What Constitues a Famine?

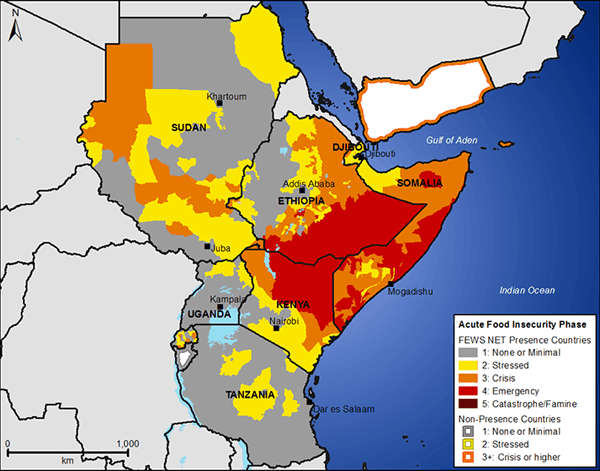

Estimated food security conditions, 3rd Quarter 2011 (July-September 2011)(Graphic courtesy: Fews Net)

By Rhitu Chatterjee

If you look up the word “famine” in your dictionary, you will find it defined as ‘extreme hunger,’ or ‘starvation.’ That seems to describe what people are experiencing in East Africa, and it is a word some recent news reports have used.

But if you ask some scientists working on food security issues, you will find them steering clear of the word.

“There’s been an enormous shift away from using ‘famine’ as a label,” said NASA’s Molly Brown, who works as part of the US government’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network, or FEWSNET.

FEWSNET forecasts food shortages in different parts of the world.

Brown said that in decades past, governments and aid organizations often used the word famine to describe food emergencies, but they are less likely to do so today. In fact, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network has never declared a famine since its launch in the mid-1980s.

There are several reasons why experts avoid the word famine.

For one, it can sometimes make national governments defensive. Politicians look bad if a famine has been declared in their country, and they may deny the problem and refuse help to save face.

Also, declaring a famine can have unintended effects on local food markets.

“People who have available food for sale might say, ‘Oh, maybe I’ll wait another month or two because the prices are all going to go up,'” Brown said. That can mean even less food is available to those who need it.

Brown said using the famine label can be a good thing because it spurs the international community to act, but using the label too readily can backfire.

“If in 2012 they have another drought, or the drought continues, what are they going to do?” she asked. “If you use that trump card, you can’t take it back, and you can’t reuse it.”

So if “famine” is too weighty, emotive, and political a word to use — at least for now — how does one describe situations like the current one in East Africa?

For scientists and food aid experts, the answer is something called the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, which is a standardized scale that enables experts to rate food security from one to five, using a host of factors.

Nicholas Haan, cofounder and executive director of the IPC, explained that those factors include “rainfall, conflict, crop production, livestock conditions, nutrition,” and other measures.

A rating of one means an abundance of food. Five is the worst-case scenario — a famine.

Right now, in East Africa, the situation is phase four, or a food security emergency.

“In this particular case, it hasn’t yet reached famine levels,” said Camilla Knox-Pebbles of the aid group Oxfam, “although there are some indications that in some places we are very close to that given the high malnutrition levels.”

And that means the situation in parts of East Africa could officially be designated a famine soon if, experts say, the international community does not help now.