As India becomes the world’s most populous nation, engaging men in family planning ‘will be a game changer’

At the district women’s hospital in Meerut, about 50 miles from India’s capital New Delhi, 32-year-old Moni Devi cradled her pregnant belly as she sat in a metal chair waiting for a routine checkup.

“This pregnancy was unplanned,” Devi said. She and her husband already have two children — a girl and a boy. They didn’t want any more, she said, because their family’s financial situation is unstable. Devi’s husband works in the private sector where job security isn’t guaranteed. “I considered an abortion, but my in-laws were against it, so we’re going to keep the baby,” she said.

She’s not taking any more chances though. Soon after her delivery, she said she will undergo a tubectomy, or female sterilization, to prevent any unwanted pregnancies in the future.

Women across India echo Devi’s rationale for wanting a small family. Government data shows India’s total fertility rate, which is the average number of children per woman, has dropped to two (just below replacement rate, the rate at which a population exactly replaces itself without migration). In the 1950s, it was around six, suggesting that India’s population is stabilizing.

On Nov. 15, the world’s total population crossed the 8 billion mark. India, with a population of about 1.4 billion, is the second-most populous nation in the world. The United Nations projects that next year, India will surpass China and claim the title of the world’s most populous country. But demographers in India aren’t panicking, because India’s population growth has actually been slowing down for many decades.

“The population explosion age has gone now and we are in a reasonable growth period, it is not a very alarming growth anymore,” said K. S. James, director of the International Institute of Population Sciences in Mumbai.

The credit goes to a decadesold, government-run family planning program which has successfully reduced India’s fertility rate through awareness programs and increased access to contraceptives, and without coercive measures like China’s one-child policy.

Family planning burden falls on women

In rural areas across India, female health workers like Somvati Asar spread awareness about contraception in their communities. Every week, Asar goes door-to-door in a handful of villages under her care in western Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. She advises women to maintain a minimum three-year-gap between successive births and distributes condoms and contraceptives. In her four years on the job, she said she has convinced dozens of women to undergo contraceptive procedures like IUD insertion and female sterilization. But she has only been able to convince one man so far for a vasectomy, she said.

“Men think getting a vasectomy is an attack on their self-respect,” Asar said. Many refuse to get it done despite governmental financial incentives to those who opt for it. Another health worker said that men flatly refuse to talk to her about family planning.

Alok Vajpeyi, a public health researcher at the New Delhi-based Population Foundation of India, said there are a lot of myths and misconceptions about male sterilization.

“Men think that they will lose their virility or they won’t be able to enjoy sex after going through vasectomy,” Vajpeyi said, and as a result, “the onus of family planning rests on women — the entire burden falls on women.”

