Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there’s been a scramble for workers across the United States. With fewer employees available, service in the hospitality sector has slowed down, creating a crunch at restaurant kitchens, hotels, factories and even in high-tech.

A major factor for the shortfall has been a lack of foreign workers. The availability of US-born labor has also taken a nosedive, making finding workers a huge challenge.

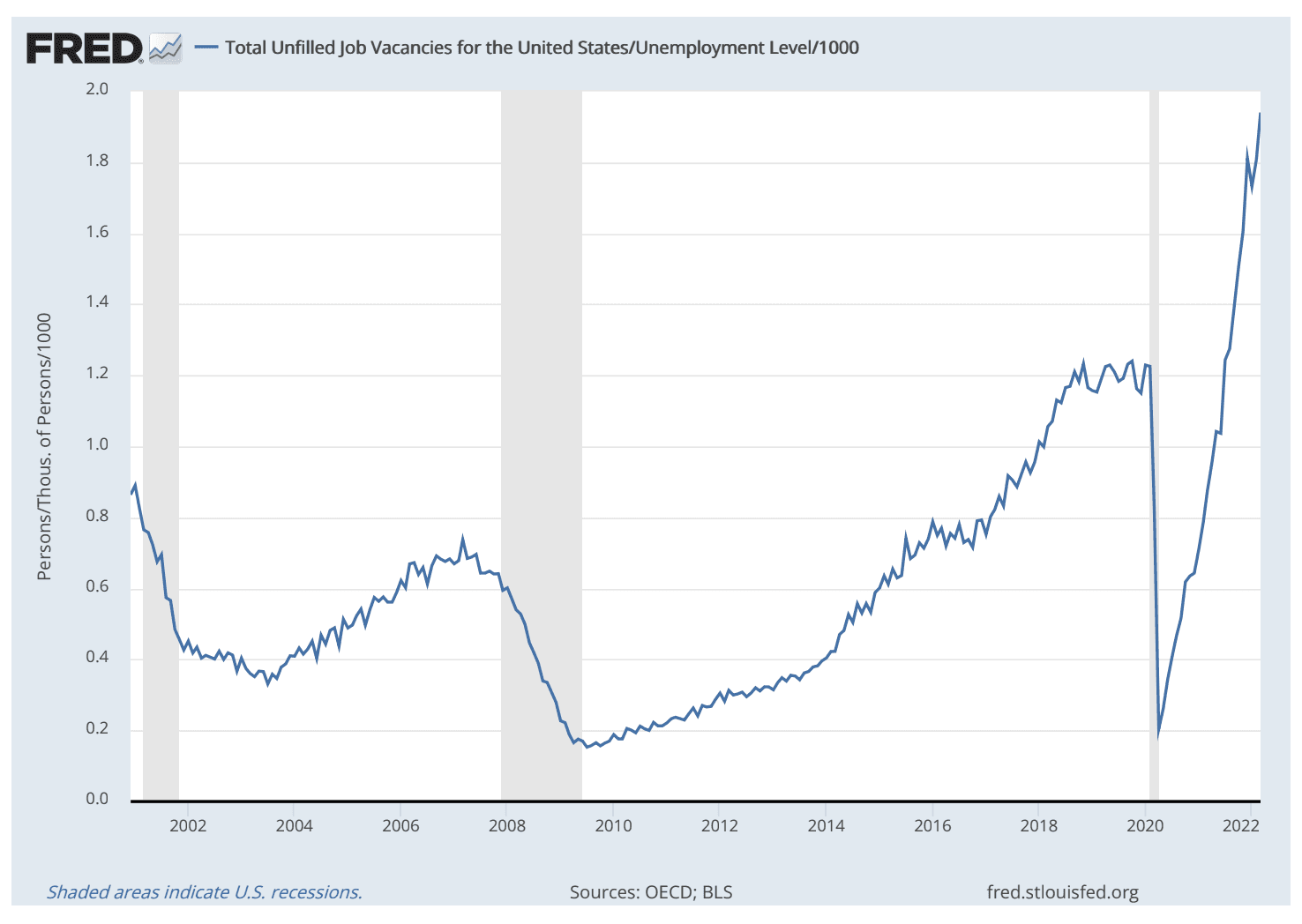

According to a chart compiled by the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), there have been consistent ups and downs over the years in the number of unfilled job vacancies for each unemployed worker. At some points there are more jobs than workers and vice versa.

