Caste discrimination exists on college campuses. Some schools are trying to change that.

Jaspreet Mahal, a researcher at Brandeis. She is a Sikh, a member of a minority religion in India that does not recognize caste, but her husband, a doctoral student at University of Massachusetts in Boston, is a member of the Dalit community.

This article is part four of the “Caste in America” series. Read part one, part two and part three. This series was produced with funding from the Pulitzer Center and in partnership with WGBH.

A few weeks ago on the campus of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, near Boston, dozens of students poured out of classrooms just before noon.

Young women and men, in a rich mosaic of skin hues and colors, trudged through light snow to the cafeteria or their next class. As at other colleges across the country, these students are protected, at least on paper, from prejudices that seep in from off-campus. But they aren’t entirely — not when it comes to bias based on caste, the ancient religious and social hierarchy of Hindus that originated in India.

Jaspreet Mahal, a former graduate student who is now a researcher at Brandeis, has witnessed caste bias on campus firsthand. She is a Sikh, a member of a minority religion in India that does not recognize caste, but her husband, a doctoral student at University of Massachusetts in Boston, belongs to the Dalit community. Dalits, formerly known as “Untouchables,” rank the lowest in the Hindu hierarchy.

On several occasions in the company of upper caste Hindu students who knew little or nothing about her spouse, Mahal said they sometimes let slip their views on Dalits, often in insulting and derisive comments. She compared herself to a fly on the wall, listening in to deep-seated prejudices that few of them would dare express aloud among Indians outside their upper and dominant castes.

More: Read the whole “Caste in America” series

Mahal said what she calls “caste privilege” has come out in other ways on campus. During a graduate class discussion about social-economic development in India,she saida fellow student stood up to talk about the historical achievements of her caste.

“It seems harmless. But to South Asians in the room, they would be able to place her in a dominant caste position. … This was somebody showing their privilege, which silences others.”

“It seems harmless. But to South Asians in the room,they would be able to place her in a dominant caste position,” Mahal explained. “This was somebody showing their privilege, which silences others.”

Related: Even with a Harvard pedigree, caste follows ‘like a shadow’

Brandeis officials have been taking a close look at these kind of stories. The university, founded as an academic haven for Jewish students who faced anti-Semitism at other schools, has strict prohibitions against racism, gender inequality and homophobia, among other behaviors. Caste bias is not one of them. Soon Brandeis will become a rare American university to ban caste discrimination.

