Kyrgyzstan’s walnut forests dwindle with increased cattle farming, climate change

On a crisp October afternoon, Bakhadir Fazilov approached a tall walnut tree, wrapped his legs and arms around the trunk and began climbing toward the top — more than 40 feet above ground.

At the top of the tree, Fazilov nimbly stepped out onto a flimsy branch and began shaking the limbs until the walnuts came crashing down to the ground.

Kyrgyzstan is home to the largest natural walnut forest on Earth. It’s a unique ecosystem with more than 30,000 acres that rises above the bustling town of Arslanbob, not far from the Uzbekistan border. But climate change and increased cattle farming have created intense pressure on the walnut forest.

Every fall, locals like Fazilov camp out in the ancient, shadowy walnut forest in southwestern Kyrgyzstan for up to two months. In a good year, harvesters can pick literally a ton of nuts, and buyers come from as far away as Turkey and Russia to purchase the crop. But this year, the harvest was so poor that few locals even bothered to lug their tents up into the mountains to pick the walnuts.

“Last summer, the weather was really hot, so all the nuts fell off,” Fazilov said.

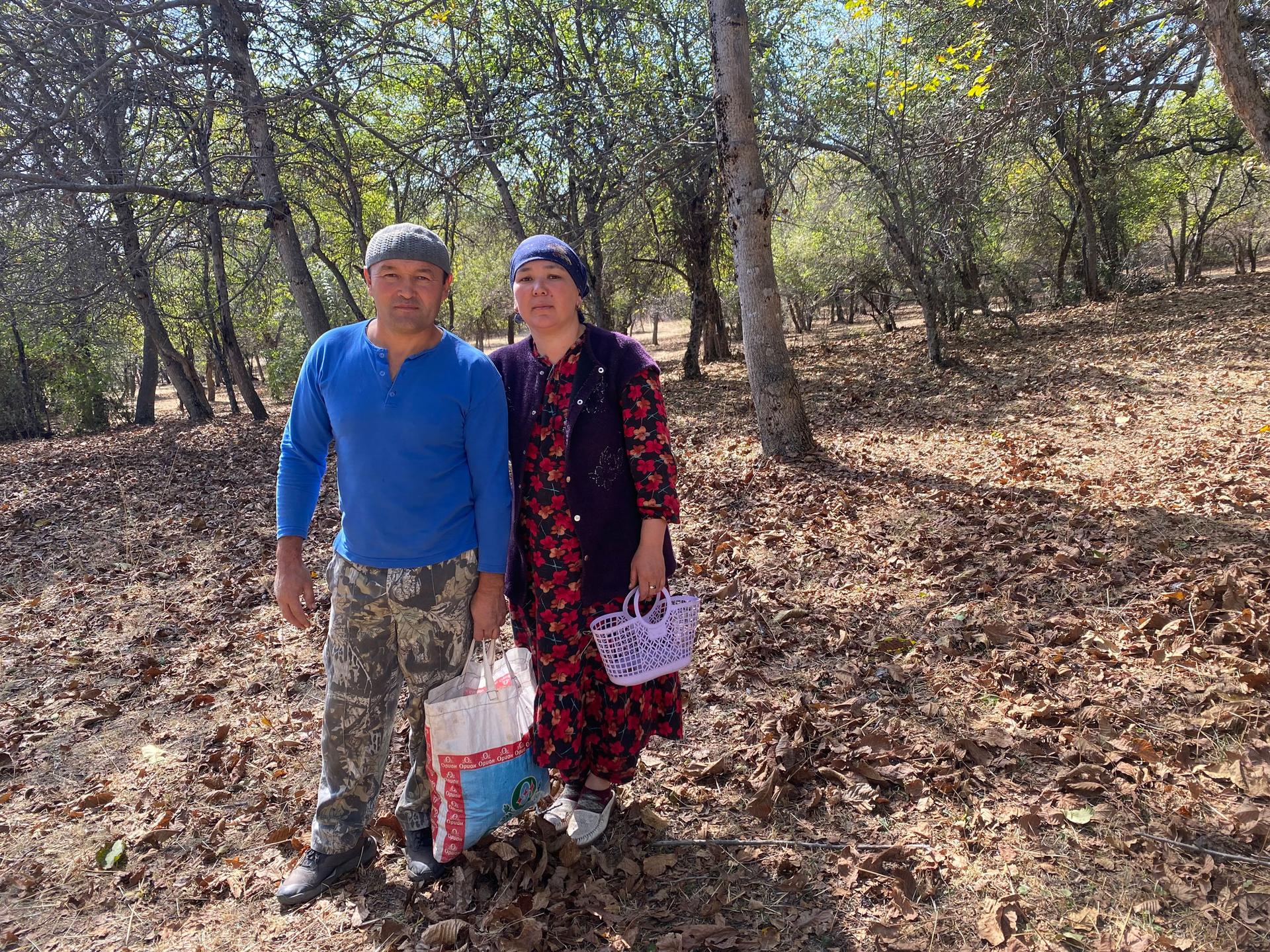

The walnut forest where Fazilov sets up camp with his wife and four children each fall is government land. Fazilov rents about 10 acres for about $80. In a good year, he can earn more than $1,200 for the season. But this year, he might only make of half that.

Livestock present an even more pressing challenge to the walnut forests than climate change.

Many Kyrgyz make a living herding cows and sheep that graze on pastures in the nearby mountains that rise above the walnut trees. Most of those pastures also belong to the government, but authorities don’t put many limits on livestock grazing.

In the region surrounding the walnut forest, livestock numbers have been increasing by 3% to 4% annually, and the pastures are getting depleted. Now, herders let animals roam the walnut forests in search of food.

The thick forest also provides a shade for animals and herders during the sweltering summer months. Cows eat the little walnut saplings, which means there’s no new growth. And horses roaming through the forests also eat the bark, which kills the old trees.

“Just look at all the wounds on this tree,” Fazilov said, pointing at the yellow wood where a horse had stripped the bark. “We can’t pick a good harvest because of this [damage].”

Fazilov said he would like to put up fencing in this stretch of forest that he rents to keep the animals out, but he said that he can’t afford it.

In rural Kyrgyzstan, many have few economic opportunities besides migrating to Russia or staying at home and working the land — which often means herding animals.

Environmental workers there say that many Kyrgyz are distrustful of banks, so people invest what savings they have in animals. The idea is that selling animals for meat is a better investment than the meager interest earned in a savings account.