But the trend shifts drastically during the years of the pandemic.

“It’s just completely unprecedented. It’s spectacular really,” said Brian Kovak, a labor economist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, after poring over more than a half century of data.

“Now the labor market is much tighter. And that means there are nearly twice as many job openings as there are unemployed workers searching for jobs.”

“Now the labor market is much tighter,” he said. “And that means there are nearly twice as many job openings as there are unemployed workers searching for jobs.”

It’s something that economists call “labor market tightness.”

“It’s extremely difficult,” said Christopher Bender, the CFO of Stoneacre Hospitality Group, which consists of two restaurants and a soon-to-be-opened bed and breakfast in Newport, Rhode Island.

Bender said that during the height of the pandemic, like many restaurants, they had to find creative ways to make do with a smaller staff.

“Sometimes that means we can only activate certain areas of the restaurant at a time,” he said.

At his Stoneacre Garden location, a restaurant serving Asian-inspired cuisine near Newport’s waterfront, the empty tables meant less money for Bender and his employees — and longer waits for his customers.

“There has been a boom of retirement during the pandemic. And there has been a much slower inflow of immigrants in the US.”

Economist Giovanni Peri, at the University of California, Davis, summarized how this crunch developed over the past two years. “There has been less willingness of workers to accept some of the job conditions,” he said. “There has been a boom of retirement during the pandemic. And there has been a much slower inflow of immigrants in the US.”

Those slower inflows have been of people on green cards and work visas — as well as undocumented workers, who are harder to track. And their absence has been acutely felt across certain industries.

Peri says that about 30% of employees in the hospitality, retail and food industries are immigrants.

And like Peri’s estimate, about 30% of the staff at the Stoneacre restaurants in Newport is also from overseas, mostly from Eastern Europe.

Like the restuarant’s 20-year-old Vili Pendicheva from Bulgaria — “I got here on a J-1 visa that they provide to students.”

The J-1 visa allows students like Pendicheva to work in the US through the summer, then travel for a month after.

“The working visa is three months and then you get a one month bonus,” she said. A bonus month to travel and explore.

Restaurants and hotels in popular summer tourist areas — from North Carolina’s Outer Banks to Cape Cod to Branson, Missouri — all rely heavily on workers with temporary visas, both the J-1 and what’s known as the H-2B. Small business owners say year after year, they can’t hire enough Americans to fill the positions.

Critics say that businesses should offer to pay higher salaries. But, business owners counter that, even if they do, there just aren’t enough locals near their towns that swell during tourist season.

Christopher Bender at Stoneacre said that he pays above-average wages to his employees and has offered them three days off each week. But without his overseas staff working during the summer months, he said that “it would be virtually impossible, or we would most likely have to move to a different [smaller] location.”

But Bender said he’s seeing closer-to-normal staffing levels with his international workers, and the more general data also echoes those numbers.

“What we’ve seen in the last six months is that the immigrant labor force is rapidly catching up to the pre-pandemic trend,” said economist Brian Kovak from Carnegie Mellon.

But he added that “the US-born labor force remains about 4 million workers below that pre-pandemic trend.”

And with even fewer American workers, that can translate into intense competition to hire workers coming from abroad.

Bender said that in Newport, they’re trying to work with what they have.

“Fortunately, the restaurant community in Newport is pretty tight-knit. So, we do work with a couple of the other local restaurants and we try to share back and forth as we find many of the students coming, especially on the J-1 visas.”

That includes people like Vili Pendicheva, who is currently working two jobs bussing tables at two different restaurants. But she said she’s not complaining about the longer days, because it’s a much more lucrative summer gig than what she’d find back home in Bulgaria.

“On a good day here when it’s really busy, if I earn, let’s say, like, I don’t know, $300,” Pendicheva said, “I’ll earn that there [in Bulgaria] for the week.”

Related: Despite flurry of efforts to recruit immigrants with medical experience, many remain sidelined