A US Marine’s Iraq War Diary

©The Diaries of Lt. Timothy McLaughlin USMC

In 2003, Lt. Tim McLaughlin led a Marine tank platoon as the invasion of Iraq began.

He kept a handwritten diary of those days; it forms the centerpiece of a new exhibition in New York.

"There are two books that I kept", Lt. Tim McLaughlin says. "One of them is an operations journal: it's grid coordinates, it's ammunition counts, it's platoon rosters. The other is a diary. Both of them are on very standard Marine Corps-issued green books. If anyone served in the Marine Corps they would recognize [them] instantly."

Pages from Lt McLaughlin's handwritten Iraq war diary are now on display at the Bronx Documentary Center in New York. They've been enlarged to poster-size, arranged in a grid across an entire wall.

On the cover of his diary he wrote the phrase: 'His horse was named death, and hell followed them'.

It might be from the Bible or Johnny Cash, he's not sure.

"We're trained to go to war. And that's what it is. It's hell and death and it's not fancy or romantic. I don't know where the quote came from though. Much like a lot of this stuff, I don't remember writing it although I remember the experiences."

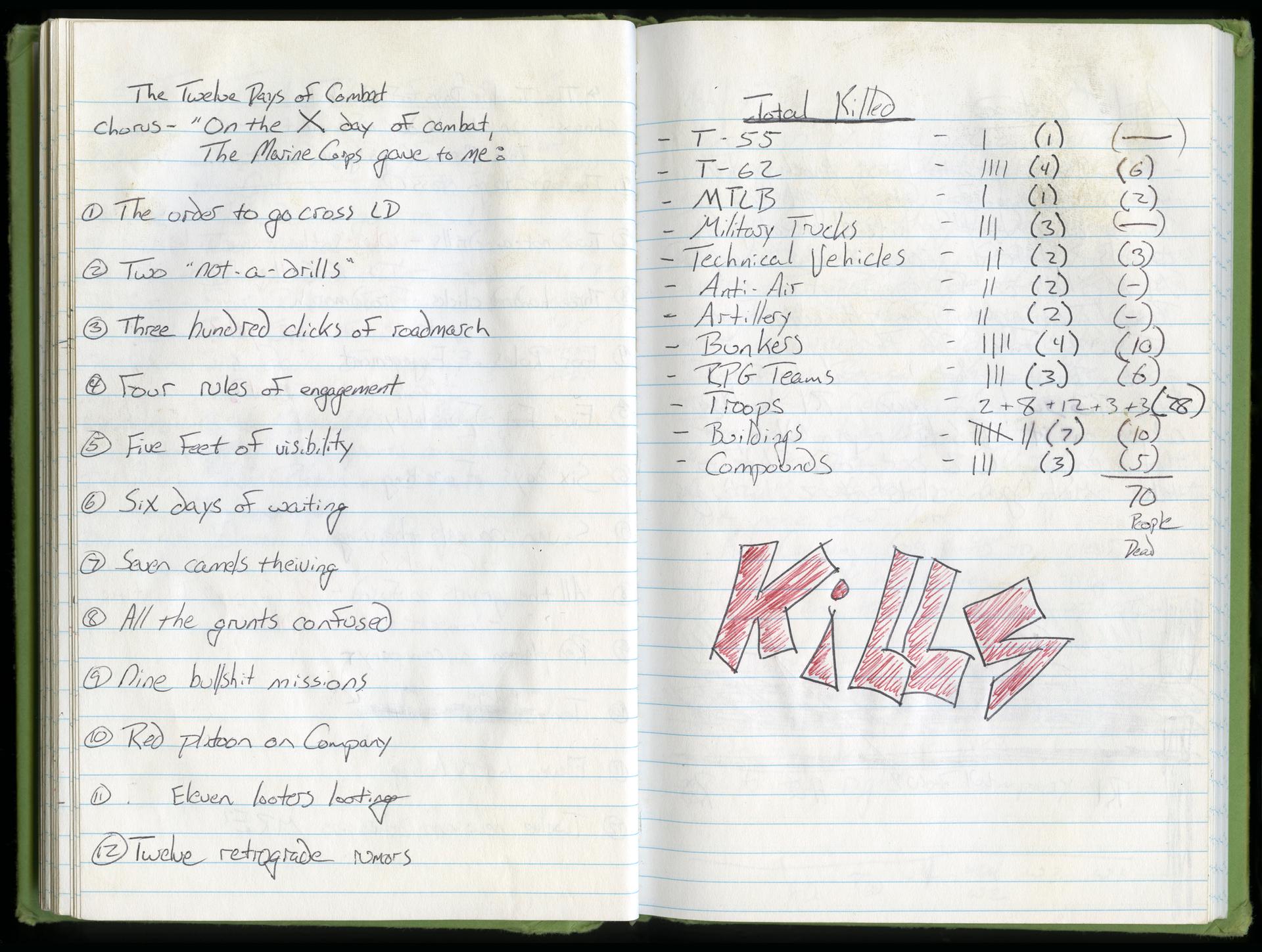

On one page of Lt. McLaughlin's diary there's a ledger, like something an accountant might write, except for what it's counting, and the word below, large and blocked out in red: 'KILLS'.

There's boredom too in these pages, daydreams: letters to his girlfriend, and one to Victoria's Secret. There are poetic summations of daily life atop a tank:

..two not-a-drills, three hundred clicks of road-march, four rules of engagement, five feet of visibility, six day of waiting, seven camels thieving..

The exhibition was put together by two journalists, the writer Peter Maass, and Gary Knight, a photographer. Both followed McLaughlin's unit, the Third Battalion Fourth Marines, during the invasion. Knight's images and excerpts of articles by Peter Maass sit alongside the war diary.

Knight says that for the general public, "these wars start on a certain day, they end on a certain day and that's it and they're done. But for the Iraqi civilians, for the guys who fought in the war, and for the small number of people who reported on it, it goes on forever."

Another member of Lt McLaughlin's platoon showed up on the day the exhibition opened, Gunnery Sergeant Nicholas Popaditch.

"He is probably one of three people who I respect in my life as educators", says McLaughlin. "He's a Silver Medal recipient, [had] multiple combat tours, took an RPG in the head, and is now blind. And [he] does extraordinary things for his community in San Diego, and just lucky to be here today."

Popaditch didn't know McLaughlin was writing a diary while they were in Iraq. Still, he says, "I like to think I probably have a pretty good idea of what's on all these pages here."

It's the first time the platoon sergeant and platoon commander have met up in almost a decade. Popaditch, who wears a black patch over his right eye, can still see a little out of his left. They crouch up close against a wall of photos, these ones snapshots that McLaughlin took during their tour together.

They show the tank platoon caught in time.

Lieutenant McLaughlin is now a lawyer in Boston. Gunnery Sergeant Popaditch has twice run for Congress. Like the journalists Peter Maass and Gary Knight, their personal experiences of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 are private and unknowable.

But this diary, these words, and these images: it feels like they get you pretty close.