Another rising cost of climate change: PG&E’s blackouts, now needed to prevent wildfires

A firefighter gives orders as he battles the Kincade fire in Windsor, California, Oct. 27, 2019.

With wildfires forcing evacuations in the Los Angeles hills and Sonoma County, and parts of California under an “extreme red flag warning” from the winds, the state’s largest electric utility triggered another preemptive blackout on Tuesday that left half a million customers in the dark.

Shutting down the power has become PG&E’s primary defense to keep its troubled power lines from sparking wildfires in the dry landscape, as happened in 2017 and 2018 to deadly effect.

It also vividly illustrates how the costs of failing to address climate change reach far wider than just property lost to the flames. The blackouts, while likely saving homes and lives, mean many businesses and industries can’t operate, schools can’t open, and gas stations remain shuttered. For small businesses, several days without power or customers could be devastating. Just the blackouts alone could cost the state billions.

“This is an example of the cost of not fixing climate change,” said Scott Denning, a climate scientist and professor of atmospheric sciences at Colorado State University. “People talk about the trillions of dollars it will cost to do something like the Green New Deal. But how many trillions does it cost when millions of people in the world’s fifth largest economy are stuck without power?”

One researcher estimated the costs from PG&E’s first blackout earlier this month at about $2.5 billion. Tuesday’s blackout was the utility’s third major outage this month, and with extreme winds projected to last several days, it could stretch for days.

Some economists and state policy makers are worried that chronic blackouts could drive business away from the state—and, ultimately, mean higher costs.

“PG&E is bankrupt because of the 2017 and 2018 fires. They don’t know what exactly the liabilities are, but they’re between 20 and 30 billion, and that’s just one utility and two seasons,” said Leah Stokes, a political science professor at the University of California Santa Barbara who specializes in public policy related to climate change. “If you think about how that would be multiplied across the economy, then we’re in the trillions of dollars, potentially, annually, for climate impacts. That’s a huge amount of money.”

How climate change fuels the flames

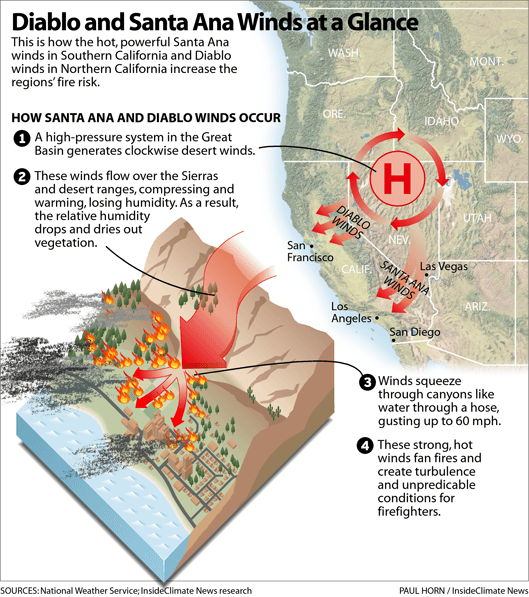

California has long been prone to fires in the fall, when seasonal winds stoke blazes in brush and forests parched from the summer. But climate change has made the state warmer and drier, providing more fuel for the fires while amplifying the dangers of a population spreading into forested areas and an aging, poorly maintained power infrastructure.

“This weekend was a confluence of both bad luck and long-term climate trends, plus those other issues,” said Daniel Swain a climate scientist at UCLA.

Swain remarked on the striking similarities between conditions surrounding the current fires and those in recent years, including the most destructive and deadly fires in the state’s history.

“This year, last year and the year before — heading into November, the rains were very late and allowed these windy conditions to coincide with the summer-like dryness of vegetation,” Swain said. “That’s where the climate signal is coming: The change in the precipitation and the background warming effect.”

The 10 most destructive fires in California history have all occurred since 1990 — seven of them in the last four years — and researchers project that wildfires will only get bigger and more destructive and frequent in a hotter, drier California. The state’s 2018 climate assessment says the area burned by wildfires could increase by nearly 80 percent by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions continue at a high rate.

Bankruptcy and years of maintenance failures

In the wake of a series of especially dangerous fire seasons, researchers and policy makers have frantically debated how to manage the risks. With millions of people sitting in darkened houses and shuttered businesses amid the latest blackouts, much of that debate centers on the gargantuan dilemma of providing the most populous US state with electricity while also keeping people out of harm’s way.

State investigators blame PG&E for 18 of the 170-plus wildfires that menaced Northern California in 2017, and for last year’s Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise and killed 85 people, making it the state’s worst fire on record.

The company, facing mounting liability claims, filed for bankruptcy in January. Months earlier, it announced it might impose preemptive blackouts during high-wind events to minimize the risk of power lines sparking fires. These preemptive efforts were intended to be occasional, but given the growing fire risks, they could become commonplace.

While the company has been widely criticized for failing to maintain its system over the decades, it has made an effort to ramp up its preventative measures, including cutting back trees near transmission lines, in recent years.

But work required to “fireproof the grid” is so extensive and costly, it could take years to complete. So the company has said it will reduce the short-term risks by cutting power to millions of people.

Though powerlines are responsible for a relatively small number of California fires, a higher proportion of those fires become destructive.

“There’s an especially high value in preventing those particular fires,” Swain said. “There are potential benefits from turning off the electricity. The problem is that, A) that’s not the only source of fires, and, B) there is a huge and growing list of negative consequences of turning the power off and using that as a blunt tool.”

“All of a sudden, it’s become a major crisis,” Swain said.

Solutions to the PG&E problem?

The situation has pushed the issue to the forefront of the state’s political and public policy debates. This summer, Gov. Gavin Newsom authorized a $21 billion fund to help utilities pay for claims linked to wildfires caused by their equipment.

“It’s a huge policy debate,” Stokes said. “This is front-of-mind for a lot of policy makers and the governor.”

One proposal is for public entities, like San Francisco, to buy PG&E, but like so many of the possible fixes, that would only go part of the way toward solving the problem.

“It’s not like there’s a simple solution here. Yes, PG&E should be doing more to maintain its systems and doing more proactive work, but even if it’s owned by the state, that’s not a magical solution,” Stokes said.

Among the possible solutions is a transition of the state’s power system from the current one, in which big utilities deliver and distribute the power, to a distributed system in which power is generated, controlled and distributed locally and across smaller grids, or microgrids. This would reduce the risk of sparking fires because these localized systems don’t require long-distance transmission lines.

The state passed a law last year to expand the development of microgrids, and these systems are gaining traction. But the vast majority of power will continue to come from the big utilities.

“If you’re a homeowner, you need to be able to deal with the fact that every fall your lights are going to go out,” Denning said. “If you’re PG&E, you have to consider cutting huge swathes of forest on either side of power lines so sparks don’t get into trees or spend a huge amount of money burying power lines.”

“In the long run, they have to get off fossil fuels because fossil fuels are causing the climate change that’s contributing to the fires,” Denning added. “On the other hand, there’s the immediate problem which is: What do you do this week when the state is on fire?”

This story was originally posted at InsideClimate News.

InsideClimate News is a Pulitzer Prize-winning non-profit, non-partisan news organization that provides essential reporting and analysis on climate, energy and the environment for the public and decision makers. ICN serves as a watchdog of government, industry and advocacy groups and holds them accountable for their policies and actions. Already one of the largest environmental newsrooms in the country, ICN is committed to establishing a permanent national reporting network, to training the next generation of journalists, and to strengthening the practice of environmental journalism.