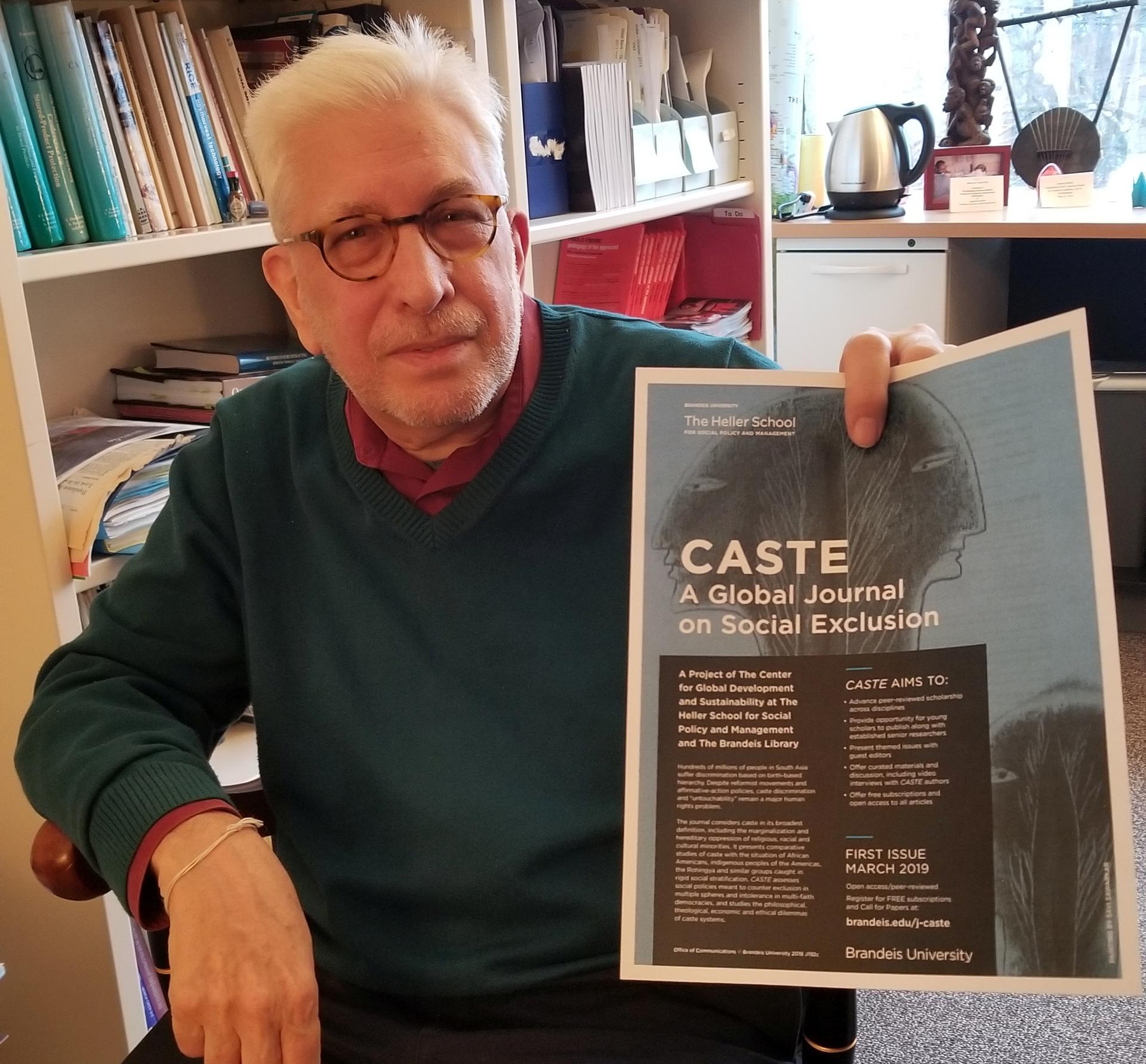

Leading the charge is Larry Simon, a professor at Brandeis’ Heller School of Social Policy and Management and an expert on caste.

“We have many students who come from low caste backgrounds and others who come from high caste and other backgrounds, including Dalits, and they bring sometimes a sense of privilege and sometimes a sense of being stigmatized to America, where caste is not a household word,” Simon said.

Caste-based discrimination often appears in higher education institutions, according to a report published last year by Equality Labs, a Dalit research organization. The report states that caste is “especially relevant in graduate schools due to the higher numbers of first and second-generation immigrants served.” Overall, students from India represent the second-largest group of international students in the US. But universities are just beginning to address caste dynamics among its student population.

In addition to Brandeis, Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley, are also exploring caste issues on their campsues.

There are about 2.5 million people of Indian descent living in America. About 60,000 live in Massachusetts, according to a survey conducted by the Boston Redevelopment Authority, a number dwarfed by Indian populations in California, New Jersey, New York and Texas. High caste and dominant caste Indians make up about 90 percent of the immigrant population, according to the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Advanced Study of India.

Invariably, caste comes up, saidRajkumar Kamble, a chemical engineer in Houston, who worked with Ambedkar International, a Dalit human rights organization named for social reformer B. R. Ambedkar. He recounted the story of a student who was initially accepted into a doctoral science program at the University of Alabama and then allegedly rejected by the lab’s director because of his caste.

“The professor was of Indian origin, and he wanted to check on the caste background of the student whom he was considering for admission, and the moment he came to know about his caste, he denied that student, who now has completed his studies and other things and has not decided to go to the court of law,” Kamble said in an interview before his death last August.

The legal challenges to caste bias in America

But even if the doctoral student had gone to a court of law, there are no legal precedents for such a lawsuit succeeding, said Kevin Brown, a professor at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law and an expert on caste.

“Unfortunately then, there are very little protections for Dalits in the United States for the discrimination that they encounter here with caste Hindus.”

“The United States doesn’t recognize the concept of caste, so it’s not included in any of our laws that prohibit discrimination,” Brown said. “We in the US just haven’t had as much experience with problems within the Indian communities that moved to the United States. So our legal system hasn’t caught up to that. Unfortunately then, there are very little protections for Dalits in the United States for the discrimination that they encounter here with caste Hindus.”

Related: The US isn’t safe from the trauma of caste bias

When caste has been addressed in US courts over the decades, it has been in the context of immigration. Some Dalits have sought asylum based on claims of political persecution. Rarely have these claims resulted in a grant of asylum, Brown said.