But herding animals has led to severe environmental problems, such as increasing desertification and a loss of plant diversity.

On a hill in the pastureland high above the walnut forest, livestock have eaten all the plant life down to the dirt. The only vegetation that remains is bits of dry chaff and grass lying on the ground above black dust.

“This hill is naked, the animals ate everything,” said Nurgazy Nurbaev, a manager at the Kyrgyz environmental organization CAMP Alatoo, as he gazed out at the desiccated pasture. “There’s 2 ½ times more animals grazing here than the pasture can support,” Nurbaev said.

At the top of the hill, CAMP Alatoo has installed two big metal cages secured with padlocks. Inside there’s grass and shrubs growing.

“This is what the pasture would look like if there were no animals,” Nurbaev said, gesturing toward the cages.

CAMP Alatoo’s researchers collect data in these cages to gauge how much grazing the land can actually support. They make recommendations to herders about how to better manage the land. But CAMP Alatoo’s project manager, Jyrgal Kozhomberdiev, said that not enough herders are following their advice.

“Many people are just continuing [on], [with] business as usual,” Kozhomberdiev said.

Kozhomberdiev hopes that technology can be part of the solution. CAMP Alatoo helped to digitize different pasture management programs around the country. Local pasture committees can use this information to figure out where to move herds to less congested pastures and gauge their environmental impact.

And this year, CAMP Alatoo helped develop a new smartphone app called Pasture Monitoring that herders and researchers can use to document the changing environment.

Available in Kyrgyz, Russian and English, the app requires users to take a picture of the landscape they see and then select from checklists that describe characteristics, such as plant species and soil quality. Users also tag their location and can choose to link the information they collect to a server that scientists can access.

“This type of information was not collected since the Soviet Union collapsed, due to a lack of funding, so we think that this mobile app can facilitate the process [of data collection],” Kozhomberdiev said.

Scientific research on Kyrgyzstan’s pastureland has been virtually nonexistent for several decades. It’s the herders who have some of the most in-depth knowledge about how the changing climate is affecting local ecosystems. While they have exacerbated recent environmental problems, they can now be a key part of the solution.

There are actually two ways to harvest a walnut in Kyrgyzstan — some may wait until a strong storm blows through and knocks the nuts to the ground. But many locals hope to continue to camp out in the walnut forest, climbing up the trees to shake the nuts free each fall.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?