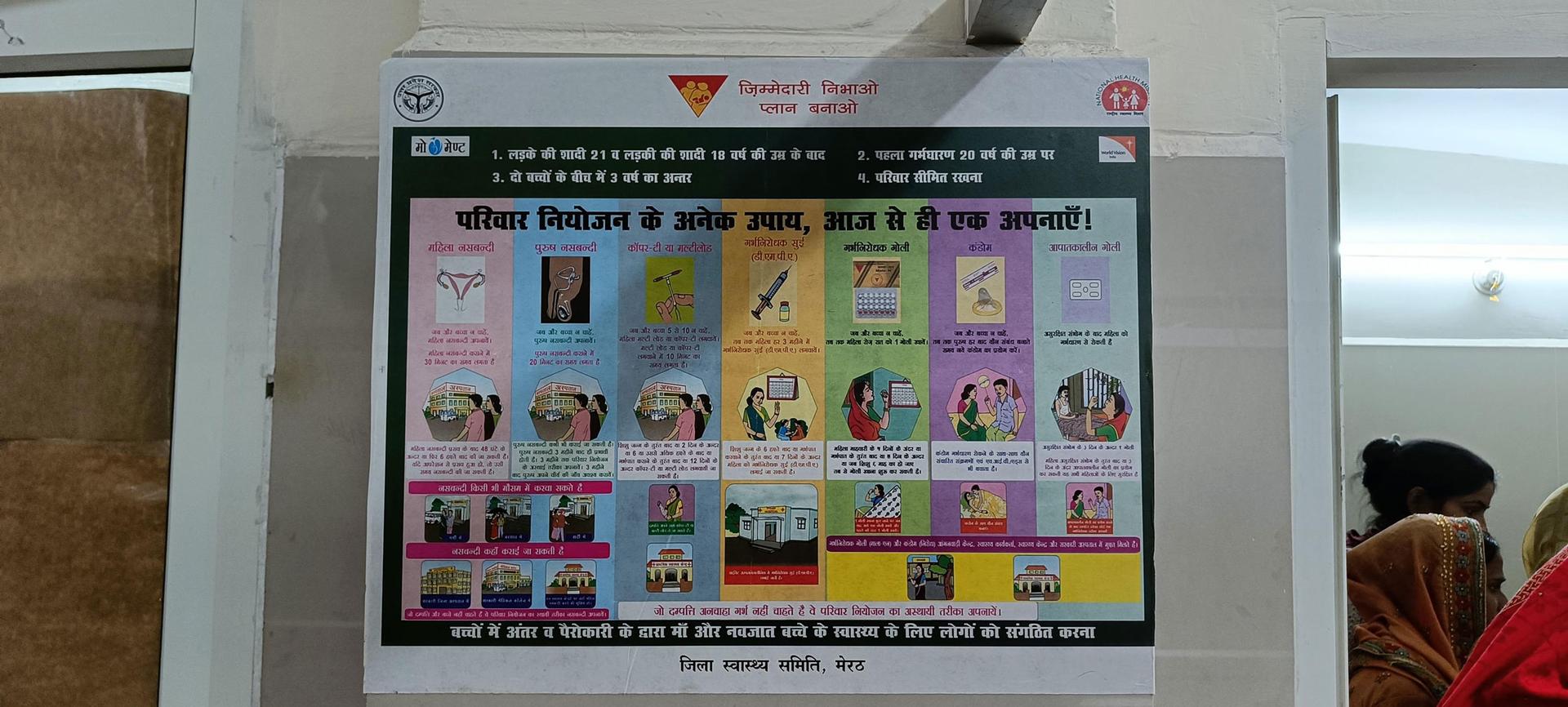

Among modern contraceptive methods, government data shows the rate of female sterilization is nearly 38% whereas male sterilization is a paltry 0.3%. In the coming years, Vajpeyi said India needs to do more to encourage men to take part in family planning, through targeted social and behavioral change communication campaigns.

Kuhika Seth, a social scientist who studies issues related to sexuality and reproduction, said that engaging men in family planning would be a game changer.

The shift has begun in small ways. Family planning awareness drives in rural areas, for example, used to be called mother-in-law and daughter-in-law meetups. Now, the sons are also a part of it.

Increased access to various types of birth control

India’s family planning program has relied heavily on one method of contraception — female sterilization, which is by far the most common method. Health workers and women preferred it because it was a one-time procedure that didn’t require any follow-ups.

But the method may not be appropriate for young couples who are increasingly delaying having children, said Andrea Wojnar, India representative at the United Nations Population Fund, adding that India’s youth needs reversible contraception methods.

“It’s really important for the government to make sure that there is a full range of family planning options,” Wojnar said. That includes temporary methods such as IUDs, contraceptive pills, injectables and condoms. Usage of these different methods has been increasing, albeit slowly.

Harnessing demographic advantages

India is home to the largest cohort of young people, with 52% of Indians below the age of 30. The country is currently enjoying this demographic advantage.

“Fortunately, for the coming several decades India will have [an] advantage, because India’s bulk of the population will be in the working-age group,” James said.

But leveraging this demographic advantage depends on a significant increase in the rate of women who participate in the workforce. Currently, only about 20% of Indian women above the age of 15 are employed — among the lowest for emerging economies — and has been in a gradual decline for several years. Gains in family planning mean that Indian women aren’t spending as many years in child rearing and the next step is to make sure they can get an education and have access to job opportunities, James said.

While India is a youthful country, its aging population is also growing. By 2050, India will have thrice as many people over the age of 60 as it does now.

“That will bring about challenges of greater investments needed for elderly care, pensions, housing assistance services,” Wojnar, with the UN, said.

Still, India’s growing population should be seen as an opportunity, she said.

“India has the upper hand. They have a very strong deck of cards to play in taking the population and the world forward,” Wojnar said.

“The thing to keep in mind is where women and girls have decision-making power, where they’re educated and where they’re able to exercise their reproductive rights and choices, this is where the country will succeed.”