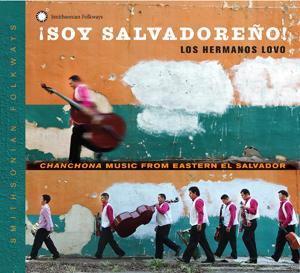

Salvadoran Chanchona Group Los Hermanos Lovo

“Soy Salvadoreno” by Los Hermanos Lovo

By Bruce Wallace

Thursday is Salvadoran Independence day. It commemorates the day in 1821 that Central America was freed from Spanish rule. Just in time comes the release of a new album by the group Los Hermanos Lovo. Los Hermanos play country music with roots in the rural, eastern region of El Salvador, although the group’s members themselves put down roots in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. more than a decade ago.

Their music has always been about partying, and that’s true on the new album “Soy Salvadoreno.” The song is an invitation to celebrate at the carnival of the singer’s homeland. Two violins sawing out the melody and the upright bass thumping around behind them are the essential ingredients of the “chanchona” style of music Los Hermanos play.

Dan Sheehy, the album’s producer and a specialist in Latin American music at the Smithsonian, says joy is another essential ingredient. “It’s about having a great time, it’s about smiling, it’s about laughing, it’s about getting people to dance, it’s about bringing community together to create a sense of community and just enjoy each other’s presence,” says Sheehy.

Chanchona music comes from eastern El Salvador, from the three, largely rural departments of Morazan, La Union, and San Miguel. The name “chanchona” literally means “sow,” — it’s a nickname for the heavyset upright bass that anchors chanchona groups. Many groups, Los Hermanos Lovo included, are made up of extended family, and the music is passed down from parents, aunts, and uncles.

The music’s roots probably stretch back to the early 20th century. In the ’50s and ’60s, radio spread Colombia’s infectious cumbia music throughout Latin America. Chanchona music picked up cumbia’s distinctive, two-step rhythm.

That chanchona music kept its joy through the 1980s and 90s in El Salvador is remarkable. A civil war engulfed the country, and it was most brutal in the east of the country — called the “Oriente.” Sheehy says that, in fact, chanchona music sometimes created a bridge between the two warring sides. “In eastern Oriente where the civil war was the fiercest, there were moments of extraordinary peace,” Sheehy says. “There were radio DJs in San Miguel—the capital of one of three provinces or departments that make up the eastern part of El Salvador–who told me a story about a dance celebration where a lot of people didn’t realize the presence of leftist guerillas and also people from the armed forces—from the right politically—and they intermingled, played and had a great time. And everybody loved the music of chanchona; that was a force that brought people together.”

The war forced many Salvadorans to flee the country. A lot of them came to the United States, and carried chanchona with them. Among these refugees were members of Los Hermanos Lovo, who settled in northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. Trini Lovo, the group’s leader and one of its violinists, came in the late 90s. Lovo says the music is a way of reuniting people, and of celebrating. He was working two other jobs when he got here, but still found time to play music at restaurants around Washington.

A lot of the songs on the album “Soy Salvadoreno” look back at El Salvador with a homesick eye. “Las tres fronteras,” one of the two songs that Trini Lovo wrote for the album, says of El Salvador: “Love and pain are always in my country.” “It tells of how you leave your family behind.” Lovo explains. “When you depart, you shed tears, because you leave your children, your wife. It says ‘sorrows’ because we leave sadness, and ‘love’ because what we are going to do here is work, so that our family might live a better life.”

Sheehy says that chanchona music has become a source of regional pride in El Salvador, helped by a two month-long battle-of-the-chanchona-bands festival that a radio station puts on every fall. “Chanchona is a flag of identity–of musical identity, of regional identity,” Sheehy says. “And this is why folks down in El Salvador who organize the annual festival and all the events building up to that, they realize that this was a musical flag, and they realize that with all the globalization, they were going to lose what was really theirs, what defined them.”

Not bad for lovers of a type of music that takes its name from a pig.