There was also a renowned Supreme Court case, the United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. The Indian Sikh man had identified himself as a “high caste Aryan, of full Indian blood” and asked to be declared white in order to get US citizenship. The justices unanimously decided that he was not and denied his petition in 1923. At the time, South Asians could not become citizens through naturalization, unless they were white.

Currently, caste as a 21st century legal issue is being tested in a New York case that has yet to reach the courts.

Shunned in the workplace

That case involves a restaurant called Sahib, in the Curry Hill section of Manhattan. A 2017 headline in a New York Times review proclaims that Sahib “Lets You Eat All Over India.” But civil rights advocates said the headline obscured the caste bias swirling around the restaurant. A Dalit waiter from Nepal, a predominantly Hindu country that borders India, alleged that year he was humiliated by the upper-caste managers and staff. The waiter is being represented by attorney Swati Sawant, who filed a complaint on behalf of the International Commission for Dalit Rights in Washington, DC, which has taken on the case. She requested WGBH News not use the waiter’s name.

“The manager and co-workers discriminated against him because he belongs to a lower caste,” said Sawant, who practices in New York City and Cambridge, Massachusetts. “They continuously remarked that he was an ‘Untouchable.’ They wouldn’t eat with him, you know. This case was denied by the New York State Division of Human Rights. The reason: because caste is not recognized” as an unlawful ground of discrimination.

Sawant has since taken the case to the New York office of the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.Sahib’s owner telephoned WGBH News from New Jersey to confirm that a complaint has been filed against the restaurant, and to say that he will wait for its decision before issuing a statement.

Dalit activists in the United States argue that another venue where caste bias occurs is Hindu advocacy organizations, the most prominent of which is the Hindu American Foundation in Washington, DC.

Suhag Shukla, the foundation’s co-founder and executive director, said that she is deeply offended by this charge. The HAF condemns discrimination across the board, she said, but suggested what some call casteism may be overblown.

“Where any sense of hierarchy and any sort of manifestation of caste that denies the human dignity, HAF firmly believes in the annihilation of those types of practices,” Shukla said. “But where some sort of caste tradition might give people a sense of solidarity or a way of relating to one another and is a force for good, I don’t know that those types of practices — that are also part of caste practices — should be annihilated.”

Read: Does America have a caste system?

Shukla appeared to be referring to the many associations for members of a particular caste. Those groups maintain they promote a sense of community and the preservation of culture.

More broadly, the survey conducted last year by Equality Labs,found that two out of three so-called “Untouchables” reported being treated unfairly at their workplace, and two out of five Dalit students reported being discriminated against in schools, from kindergarten through college. It is the only survey of its kind ever done.

About 1,200 people descended from the Indian subcontinent responded to the online survey. They were not drawn from a random sample. Upper caste critics have cited how the survey was done in questioning its findings.

Thenmozhi Soundararajan, executive director of Equality Labs,told WGBH News that as more and more Dalits in the country open up about their caste identities, she expects to hear more stories about discrimination. Soundararajan predicted more legal protections will follow.

“… they’re so threatened by a report like this, because it finally gives caste-oppressed people a piece of data that can be used to help protect them where there’s been no protections before.”

“Unfortunately for people who have caste privilege, we have laws against discrimination in the United States,” Soundararajan said. “And that’s why I think that they’re so threatened by a report like this, because it finally gives caste-oppressed people a piece of data that can be used to help protect them where there’s been no protections before.”

One university’s example

Some see a reliance on US law to insulate Dalits and low caste Indians from caste bias as wishful thinking, given the absence of constitutional and statutory protections. But Brandeis officials said they will provide such safeguards based on other precedents.

Mark Brimhall-Vargas, chief diversity officer and vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion at Brandeis, said the school plans to deal with caste bias head-on.

Related: Love conquers caste for this couple, but Indian marriage traditions continue in US

“When a university has a non-discrimination policy, obviously it will contain protected categories of identity that are prohibited from discrimination based on federal or state law,” Brimhall-Vargas said. “But there are other categories of identity that are prohibited based only on the will of the campus, that in this campus community we shall not discriminate against certain people. In that sense, caste does not receive currently federal, or to my knowledge, any state-level protections. We’re not afraid to be leaders at Brandeis.”

A campus committee that includes Brimhall-Vargas, Mahal and Simon has recommended Brandeis ban caste bias and discrimination, a proposal legal counsel is reviewing. Final approval from Brandeis President Ronald D. Liebowitz is pending.

This fall, Brandeis is expected to become the first major university in America to adopt such a campus ban.

Follow the “Caste in America” series.