In New York, volunteers engage in a quiet form of advocacy for immigrants facing deportation

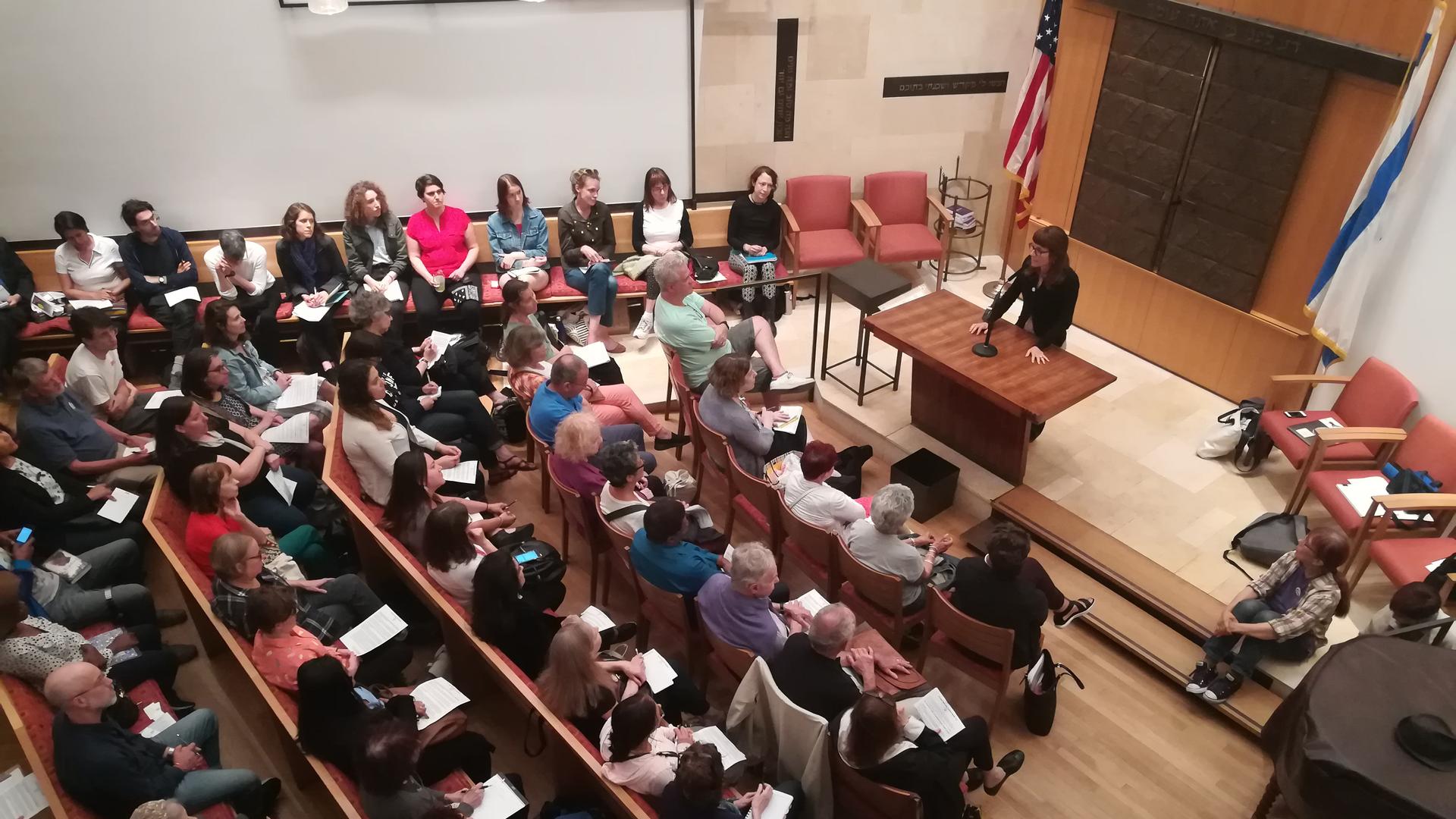

Sara Gozalo, supervising organizer with the New Sanctuary Coalition, teaches an accompaniment training at East End Temple, Manhattan, on June 27, 2018.

While New Yorkers were organizing a weekend protest across the Brooklyn Bridge against family separations at the southern border, about 160 congregants of East End Temple in Gramercy Park, Lower Manhattan, gathered on Wednesday, June 27, to hear about a different style of activism.

Organizers of the New Sanctuary Coalition, the local branch of a national interfaith alliance that opposes detentions and deportations, were invited by Rabbi Joshua Stanton and district Assemblyman Harvey Epstein to present their “accompaniment program.” The initiative trains volunteers to do a very simple thing: Walk with immigrants to their check-ins and court dates, and wait for them until their appointments are over.

“When we say we do advocacy without confrontation, we mean without confrontation,” Sara Gozalo told the audience. “But believe me, your presence there, in a place accustomed to doing everything they do in the shadows, makes a huge difference.”

The coalition made headlines in January when Ravi Ragbir, its leader, managed to avoid his own deportation with the support of the community.

More about Ravi Ragbir: ‘The fear of living as a fugitive is very high’

The coalition allowed PRI to document the hour-long introduction, but not the specific strategies covered in rest of the training. The volunteers packed the synagogue. Several families brought their children in strollers.

“Everything that’s going on in our country right now has just been extremely upsetting,“ said Aviva Lazar, 41, a congregant. “I’m really moved by how many people are here.”

