When Jean, a physician from Democratic Republic of Congo, sought asylum in the US for his human rights work, he planned to continue working here as a doctor. His full name isn’t being used since his asylum claim is pending.

Jean soon discovered that it would be nearly impossible to return to his profession. He said the licensing exam alone was prohibitively expensive — and that’s even before he confronted the bigger hurdles of transferring credits and landing a medical residency.

Instead, he settled for working as a certified nursing assistant (CNA) — bathing, feeding and dressing hospitalized patients.

“You need to humble yourself,” he said. “You know many things, but just humble yourself to do what you can do.”

Jean’s story is not a new one. Immigrants to the US, in all sorts of professions, face barriers to getting credentialed. And when it comes to caring for patients, there are good reasons for making sure doctors are qualified. But some health care experts say there’s also good reason to help foreign-trained medical professionals continue their careers in the US.

Susan Bell, a medical sociologist at Drexel University, agrees with the latter.

“We desperately need in the United States a more diverse health care system [with] providers to be able to provide care to an increasingly diverse patient population.”

“We desperately need in the United States a more diverse health care system [with] providers to be able to provide care to an increasingly diverse patient population,” Bell said.

There’s also a shortage of health care workers in the US, which became starkly evident as the pandemic strained medical systems across the country.

As states scrambled to recruit more health care workers, some took new interest in the estimated 270,000 immigrants in the US with medical backgrounds who were unemployed or working below their skill level at the start of the pandemic, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

Related: Echoing WWII rescue efforts, ethnic Russian researchers in the US support Ukrainian scholars

New Jersey stepped out ahead of the rest in early 2020, becoming the first state in the country to offer temporary medical licenses to foreign-trained physicians.

But only a handful of licenses were granted, and the program was temporary.

For many immigrants with health care skills, despite a flurry of efforts to loosen requirements for foreign-trained medical professionals during the pandemic, the only realistic path back into their field is to start all over again. Often, that means taking a certified nursing assistant course, like the one taught by Aimee Biba at Portland Adult Education in Maine, which is part of the public schools system.

Biba was a nurse anesthetist in DR Congo before moving to the US in 2011, and said she was not able to get credit for previous work or educational experience. So, she went back to nursing school for four years while continuing to work full time as a housekeeper to support her family.

Sally Sutton, program coordinator at the New Mainers Resource Center, a workforce integration program at Portland Adult Education, said Biba’s experience is fairly common.

“It’s a real challenge to both figure out how to support yourself and your family, and figure out how to get back to work towards your career and all of the expenses that that takes,” Sutton said.

For physicians, Sutton said it’s even more challenging because they must complete a residency program — and compete against recent US medical school graduates for a limited number of spots.

The result, she said, is that almost none of the foreign doctors she’s worked with are able to return to their profession.

“We don’t have systems here that know how to take advantage of people who are here as refugees and asylum-seekers.”

“We don’t have systems here that know how to take advantage of people who are here as refugees and asylum-seekers,” she said.

Washington state tried to tackle the residency problem with a new law that allows foreign medical graduates to obtain temporary licenses without completing a residency.

But that two-year license can only be renewed once.

Related: Colorado joins handful of states that give financial aid to undocumented college students

“I mean, I’ve talked to some physicians [in Maine] who are ready to move to Washington state,” Sutton said. “And again, you know, that’s not even quite the right answer yet.”

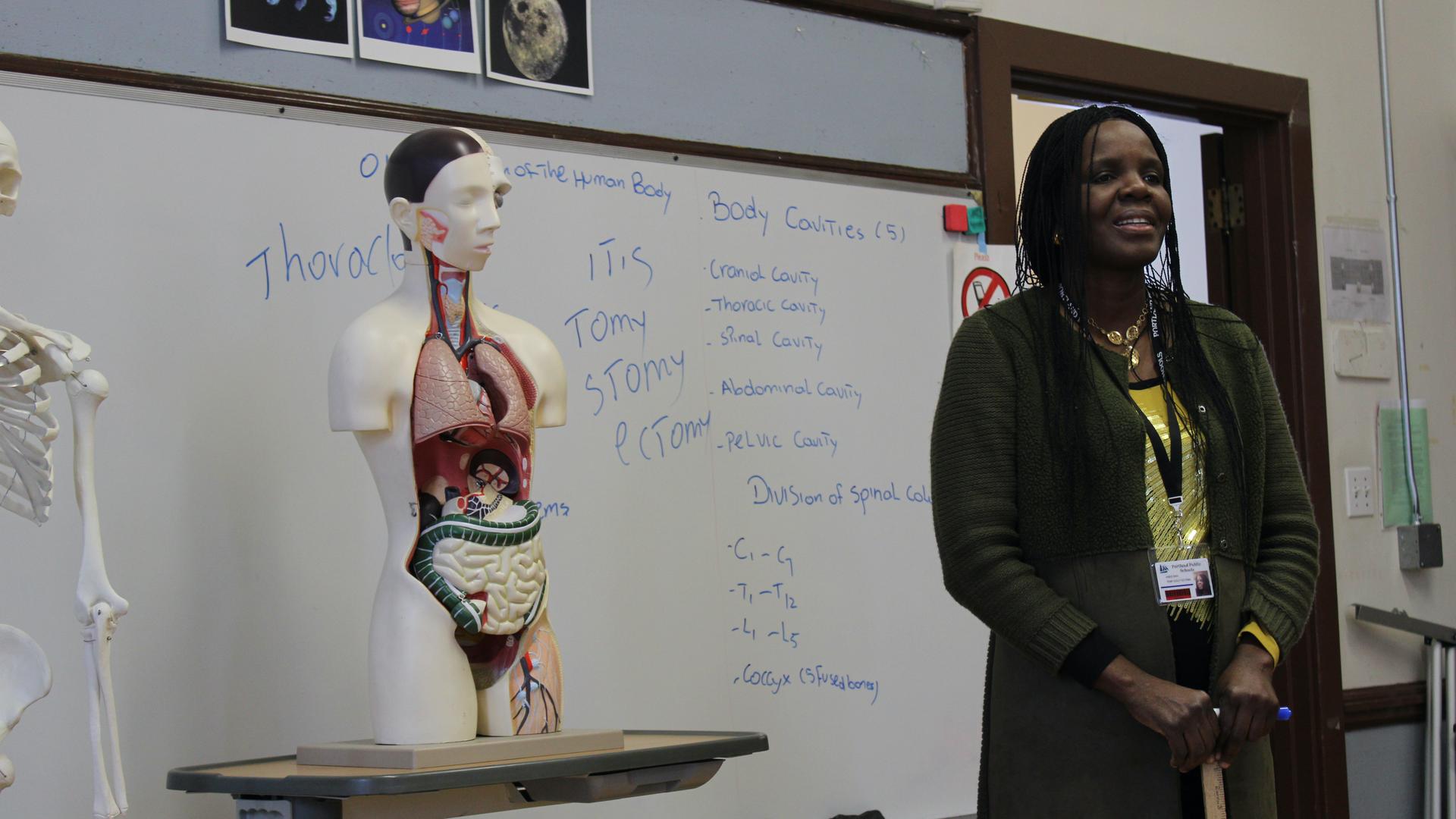

In the face of these barriers, CNA instructor Biba said that she feels a responsibility to help her students, many of whom, like her, were medical professionals in their home countries.

“This is what I [tell] my students, you know, you just need discipline,” Biba said. “Know what [you are] doing, knowing your goal.”

But even as she encourages her students to stay determined, Biba said the many barriers to certification are leading to a lot of wasted talent.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?