian water.

Cousins shows a scene from the 1975 film "Xala" by Senegalese director, Ousmane Sembene. It's a satire about a newly independent Senegal. In one scene, we see the newly liberated Senegalese smashing the symbols of their French overlords. In the next scene, the new Senegalese businessmen are acting just like their French colonizers, showing off their new briefcases and washing their cars with Evian water.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!