Philip Gollance, a soft-spoken 63-year-old actuary who is part of the temple’s social justice committee, said he too wants to join the action.

“A lot of our activity, recently, has been about immigrant rights and the threats to them,” he said. “It’s very concerning to me. So, if I can do a little bit to help, I want to.”

The East End Temple is not a partner of the New Sanctuary Coalition, but the congregation has members who are not US citizens. The Jewish tradition, said Stanton, is about both learning and action. “This is the action side,” he said.

Gozalo asked the group which the words they associate with “immigrant.” The first replies were “victims,” “poor,” “isolated” and “depressed.”

“That’s it? Come on, don’t you watch Fox News?” she replied, eliciting a laughter.

The second round of attributes had a sharper edge: “Criminals,” “illegal,” “usurpers” and “stupid.” Gozalo nodded. Those were the words that immigrants served by the coalition are used to hearing, she said.

She asked attendees if they know how immigrants apply for asylum (it’s a complex process), what ICE is (the federal immigration agency, Immigration and Customs Enforcement), and where ICE arrests undocumented people. “Basically everywhere,” she said, including at their homes, workplaces, restaurants, schools, hospitals and courthouses.

In 2017, ICE made 144 courthouse arrests in New York, compared to just 11 in 2016, according to data released by the Immigrant Defense Project, an advocacy group that is fighting deportations. In June, members of the New York state assembly introduced legislation to prevent ICE from arresting immigrants at courthouses without judicial warrants or court orders. ICE argues that using courts, after people have been screened for security, is a safer way to make arrests.

More: Should immigration agents be allowed to wait around courts to detain people?

The reality of immigration enforcement paralyzes immigrants, said Gozalo.

“Except for our friendship, they live with this fear every day, and everywhere they go,” she said. “That’s why you are here today.”

The accompaniment program was launched in 2007, the same year the coalition was established. Founding members, including Ravi Ragbir and Jean Montrevil, began to reach out to their neighbors to support them in their own immigration check-ins. Montrevil was deported to his native Haiti at the beginning of this year.

“Every ICE check-in now is very high-risk,” Gozalo told PRI after her presentation. “And so every check-in that we do, we prepare for the worst.”

The coalition organizes about 25 accompaniments each week, though last week they accompanied 35 immigrants to court hearings and ICE check-ins. Before Donald Trump took office, she says, they only arranged three or four accompaniments per week. Each immigrant is usually escorted by five or six volunteers from a pool of about 650 people. But hundreds more volunteers have been attending an increasing number of trainings.

Joan Racho-Jensen, who said she is over 50, and Linda Chavez, 53, are two volunteer leaders who have been part of the movement for more than a year. Last month, Chavez also joined the coalition’s staff as an organizer.

“It is a historic moment for the accompaniment,” said Gozalo. “So many people are participating. We are pushing the boundaries of the immigration system.”

The New Sanctuary Coalition is growing along with immigration enforcement. ICE arrests for the New York City area went up 39 percent to 2,576 people in the 2017 fiscal year compared to 2016, according to the Pew Research Center.

Epstein, a longtime supporter of Ragbir and his organization, called the last year and a half “horrible.” East End Temple is in his district and while he said the city and the state are moving in the right direction to protect non-citizens and offer legal representation, “we’re not doing a good enough job today.”

Participating in the accompaniment program comes with strict rules. Gozalo trained the volunteers to observe but not advise immigrants, whom they should refer to as their “friends.” She also said they should not interfere in any way or ask questions to immigration officers.

Volunteers must show respect to everyone they encounter, from building guards to ICE agents and judges at both 26 Federal Plaza and the Varick Street Courthouse where New York City’s immigration facilities are located. They also should not judge immigrants, even those who have criminal convictions.

“We will stand in solidarity, because we recognize that our criminal system is racist and unjust, and because we believe in forgiveness and compassion,” she instructed the group. “Are there any questions about that?”

An elderly man asked if volunteers could be arrested.

“Not if you behave yourself,” said Gozalo, laughing. “You’re not doing anything wrong. You’re not doing anything illegal.”

No one has been arrested for accompanying immigrants to their appointments in their 11 years of running the program. For some immigrants though, said Gozalo, it will be the first time they’ll feel the support of the community.

And that power is real, she said. The movement has heard of cases where judges acknowledge the community ties of an immigrant and grant bond instead of detention, or ICE agents delay deportations while cases continue.

ICE has detained three of the hundreds of immigrants they have accompanied since January 2017, while four others avoided deportation by moving into houses of worship, where ICE will not conduct arrests.

ICE in the past has not responded to requests for comment about the accompaniment program and did not immediately respond to PRI’s questions for this report.

But there are challenges. Accompaniments can be tough on volunteers, said Gozalo, particularly when their “friends” are detained. She regularly talks with them about what they witness, and as a tight community they also talk, they drink together, they share experiences.

Gozalo also told the volunteers that confronting an immigration official, being vocal during an accompaniment could harm the immigration cases of those they are trying to help.

Some of those participating in the training said they were considering the direction of their advocacy for immigrants’ rights outside the accompaniment program.

Lazar says that, as a single mother, she couldn’t take any action that would risk her own arrest. But Chavez, a US citizen, says she has the privilege to engage in civil disobedience, types of protest that could lead to arrest. “That’s something that I have considered,” she said.

For Racho-Jensen, being part of the accompaniment program has given her a new perspective.

“It used to be, ‘I’ll just go on the street and get arrested.’ But now I choose very carefully where I do that,” she said.